If you thought you had a voracious appetite, you've got nothing on a newly discovered supermassive black hole.

The black hole at the center of a quasar galaxy called J0529-4351 is guzzling down so much material it basically swallows about a Sun's worth of gas and dust a day, onto a black hole that is already around 17 billion Suns' worth of mass.

That's the hungriest black hole we've spotted yet, says a team of astronomers led by Christian Wolf of the Australian National University, growing so fast that it's practically at the maximum limit of how much material it can accrete.

It represents a fascinating laboratory for understanding how supermassive black holes grow and evolve on the extreme end of the scale. But also, it's just really freaking awesome.

Supermassive black holes are a mind-boggling proposition. They're black holes millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun, and they can usually be found at the centers of galaxies, the giant gravitational blob around which the entire thing rotates.

The thing is, scientists don't really know how they got that way. Much smaller black holes – ones that are a few tens of solar masses – form from the direct collapse of the cores of massive stars when they die, and they can grow through collisions with other stellar-mass black holes.

But supermassive black holes are, frankly, too big for this formation channel to be efficient, particularly early in the Universe's history.

There are other theoretical formation channels, but one way we can better understand how supermassive black holes get so chonky is by looking for ones that are growing, and study them. This is where quasars – like J0529-4351 – enter the scene. These are galaxies with central black holes that are feeding ravenously.

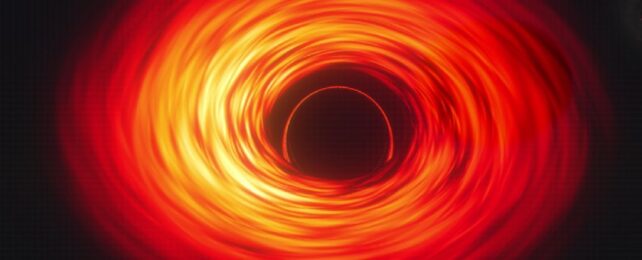

The black hole sits at the center of a huge, roiling, rotating mass of material that swirls around the black hole, feeding into it like water gurgling down a drain.

The intense friction and gravity causes this material to heat up to billions or even trillions of degrees, blazing brightly across space in light across the spectrum. Astronomers can study this light, teasing it apart to work out the properties of the black hole within.

J0529-4351 is a quasar found in the Cosmic Noon, around 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. That's very early in the history of the Universe – its light has traveled for more than 12 billion years to reach us – which makes its huge mass of 17 to 19 billion times the mass of the Sun (not the heftiest ever seen, but certainly getting up there) challenging to understand.

However, the rate at which the black hole is consuming matter could shed some light on its colossal size. Wolf and his team calculated that the black hole is growing at a rate of around 370 solar masses per year. That's a little more than the mass of the Sun falling onto the black hole every day.

Given the mass of the black hole, that's very close to a limit known as the Eddington limit. That's the maximum stable rate at which a black hole can feed. A black hole can briefly undergo super-Eddington accretion, but at these rates, the material starts to glow so strongly that the radiation pressure will push away the material around the black hole until it is out of gravitational reach.

That means that the black hole powering J0529-4351 is growing about as fast as it is able. Many quasars, in fact, appear to host black holes close to Eddington accretion; but J0529-4351 takes the biscuit. It's the brightest and most rapacious supermassive black hole we've seen to date.

"In terms of luminosity and likely growth rate," the researchers write, "J0529-4351 is the most extreme quasar known."

There's a lot we don't understand yet about J0529-4351. The mechanisms for its massive accretion are not yet known; a closer look using the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array in Chile could reveal how gas is moving around in the galaxy, and how the galaxy is spinning. The team also hopes to find other extreme quasars lurking in the distant reaches of space and time.

Although such extreme examples of these objects are rare, Wolf and his colleagues believe there lie more, waiting to be discovered, out there in the wide and wonderful cosmos.

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.