A pair of fossils discovered in China reveal that ancestors to modern mammals were already taking to the air at least 160 million years ago.

The find suggests the group of animals that would eventually evolve into everything from bats to belugas were adapting to fill diverse niches quite early in their history, setting the groundwork for a global takeover with the demise of the dinosaurs.

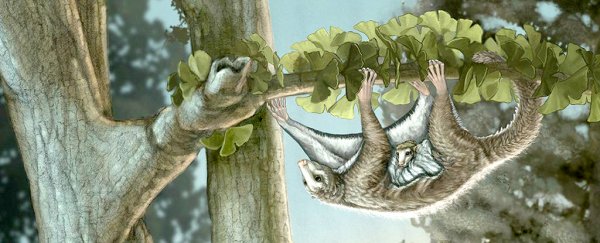

Maiopatagium furculiferum and Vilevolodon diplomylos aren't in any way closely related to "Rocky" the northern flying squirrel, but you could be forgiven for mixing them up.

Maiopatagium (which translates into "mother of wings") was 23 centimetres (about 9 inches) from nose to tail, and probably weighed around 120 to 170 grams (4 to 6 ounces). That makes it about the same size as Rocky, minus the hat and goggles.

The somewhat smaller Vilevolodon (or "gliding mammal") left a fossil just 8 centimetres (3 inches) long, and might have weighed a tiny 35 to 55 grams (1 to 2 ounces).

Both of these animals are what you'd call mammaliaformes – an ancient group of furry critters that gave rise to modern mammals.

To be more precise, the two species are examples of haramiyidans, a branch of herbivorous mammaliaformes that went extinct around 40 million years ago.

An international team of palaeontologists took a closer look at the fossilised specimens from Beijing Museum of Natural History to gain some insight into their tree-leaping habits.

Both of the fossils were highly detailed, clearly displaying membranes connecting their front and back limbs. Skeletal features in their shoulder joints and forelimbs suggested they were agile enough to use them for gliding, while their digits were well adapted to gripping onto branches much as bats do today.

The fused collar bones – or wishbones, if you're into chickens – of Maiopatagium was another convincing piece of evidence pointing at its aerial locomotion.

Reflecting its more primitive anatomy, Maiopatagium also had bones that connected its forelimbs that resemble those of a platypus, a mammal that also lays eggs called a monotreme.

Adding it all up, these two ancient platypus-like hipsters were leaping from tree to tree long before it was cool.

Both lived in the Jurassic period of the Mesozoic Era, a time when dinosaurs such as diplodocus and stegosaurus roamed the land.

What didn't roam the land was bats – it'd be another 100 million years before anything would hear the flutter of their tiny wings. As for real flying squirrels, the first of their kind wouldn't be tentatively throwing themselves off any branches for at least another 130 million years.

That makes these gliders the first known mammalian volants – a fancy word that describes animals that can move through the air.

"It's amazing that the aerial adaptions occurred so early in the history of mammals," says researcher David Grossnickle from the University of Chicago.

"Not only did these fossils show exquisite fossilisation of gliding membranes, their limb, hand and foot proportion also suggests a new gliding locomotion and behavior."

With these features in mind, we can speculate about the niche the two species filled in their environment.

There were no fruits or flowers in their world, with plant life being dominated by cycads, gingkoes, and conifers. The animals' teeth would have been perfectly suited to crushing up seeds and soft plant material such as new leaves.

More than just a nice example of how the same solutions to life's challenges pop up again and again through evolution, the discovery shows ancient mammals weren't all shrew-like furballs lurking in the shadows.

"With every new mammal fossil from the Age of Dinosaurs, we continue to be surprised by how diverse mammalian forerunners were in both feeding and locomotor adaptations," says researcher Zhe-Xi Luo from the University of Chicago.

These early example of winged mammals reveal that even while dinosaurs dominated the Jurassic, our own ancestors were already evolving a rich diversity of anatomical structures to take advantage of a range of ecological niches.

With the global changes that would see a radical drop in dino-diversity at the end of the Mesozoic, mammals had the goods to spread out and take over.

"The groundwork for mammals' successful diversification today appears to have been laid long ago," Luo said.

It might not have been the true flight of bats and birds, but it's amazing to know that at the dawn of mammals there were already some furry critters ready to take the leap.

This research was published in Nature.