You'd be forgiven if you haven't heard of von Economo neurons (VENs) or spindle neurons, a rare type of human brain cell. But these cells are now at the centre of an exciting scientific development: researchers have recorded their electrical activity for the first time.

The discovery was made possible due to a delicate and demanding analysis carried out on brain cells donated to science by a Seattle woman in her 60s, who agreed to donate tissue removed during surgery on a brain tumour.

Unlike many other types of neurons, VENs aren't found in rodent lab animals such as mice and rats; they're even difficult to find in human brains, which means studying these elusive cells is a serious challenge.

"At this point we're really in the descriptive phase of understanding these neurons," says neurobiologist Ed Lein, from the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Washington. "There are still many remaining mysteries."

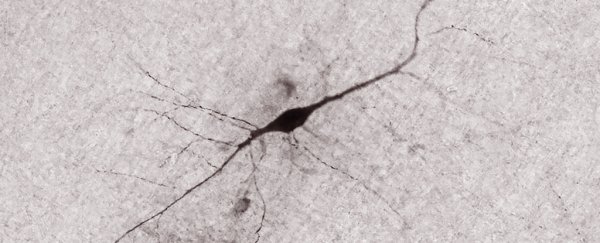

VENs are large and spindle-shaped (hence their alternative name), and are found in just three small regions of the brain. They also show up in great apes, whales, dolphins, cows and elephants, suggesting their presence could have something to do with being a social animal, or an animal with a larger brain in general.

People who get older without suffering the usual memory loss have been noted to have more VENs than normal; on the flip side, certain brain diseases seem to be associated with a loss of these types of neurons.

All of these factors have made VENs an intriguing subject for study - if only we could get a closer look at them more regularly.

In this case, the researchers had to hunt through thin slices of brain tissue to find the right neurons, and then carefully puncture them without breaking the outer membrane of the cells – an operation that allows electrical signals to then be captured. It wasn't easy.

"I would go to touch the cells with the pipette, and they would just explode," says neuroscientist Brian Kalmbach, from the Allen Institute. "It was super frustrating."

"But luckily, we were finally able to record from some of the cells, which was really exciting since that hadn't been done before."

The team measured electrical signals from three VENs, finding that there are differences compared with the signals from other types of neurons – it's not clear yet what those differences mean, but the measurements will get us closer to fully understanding these mysterious brain cells.

The team also analysed the gene expression patterns of VENs, discovering that they closely resembled a subset of cells called pyramidal neurons, as well as fork cells.

"It is clear that VENs, fork cells and a subset of pyramidal cells are transcriptomically similar to one another," the researchers write in their paper.

Getting a closer look at VENs is a highly important step, as researchers point out these neurons seem to be vulnerable to some neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases, but we have no idea why. The new study doesn't give us specific answers, but it's gotten us closer - and it was all made possible through a brain tissue donation.

"We're all keenly aware that the tissues we study come from individuals who generously donate part of their brain in what is often an otherwise difficult situation," says Lein.

"In this case, her donation has an even higher level of importance and poignancy because these cells are so, so rare."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.