Feeding a global population of 10 billion - the overwhelming number we're predicted to hit by 2050 - will be extremely difficult, but scientists say it is not impossible.

A radical new diet has the potential to improve public health, save countless lives, and protect our planet for future generations, according to a huge group of researchers.

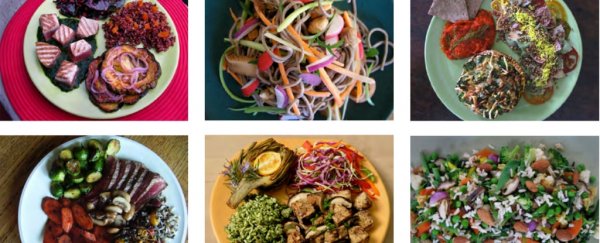

It all hinges on whether humans can ditch the daily dose of animal products and switch to a more flexitarian meal plan - one that is based largely on plants with modest amounts of fish, meat and dairy.

When more than three dozen international scientists come together to offer the world advice, it's usually time to sit up and listen.

As the world's population continues to grow, experts have been warning for years that a radical transformation of the global food system is urgently needed. Otherwise, we might never meet the Paris climate agreement or the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals.

"Global food production threatens climate stability and ecosystem resilience," writes Johan Rockström, a researcher in climate impacts at Stockholm Resilience Centre.

"It constitutes the single largest driver of environmental degradation and transgression of planetary boundaries. Taken together the outcome is dire."

Bringing together lead scientists from around the world, the EAT-Lancet Commission has now developed what it calls "the planetary health diet".

(Lancet)

(Lancet)

The good news is that very little food that you eat now is off-limits. Instead, it's all about moderation. For instance, you can still enjoy a slab of juicy red meat, but only once a month or so. On the other hand, fish and chicken are more of a once-every-few-days affair.

The rest of the time, the authors argue that nuts and legumes should take up your protein needs.

"Transformation to healthy diets by 2050 will require substantial dietary shifts," writes one of the researchers, Walter Willett, an expert in epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard University.

"Global consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes will have to double, and consumption of foods such as red meat and sugar will have to be reduced by more than 50 percent."

(The Lancet)

(The Lancet)

Meeting these ambitious targets will not be easy. Not only will it require a more flexible diet, it will also demand dramatic reductions in food losses and waste, and major improvements in food production practices.

If we are to believe the Commission's research, however, the revolutionary changes will be worth it. Drawing on dozens of studies, the authors predict that increased consumption of plant-based diets could reduce emissions by 80 percent come 2050.

Not only will these changes safeguard our shared environment, the authors estimate they will prevent approximately 11 million deaths per year, which represents nearly a quarter of all deaths among adults.

Naturally, there has been some push back since the report was released. The main rebuttals are mostly about the benefits to public health, and some are arguing that the report failed to provide enough scientific evidence that plant-based diets are better for a person's nutrition.

The authors, however, argue that the data they used - based on dozens of randomised controlled feeding studies - is both sufficient and strong enough to warrant immediate action.

If the Commission simply wanted to protect the environment, without a care for public health, the authors say they would have insisted on a vegan or vegetarian diet. The flexitarian diet was essentially their way of compromising our need for climate action with sustained public health.

The targets are certainly ambitious, but the authors say they are both possible and necessary.

This study has been published in The Lancet.