Step outside of the Milky Way for a moment and you might notice the bright disc of stars we call home has a weird warp to it. Now it seems the rest of our galaxy is also a little off-kilter.

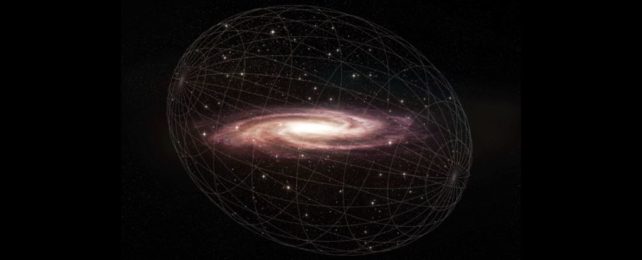

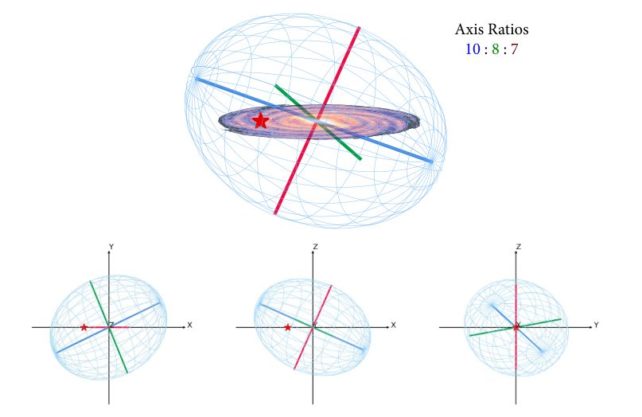

A new map of the stars above and below the galactic plane shows its galactic halo – the diffuse globe of gas, dark matter, and stars that surrounds spiral galaxies – is also wonky. Rather than the nice round sphere astronomers expected, the Milky Way's halo is a wibbly ellipsoid whose three axes are all different lengths.

"For decades, the general assumption has been that the stellar halo is more or less spherical and isotropic, or the same in every direction," says astronomer Charlie Conroy of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

"We now know that the textbook picture of our galaxy embedded within a spherical volume of stars has to be thrown out."

Determining the shape of our galaxy is really difficult to do. Imagine trying to figure out the shape of a vast lake while you're bobbing around in the middle of it. It's only in recent years, with the launch of the European Space Agency's Gaia telescope in 2013, that we've gained a detailed understanding of the three-dimensional shape of our galaxy.

Gaia shares Earth's orbit around the Sun. Changes in the telescope's position in the Solar System allows it to measure the parallax of objects in the Milky Way, obtaining the most accurate measurements to date for calculating the positions and movements of thousands of distant stars.

Thanks to this data, we now know that the Milky Way's disk is warped and bent. We also know that the Milky Way has repeatedly engaged in acts of galactic cannibalism, one of the most prominent of which seems to have been a collision with a galaxy we call the Gaia Sausage, or Gaia Enceladus, around 7 to 10 billion years ago.

This collision, scientists believe, created the Milky Way's stellar halo. The Gaia Sausage tore apart as it encountered our galaxy, its distinct population of stars scattering through the Milky Way's halo.

Led by astronomer and PhD student Jiwon "Jesse" Han of CfA, a team of scientists set out to gain a better understanding of the galactic halo and the Gaia Sausage's role in it.

"The stellar halo is a dynamic tracer of the galactic halo," says Han. "In order to learn more about galactic haloes in general, and especially our own galaxy's galactic halo and history, the stellar halo is a great place to start."

Unfortunately Gaia's data on the chemical abundances of halo stars beyond certain distances isn't overly reliable. Stellar populations can be tied together by their chemical abundances, making it important information for mapping the relationship between the halo's stars.

So the researchers added data from a survey called Hectochelle in the Halo at High Resolution, or H3; a ground-based survey that has collected, among other characteristics, chemical abundance data on thousands of stars in the Milky Way's stellar halo.

With this data, the researchers inferred the density profile of the stellar population of the Milky Way's halo. They found that the best fit for their data was a football-shaped halo, tilted 25 degrees with respect to the galactic plane.

This fits with previous studies that found the stars in the Milky Way's halo occupy a triaxial ellipsoid formation (although the specifics vary a little). It also fits with the theory that the Gaia Sausage created, or at least played a huge role in creating, the Milky Way's halo. The skewiff shape of the halo suggests that the two galaxies collided at an angle.

The researchers also found two pileups of stars at significant distances from the galactic center. These collections, they found, represent the apocenters of the initial stellar orbits around the galactic center – the farthest distance the stars travel in their elongated, elliptical orbits.

Just as an orbiting body speeds up on reaching the point closest to its center of attraction, or 'pericenter', the apocenter is a point of slow-down. When the Gaia Sausage met with the Milky Way, its stars were flung out into two wild orbits, slowing down at the apocenters – to the point of stopping, and just making that location their new home.

However, this was a very long time ago, long enough that the odd shape should have resolved itself long ago, settling back into a sphere. The strong tilt suggests that the halo of dark matter binding the Milky Way – a mysterious mass responsible for excess gravity in the Universe – is also highly tilted.

So, while it appears we have some new and exciting answers, we also have some new and exciting questions. Ongoing and future surveys, the researchers said, should provide even stronger constraints on the shape of the halo to help figure out how our galaxy evolved.

"These are such intuitively interesting questions to ask about our galaxy: 'What does the galaxy look like?' and 'What does the stellar halo look like?'," Han says.

"With this line of research and study in particular, we are finally answering those questions."

The research has been published in The Astronomical Journal.