It was August 13, 1945, and the 'demon core' was poised, waiting to be unleashed onto a stunned Japan still reeling in fresh chaos from the deadliest attacks anyone had ever seen.

A week earlier, 'Little Boy' had detonated over Hiroshima, followed swiftly by 'Fat Man' in Nagasaki.

These were the first and only nuclear bombs ever used in warfare, claiming as many as 200,000 lives – and if things had turned out a little differently, a third deadly strike would have followed in their hellish wake.

But history had other plans.

After Nagasaki proved Hiroshima was no fluke, Japan promptly surrendered on August 15, with Japanese radio broadcasting a recorded speech of Emperor Hirohito conceding to the Allies' demands.

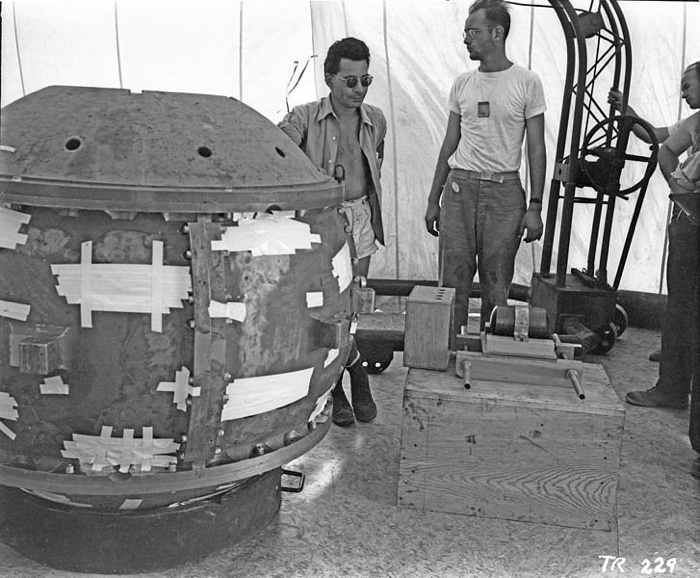

Recreation of 1945 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Recreation of 1945 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

As it turns out, this was the first time the Japanese public at large had ever heard one of their emperors' voices, but for scientists at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico – aka Project Y – the event had a more pressing significance.

It meant the functional heart of the third atom bomb they'd been working on – a 6.2-kilogram (13.7 pound) sphere of refined plutonium and gallium – wouldn't be needed for the war effort after all.

If the conflict had still been raging, as it had for almost five straight years, this plutonium core would have been fitted into a second Fat Man assembly and detonated above another unsuspecting Japanese city just four days later.

As it was, fate issued those souls a reprieve, and the Los Alamos device – code-named 'Rufus' at this point – would be retained at the facility for further testing.

It was during these tests that the leftover nuke, which ultimately became known as the demon core, earned that name.

Daghlian's burnt, blistered hand. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Daghlian's burnt, blistered hand. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

The first accident happened less than a week after Japan's surrender, and only two days after the date of the demon core's canceled bombing run.

That mission may have never launched, but the demon core, stranded at Los Alamos, still found an opportunity to kill.

The Los Alamos scientists knew well the risks of what they were doing when they conducted criticality experiments with it – a means of measuring the threshold at which the plutonium would become supercritical, the point where a nuclear chain reaction would unleash a blast of deadly radiation.

The trick performed by scientists in the Manhattan Project – of which the Los Alamos Lab was a part – was finding just how far you could go before that dangerous reaction was triggered.

They even had an informal nickname for the high-risk experiments, one which hinted at the perils of what they did. They called it "tickling the dragon's tail", knowing that if they had the misfortune to rouse the angry beast, they would be burned.

Louis Slotin, left, with the first nuclear bomb assembly, Gadget (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Louis Slotin, left, with the first nuclear bomb assembly, Gadget (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

And that's exactly what happened to Los Alamos physicist Harry Daghlian.

On the night of August 21, 1945, Daghlian returned to the lab after dinner, to tickle the dragon's tail alone – with no other scientists (just a security guard) around, which was a breach of safety protocols.

As Daghlian worked, he surrounded the plutonium sphere with bricks made of tungsten carbide, which reflected neutrons shed by the core back at it, edging it closer to criticality.

Brick by brick, Daghlian built up these reflective walls around the core, until his neutron-monitoring equipment indicated the plutonium was about to go supercritical if he placed any more.

He moved to pull one of the bricks away, but in doing so accidentally dropped it directly onto the top of the sphere, inducing supercriticality and generating a glow of blue light and a wave of heat.

