A huge seismic event that started in May of 2018 and was felt across the entire globe has officially given birth to a new underwater volcano.

Off the eastern coast of the island of Mayotte, a gigantic new feature rises 820 meters (2,690 feet) from the seafloor, a prominence that hadn't been there prior to an earthquake that rocked the island in May 2018.

"This is the largest active submarine eruption ever documented," the researchers wrote in their paper.

The new feature, thought to be part of a tectonic structure between the East African and Madagascar rifts, is helping scientists understand deep Earth processes about which we know relatively little.

The seismic rumbles of the ongoing event started on 10 May 2018. Just a few days later, on 15 May, a magnitude 5.8 quake struck, rocking the nearby island. Initially, scientists were perplexed; but it didn't take long to figure out that a volcanic event had occurred, the likes of which had never been seen before.

The signals pointed to a location around 50 kilometers from the Eastern coast of Mayotte, a French territory and part of the volcanic Comoros archipelago sandwiched between the Eastern coast of Africa and the Northern tip of Madagascar.

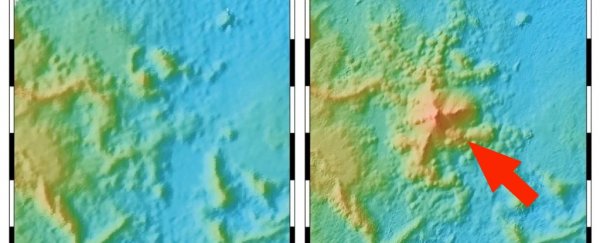

So a number of French governmental institutions sent a research team to check it out; there, sure enough, was an undersea mountain that hadn't been there before.

Led by geophysicist Nathalie Feuillet of the University of Paris in France, the scientists have now described their findings in a new paper.

The team began monitoring the region in February of 2019. They used a multibeam sonar to map an 8,600-square-kilometer area of seafloor. They also placed a network of seismometers on the seafloor, up to 3.5 kilometers deep, and combined this with seismic data from Mayotte.

Between 25 February and 6 May 2019, this network detected 17,000 seismic events, from a depth of around 20 to 50 kilometers below the ocean floor – a highly unusual finding, since most earthquakes are much shallower. An additional 84 events were also highly unusual, detected at very low frequencies.

Armed with this data, the researchers were able to reconstruct how the formation of the new volcano may have occurred. It started, according to their findings, with a magma reservoir deep in the asthenosphere, the molten mantle layer located directly below Earth's lithosphere.

Chronology of the eruption. (Feuillet et al., Nature Geoscience, 2021)

Chronology of the eruption. (Feuillet et al., Nature Geoscience, 2021)

Below the new volcano, tectonic processes may have caused damage to the lithosphere, resulting in dykes that drained magma from a reservoir up through the crust, producing swarms of earthquakes in the process. Eventually, this material made its way to the seafloor, where it erupted, producing 5 cubic kilometers of lava and building the new volcano.

The low-frequency events were likely generated by a shallower, fluid-filled cavity in the crust that could have been repeatedly excited by seismic strain on faults close to the cavity.

As of May 2019, the extruded volume of the new volcanic edifice is between 30 and 1,000 times larger than estimated for other deep-sea eruptions, making it the most significant undersea volcanic eruption ever recorded.

"The volumes and flux of emitted lava during the Mayotte magmatic event are comparable to those observed during eruptions at Earth's largest hotspots," the researchers wrote.

"Future scenarios could include a new caldera collapse, submarine eruptions on the upper slope or onshore eruptions. Large lava flows and cones on the upper slope and onshore Mayotte indicate that this has occurred in the past.

"Since the discovery of the new volcanic edifice, an observatory has been established to monitor activity in real time, and return cruises continue to follow the evolution of the eruption and edifices."

The research has been published in Nature Geoscience.