Leonardo da Vinci is well known for having used less conventional painting methods and substances in his work, and we're still making new discoveries about them – the latest being a mix of toxic pigments underlying the brushwork on the Mona Lisa.

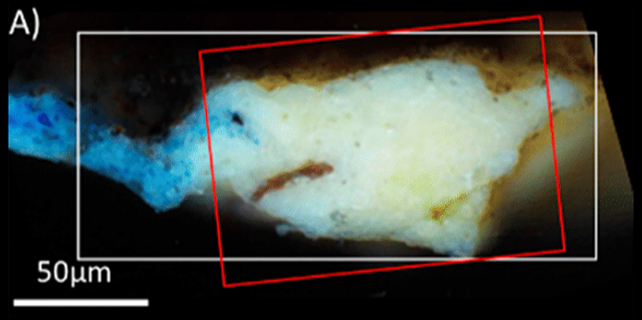

Researchers from France and the UK looked at a tiny microsample taken from a hidden corner of the Mona Lisa, deploying a variety of X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy imaging techniques to identify the substances used.

The team found not only oil and lead white – as expected – but also the rare compound plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)3O(OH)2). Plumbonacrite is formed when oil and lead(II) oxide (or PbO) react together, suggesting the latter compound was used by da Vinci.

"Leonardo probably endeavored to prepare a thick paint suitable for covering the wooden panel of the Mona Lisa by treating the oil with a high load of lead(II) oxide, PbO," write the researchers in their published paper.

The same PbO compound was found in several microsamples taken from the surface of The Last Supper, another famous painting from da Vinci. However, the only references to PbO in the Italian artist's writings were related to skin and hair remedies.

Even though it's not included in his writings, it nevertheless seems that da Vinci made use of this lead(II) oxide as a ground layer. It's something that's been hypothesized about before, but now we have more direct evidence of it.

It's thought that the lead(II) oxide power would've been heated and dissolved in linseed or nut oil by da Vinci, producing a mixture that's thicker and faster drying than traditional oil paints – a recipe that then went on to be used by other artists.

The same plumbonacrite substance has also been discovered in The Night Watch painting by Rembrandt, created in 1642 – almost a century and a half after the Mona Lisa. That suggests the Dutch master used a similar technique to da Vinci.

This discovery is another example of how modern-day analysis techniques are opening up new findings about historical artifacts. Advanced 3D rendering has previously been used to help study another da Vinci painting, Salvator Mundi.

It's also testament to the constant inventiveness of Leonardo da Vinci, a man who achieved greatness not just in his painting, but also in many other fields – including mathematics, chemistry, and engineering.

"He was someone who loved to experiment, and each of his paintings is completely different technically," chemist Victor Gonzalez, from the Institut de Recherche de Chimie Paris in France, told the Associated Press.

The research has been published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.