A retired cosmological theory should be given a second chance at explaining anomalies in our Universe, according to theoretical physicist Rajendra Gupta from the University of Ottawa in Canada.

By marrying the existing expanding Universe theory with a fringe explanation called the tired light hypothesis, Gupta has found the Big Bang could have taken place an astonishing 26.7 billion years ago. That's twice as old as current models predict.

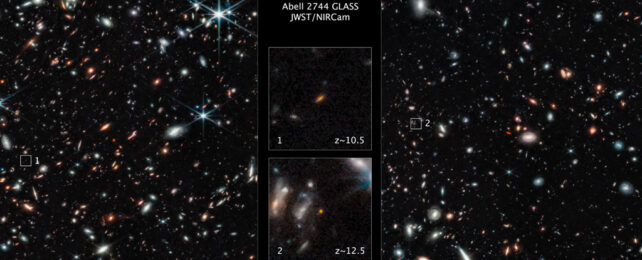

Those added years could explain why the most distant galaxies observed look surprisingly mature for star-cities that ought to have only been around for half a billion years.

Estimating the age of the Universe isn't unlike guessing a child's birthday based on their height. Objects in the distance – in every direction – look a little redder than their signature patterns of light might have us expect. The most likely explanation is that space expands, stretching those light waves apart like a pulled spring.

As light takes time to travel, redder light is older light, having been pulled over a greater distance. Working backward on this estimated growth rate, it's possible to use expansion to determine when the Universe was a compact volume seething with concentrated energy.

However, this hasn't been the only attempt to explain why light in the distance looks redder. In 1929, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky suggested light simply lost its puff over such vast stretches of space. Less energy means lower frequency and longer wavelengths, shifting the spectrum of bright, distant objects.

Basically, the light got 'tired'.

While Zwicky would later land upon a landmark discovery establishing the great mystery of dark matter, his tired light hypothesis suffered too many problems to make the grade, leaving the expanding Universe model as the theory of choice.

As Gupta puts it in his recently published proposal, that doesn't mean the two concepts are mutually exclusive. A combination might even help resolve why the earliest quasars and galaxies appear to be billions of years old.

It might also help explain why they look smaller than expected despite their well-developed masses.

Gupta's hybrid hypothesis presumes the Universe really is as big as we believe, having expanded to its size from a Big Bang event in the past. He starts with two expanding Universe models: one based on standard assumptions about the evenness and flatness of the cosmos and a second one that introduces some tweaks involving what's known as a coupling constant.

Coupling constants describe interactions of forces between particles, such as the way the electromagnetic fields of two protons held in close proximity will affect each other's behavior in specific ways.

All forces have a coupling constant, which isn't necessarily constant at all, changing with energy. This leaves room for coupling constants to vary enough to affect how light behaves. If this constant has changed over time, our calculations on the age of the Universe could be out by a significant amount.

"Our newly-devised model stretches the galaxy formation time by several billion years, making the universe 26.7 billion years old, and not 13.7 as previously estimated," says Gupta.

One of the problems with tired light theory is that a loss of energy in a light wave would correspond with a loss of momentum, affecting the appearance of far distant objects. With ancient galaxies looking unusually petite, this conflict might actually be a reason to reconsider the hypothesis.

As happens whenever observations don't quite align with expectations, scientists throw every idea they can think of at the problem to see what sticks. Some are mundane, some quirky, and some dig up the corpses of dead hypotheses to see if they have heartbeats after all.

Whichever explanation is left standing in the end, it will almost certainly change how we look at the way our Universe and its dazzling contents evolve over time.

This research was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.