Back in the 1800s, if a doctor wanted to look at a person's insides, they had to literally cut them open - a procedure that patients weren't exactly lining up for. But a man with a shotgun wound in the stomach presented an intriguing possibility - could you keep that hole open long enough to learn how digestion actually works?

Yep, a 19th-century doctor basically left a porthole on a man's side that he could unwrap, stick a piece of food inside, wait a bit, and then take it back out to see what happened. And even though that's a crazy thing to imagine, it's actually how we came to know that digestion is a chemical process.

The story starts back in 1822, with a doctor named William Beaumont, who worked as an army surgeon in northern Michigan - an area popular for fur trapping ay the time.

As Beaumont went about his daily job, he got an urgent call from a local fur store claiming that someone had just been shot with a shotgun and badly needed his attention.

When he got there, Beaumont found Canadian man, Alexis St. Martin - who had a notorious reputation for drinking too much and causing trouble - severely wounded from the blast. The gunshot struck his chest and abdomen, leaving a large hole in his midsection.

Beaumont - who, by the way, had no formal medical training, because back then, apprenticeship was the only real way to become a doctor - was able to save St. Martin after a lengthy operation to remove the metal from his wounds.

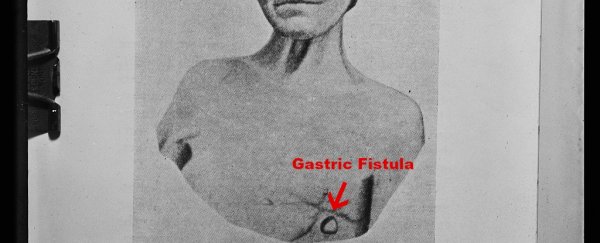

But despite several operations to help him recover, St. Martin had one lingering problem: a gaping fistula that had formed on his side as a result of the gunshot wound still hadn't been closed up.

A fistula is - for lack of a better word - a kind of 'tunnel' between two hollow areas of the body that's formed either intentionally by a surgeon or mistakenly by, say, a shotgun.

St. Martin's gunshot fistula had not been closed up, because he wouldn't sit through any more surgery - an extremely painful process in the days before anaesthesia. And it just so happened to give Beaumont direct access to St. Martin's stomach from the outside world.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

While this seems like an easy way to get an infection and die within a few days, especially given the era, St. Martin's stomach acid actually sanitised the wound, keeping it - for the most part - fairly healthy.

If you were to look inside a man's stomach fistula in a cold cabin in Michigan, what do you think would run through your mind? Would it be: 'I can finally figure out what's going on in there'?

If so, you and Beaumont would have a lot in common, because he stared into that fistula and saw nothing but opportunity.

Since St. Martin's fur trapping days were now over, Beaumont - partly out of self-interest and partly out of kindness - offered to hire St. Martin as a handyman to fix things around the property. In return, Beaumont would monitor St. Martin's wound and, you know, stick stuff in there to see what happened.

St. Martin agreed, and over the next couple decades - yes, decades - the two lived together. During this time, Beaumont took the opportunity and decided to figure out what the heck happens inside a stomach once and for all.

Back then, a few hypotheses were being kicked around about digestion, such as that it was done using muscle contractions to grind up food, or that it rotted inside people. But no one really knew.

For his experiments, Beaumont closely monitored all of the things St. Martin ate every day, and took samples of stomach acid out of the fistula, sending it off to be analysed by chemists.

Two years into this process, Beaumont made his first publication in the Philadelphia Medical Recorder - in a report entitled, A Case of Wounded Stomach.

As Beaumont explains in the report:

"This case affords an excellent opportunity for experimenting upon the gastric fluids and process of digestion. It would give no pain, nor cause the least uneasiness, to extract a gill of fluid every two or three days, for it frequently flows out spontaneously in considerable quantities.

Various kinds of digestible substances might be introduced into the stomach and then easily examined during the process of digestion. I may, therefore, be able hereafter to give some interesting experiments on these subjects."

When all was said and done, Beaumont published another paper, which recounted all of the experiments and came to the conclusion that hydrochloric acid and muscle movement were largely to blame for digestion. He also saw a link between digestion rate and disease, setting the stage for future experiments.

This initial discovery paved the way for other scientists to figure out all of the complexities of digestion and has even influenced other fields.

For example, Ivan Pavlov used a fistula when coming up with his famous dog experiment that brought about an understanding of classical conditioning, reports Tia Ghose at Live Science.

As for the duo, Beaumont lived until 1853, dying at the age of 67 after suffering a fall down some icy steps. St. Martin, who was lucky to be alive in the first place, went back to fur trapping, and eventually settled as a farmer, passing away in 1880 at age 83.

And there you have it. Thanks to the insane experiments of a single man and his - possibly too trustworthy - live-in patient, we formed the foundations that would lead us to an understanding of a vital part of our bodies.

Who's hungry?