The heart of every major galaxy is thought to contain a supermassive black hole – a place where gravity is so strong that anything, including light, gets devoured.

Like all black holes, supermassive ones form when stars collapse in on themselves at the end of their life cycles. On average, they're millions of times more massive than the Sun.

For years, scientists have struggled to capture a black hole on camera, since the absence of light renders them nearly impossible to see.

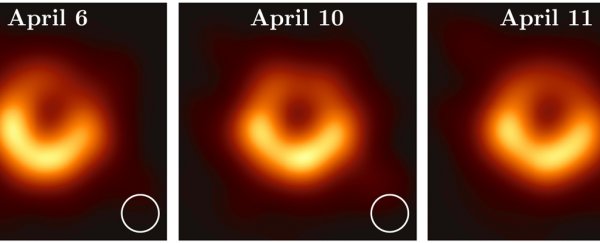

But on April 10, a group of scientists from the international Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration released the first-ever photograph of a supermassive black hole to the public. Though the image was fuzzy, it signified a major milestone for space research.

The accomplishment has now earned the team a 2020 Breakthrough Prize, which was awarded on September 5. The prize was started eight years ago by a team of investors including Sergey Brin and Mark Zuckerberg, and is often referred to as the "Oscars of Science".

The Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (EHT) team will collectively receive US$3 million, but the money will be divided equally among the group's 347 scientists, giving each person around US$8,600.

The award winning image. (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

The award winning image. (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

What the black hole photograph shows

The April image captured a supermassive black hole at the centre of the Messier 87 galaxy, which is about 54 million light-years away from Earth. The black hole in the photo likely had a mass equivalent to 6.5 billion Suns.

Black holes are defined by a border called the event horizon: a region of space so dense with matter that not even light can escape its gravity. This creates a circular 'shadow', where all light and matter is gobbled up.

Outside the event horizon, supermassive black holes have an accretion disk – clouds of hot gas and dust trapped in orbit. Though scientists can't see beyond a black hole's event horizon, they can detect the gas and dust in that disk, since the material gives off radio waves that can be captured by a high-powered telescope.

This is what EHT scientists captured in their groundbreaking image.

"As a cloud of gas gets closer to the black hole, they speed up and heat up," Josephine Peters, an astrophysicist at the University of Oxford, told Business Insider in October.

"It glows brighter the faster and hotter it gets. Eventually, the gas cloud gets close enough that the pull of the black hole stretches it into a thin arc."

Key features of a black hole. (ESO/ESA/Hubble/M. Kornmesser/Business Insider)

Key features of a black hole. (ESO/ESA/Hubble/M. Kornmesser/Business Insider)

To capture the image, researchers relied on 8 telescopes

The EHT scientists are stationed all over the world, at 60 institutions across 20 countries.

To capture the photograph, they relied on eight radio telescopes, operating in Antarctica, Chile, Mexico, Hawaii, Arizona, and Spain. They used a network of atomic clocks – extremely precise time-keeping devices that can measure billionths of a second – to sync up the telescopes around the world.

The EHT project began collecting information about black holes in 2006.

The image released in April was the result of observations that started two years prior.

(Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

(Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

"It feels like looking at the gates of hell, at the end of space and time," Heino Falcke, an Event Horizon Telescope collaborator, said when the photo was published in April.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: