The human family tree is a tangle of twisted branches. Parting the foliage to disentangle the stem of our own species is not so easy.

The classic out-of-Africa hypothesis suggests that Homo sapiens evolved from a distinct lineage of early human that arose around 150,000 years ago before setting off to spread through Europe and beyond.

But there is another story. A genomic study led by researchers at McGill University and the University of California-Davis suggests our family history isn't a single straight line tracing back through a slowly changing population, but a web connecting a diversity of families stretching across the African continent.

The findings support a multiregional hypothesis, which argues that before our species left Africa for Europe, there was continuous gene flow between at least two different populations.

"At different times, people who embraced the classic model of a single origin for Homo sapiens suggested that humans first emerged in either East or Southern Africa," explains population geneticist Brenna Henn from the University of California Davis.

"But it has been difficult to reconcile these theories with the limited fossil and archaeological records of human occupation from sites as far afield as Morocco, Ethiopia, and South Africa which show that Homo sapiens were to be found living across the continent as far back as at least 300,000 years ago."

The oldest fossils in Africa that resemble our own species were found in Morocco, Ethiopia, and southern Africa. But it's not clear which of these regions hosts the true cradle of humankind.

Some researchers argue that's because we've been thinking about our human origins all wrong. Maybe the stem of our species is actually a braid of branches, created when a patchwork of co-existing populations migrate and mix.

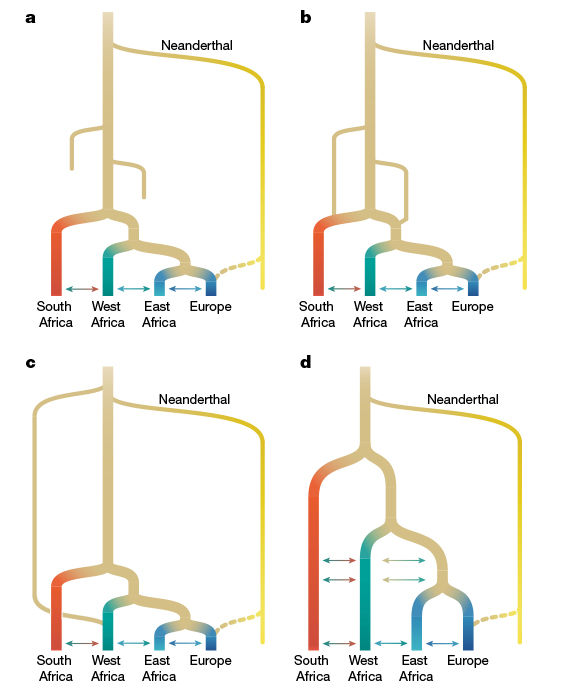

Genetic data seem to support that idea. Comparing the genomes of 290 modern-day people in South Africa, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, and Eurasia, researchers found evidence of high gene flow between their ancestors in eastern and western Africa.

They included genetic data from British individuals, to represent gene-flow back into Africa through colonial invasion, and a well-studied ancient Neanderthal genome from Croatia to account for genes from Neanderthals mixing with humans outside Africa.

Under a model of continuous migration, there could be two main lineages responsible for the genomes of those living in Africa today. These lineages represent distinct populations of early humans living in different parts of Africa around 400,000 years ago.

Models suggest after evolving independently for a stretch of time on opposing sides of the continent, the two populations might have merged, ultimately fracturing into subpopulations that persisted from 120,000 years ago.

"Shifts in wet and dry conditions across the African continent between 140 ka and 100 ka may have promoted these merger events between divergent stems," researchers write.

This intertwined lineage, they say, could have been the one to leave Africa for Europe around 50,000 years ago.

Although, that's not exactly what the genomic data suggested. Compared to the genomes of those with European ancestry, models predict that the first humans in Africa left for Europe 10,000 years after they should have.

Recent studies, however, suggest there may have been multiple waves of migration from Africa to Europe.

Given the sparse fossil record for this time, genomic sequencing has become an incredible tool for scientists retracing the steps of our ancestors.

The more genetic data experts read, the more complicated their story and ours becomes.

The study was published in Nature.