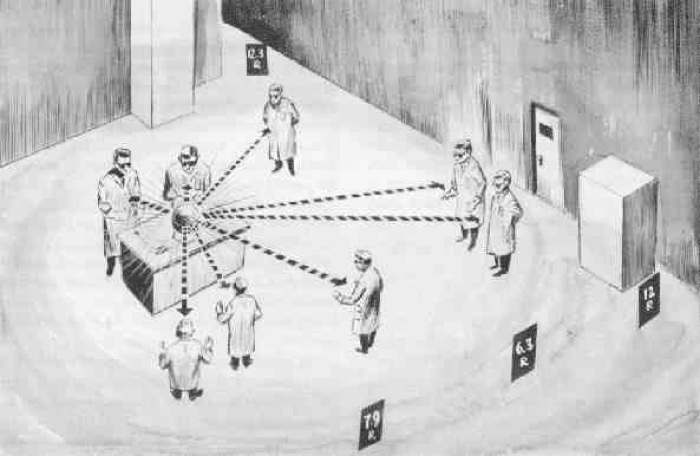

Recreation of 1946 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Recreation of 1946 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Daghlian reached out immediately and removed the brick, noticing a tingling sensation in his hand as he did so.

Unfortunately, it was already too late.

In that brief instant, he had received a lethal dose of radiation. His burnt, irradiated hand blistered over, and he eventually fell into a coma after weeks of nausea and pain.

He was dead just 25 days after the accident. The security guard on duty also received a non-lethal dose of radiation.

But the demon core was not yet finished.

Despite a review of safety procedures after Daghlian's death, any changes made weren't enough to prevent a similar accident occurring the following year.

Recreation of 1946 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Recreation of 1946 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

On May 21, 1946, one of Daghlian's colleagues, physicist Louis Slotin, was demonstrating a similar criticality experiment, lowering a beryllium dome over the core.

Like the tungsten carbide bricks before it, the beryllium dome reflected neutrons back at the core, pushing it toward criticality. Slotin was careful to ensure the dome – called a tamper – never completely covered the core, using a screwdriver to maintain a small gap, acting as a crucial valve to enable enough of the neutrons to escape.

The method worked, until it didn't.

The screwdriver slipped and the dome dropped, for an instant fully covering the demon core in a beryllium bubble bouncing too many neutrons back at it.

Another scientist in the room, Raemer Schreiber, turned around at the sound of the dome dropping, feeling heat and seeing a blue flash as the demon core went supercritical for the second time in the space of a year.

Diagram of the 1946 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Diagram of the 1946 accident. (Los Alamos National Laboratory)

"The blue flash was clearly visible in the room although it (the room) was well illuminated from the windows and possibly the overhead lights," Schreiber later wrote in a report.

"The total duration of the flash could not have been more than a few tenths of a second. Slotin reacted very quickly in flipping the tamper piece off."

Slotin may have been quick in rectifying his deadly mistake, but again, the damage was already done.

He, and seven others in the room – including a photographer and a security guard – were all exposed to a burst of radiation, although Slotin was the only one to receive a lethal dose, and a greater one than that inflicted on Daghlian.

After an initial bout of nausea and vomiting, he at first seemed to recover in hospital, but within days was losing weight, experiencing abdominal pain, and began showing signs of mental confusion.

Operation Crossroads. (US Department of Defence)

Operation Crossroads. (US Department of Defence)

A press release issued by Los Alamos at the time described his condition as "three-dimensional sunburn".

Nine days after the screwdriver slipped, he was gone.

The two deadly accidents, only months apart, finally saw real changes take place at Los Alamos.

New protocols meant an end to 'hands on' criticality experiments, with scientists forced to use remote control machinery to manipulate radioactive cores at a distance of hundreds of meters.

They also stopped calling the plutonium core 'Rufus'. From then on, it was known only as the 'demon core'.

But after everything that had happened, the leftover nuke's time was up too.

Following the Slotin accident – and the core's resultant increase in radiation levels – plans to use it in Operation Crossroads, the first post-war nuclear explosion demonstrations to commence at the Bikini Atoll a month later, were shelved.

Instead, the plutonium was melted down and reintegrated into the US nuclear stockpile, to be recast into other cores as necessary. For the second and last time, the demon core was denied its detonation.

While the deaths of two scientists can't be compared to the untold horrors if the demon core had been used in a third nuclear attack against Japan, it's also easy to understand why the scientists gave it the superstitious name they did.

Then there are the weird details that fill in the backdrop of the story.

Like how Daghlian and Slotin weren't just killed by similar accidents involving the same plutonium core: both incidents took place on Tuesdays, on the 21st day of the month, and the men even passed away in the same hospital room.

Of course, those are just coincidences. The demon core wasn't actually demonic. If there's an evil presence here, it's not the core, but the fact that humans rushed to make these terrible weapons in the first place.

And the real horror – besides the horrible effects of radiation poisoning – is how spectacularly mid–20th century scientists failed to protect themselves from the extreme dangers they were toying with, despite fully knowing the grave risks in their midst.

According to Schreiber, Slotin's first words immediately after the screwdriver incident were simple, and already resigned.

He had comforted his dying friend Daghlian in hospital, and he knew what came next.

"Well," he said, "that does it."

A version of this post was first published in 2018.