Normally, after running a five-year experiment, scientists might pat each other on the back in earnest recognition of having finally made it to the end of an epic, demanding research effort.

But if, after five long years, you're still less than 1 percent of the way through your actual experiment, the back-patting and champagne will have to wait. For another 495 years, in fact.

Amazingly enough, that's basically where we're at with a history-making microbiology experiment in Scotland. Having set out on a 500-year-long project that was started in 2014 (and set to finish in the year 2514), a team recently published the first results, based on data from the first two years of the research.

Why, you ask? At its heart, this bizarrely prolonged scientific endeavour has a uniquely simple premise: finding out how long microbes last in isolation.

"What exactly is the rate of loss of viability of microbes when they are dormant?" the researchers – based variously across Germany, Scotland, and the US – wondered, back when they first proposed the idea in 2014.

"What mathematical function describes their rate of death over long periods? Do some die quickly, leaving a core resistant population able to survive much longer periods?"

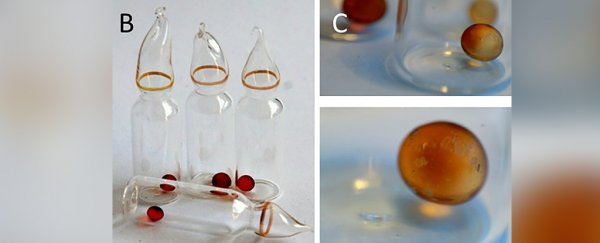

To answer these kinds of questions, the team sealed Bacillus subtilis spores, known for their ability to tolerate environmental extremes by maintaining a dormant state, in hundreds of glass vials.

Next, they began to play the waiting game – and then some – given the spores' heroic longevity "potentially far exceeds the human lifespan".

In addition to supplying the bacteria and the vials, you wouldn't want to be short on patience in the lab.

"It will be the longest planned scientific experiment yet created," the team proclaimed in 2014.

"Designed to investigate the survival of microbes and biomolecules over century time scales, it will go far beyond our existing incomplete knowledge."

In the experiment, every two years (for the first 24 years), a set of vials will be broken open to see how the spores are faring. Once the first 24 years are up, these periodic check-ins will slow down, occurring only once every 25 years, all the way until 2514.

Then we'll see who's bluffing whom – provided the world lasts that long, of course.

So far, based on the first reported results, the bacteria look like they're perfectly happy to wait this one out.

"Following two years of storage in the conditions for the 500-year experiment, there was no significant loss in spore viability," the authors explain, while pointing out it's far too early to know the long-term trajectory in these feats of endurance.

"While there are no significant differences in survivability, minor differences may lead to big differences as the 500-year storage study progresses… as storage time increases, spore resistance to these conditions may be dramatically affected."

The bacteria aren't the only ones under the microscope.

Given the insane duration of the experiment, the researchers who will carry the torch in future years will be expected to comply with rigorous methods –especially with the challenge of ensuring the experiment itself survives (not just the spores).

"At each 25-year time point, the researchers must copy the instructions to ensure longevity and keep instructions updated with regard to technological and linguistic development," the researchers explain.

"Because preservation is of the utmost importance, paper and ink of archival quality must be utilised."

Smart move.

The findings are reported in PLOS ONE.