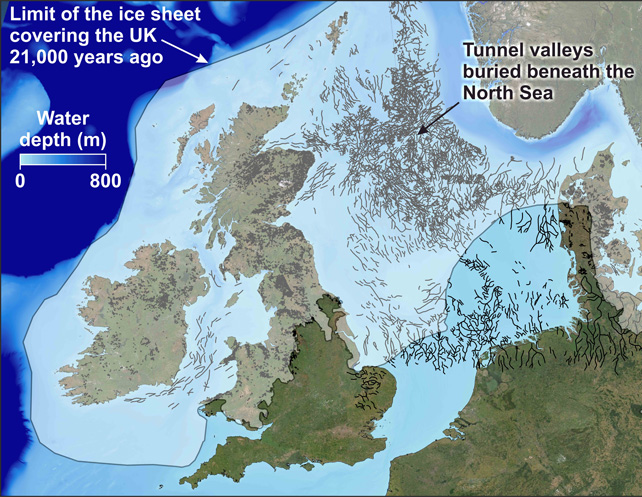

Hidden valleys buried beneath the ocean bottom in the North Sea were rapidly carved out during the "death throes" of an ancient ice sheet toward the end of the last ice age around 20,000 years ago, a new study shows.

The surprising subterranean structures could yield clues as to how modern ice sheets will react to rapid warming caused by climate change, researchers say.

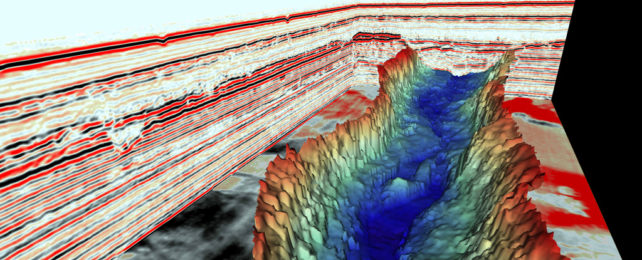

The buried structures, known as tunnel valleys, are massive underground ravines that were etched into the ancient seafloor by meltwater that drained into channels underneath the ice sheets.

The immense weight of the rapidly melting slabs of ice forced the flowing water to cut deep canyons into the seafloor; those channels have since been covered by hundreds of meters of sediment buildup.

Tunnel valleys can measure up to 93 miles (150 kilometers) long, 3.7 miles (6 km) wide, and 1,640 feet (500 meters) deep, according to a statement by researchers.

In 2021, researchers from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) mapped out the network of tunnel valleys in the North Sea, which was once covered by a massive ice sheet that also capped parts of continental Europe and the UK during the last ice age, between 126,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Using 3D seismic reflection technology, which emits sound waves to scan for structures beneath the seafloor, the team uncovered thousands of the buried canyons, some of which date back around 2 million years. These results were published in September 2021 in the journal Geology.

In the new study, which was published Oct. 5 in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews, the same researchers used the canyon maps, combined with computer models, to determine exactly how some of the tunnel valleys were birthed.

The results showed that the tunnels were likely carved out over the span of a few centuries, which is much faster than the team had initially anticipated.

Related: Discovery of 'hidden world' under Antarctic ice has scientists 'jumping for joy'

"This is an exciting discovery. We know that these spectacular valleys are carved out during the death throes of ice sheets," study lead author James Kirkham, a doctoral candidate with BAS, said in the statement.

"We have learned that tunnel valleys can be eroded rapidly beneath ice sheets experiencing extreme warmth."

Scientists have known about similar tunnel valleys for decades, but until now, the creation of these channels has been shrouded in mystery.

"We have been observing these huge meltwater channels from areas covered by ice sheets in the past for more than a century, but we did not really understand how they formed," study co-author Kelly Hogan, a marine geophysicist with BAS, said in the statement.

Tunnel valleys form when meltwater drains through vertical cracks in the ice into a meltwater river below the ice sheet, which channels liquid like a massive "plumbing system," researchers wrote in the paper.

As a result, valley formation is highly seasonal, with increased summer melting leading to more meltwater that temporarily accelerates the valley's growth.

Although the tunnel valleys form toward the end of an ice sheet's life, the study authors suspect that this drainage system could actually reduce the rate at which ice melts away and, in fact, may have prolonged the life span of the ancient North Sea ice sheet.

This hypothesis proposes that, by draining meltwater away from the ice sheets, the channels stopped liquid from pooling on top of or below the ice and thereby prevented more ice from melting.

However, the researchers are uncertain about how quickly the ice sheet was melting at that stage. Some tunnel valleys showed evidence of limited ice movement, suggesting that the valleys were slowing down the rate of ice loss.

But others showed evidence of rapid ice retreat, which could mean that the valleys were actually having the opposite effect of increasing the ice loss rate, according to the statement.

Scientists will therefore continue to study the tunnel valleys to see if they can get to the bottom of how meltwater channels may affect ice loss rates.

"The crucial question now is, will this extra meltwater flow in channels cause our ice sheets to flow more quickly, or more slowly, into the sea?" Hogan said.

Answering this question could be critical for accurately predicting how modern ice sheets, like those in Antarctica and Greenland, will be affected by climate change, the researchers said.

Current models that predict the rate of ice loss in these regions do not take into account tunnel valleys, which means researchers are missing a vital piece of the puzzle.

If new tunnel valleys start forming, or "switch on," below modern ice sheets (assuming they haven't already), it could drastically change how fast ice sheets melt, particularly because these structures take only take a few hundred years to form, the researchers wrote.

"The pace at which these giant channels can form means that they are an important, yet currently ignored, mechanism," Kirkham said.

Related content:

- 'Giant MRI of Antarctica' reveals 'fossil seawater' under ice sheet

- 'Doomsday Glacier' is teetering even closer to disaster than scientists thought, new seafloor map shows

- Never-before-seen microbes locked in glacier ice could spark a wave of new pandemics if released

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.