The formation of the Moon may have come harder on the heels of Earth's birth than we thought.

According to a new analysis by researchers from the US, France, and Germany, Earth's constant companion may have formed as early as 4.53 billion years ago – hundreds of millions of years earlier than previous estimates.

It's a timeline that maybe even solves other mysteries about the Moon, such as why there are fewer huge impact basins than we expect, and why it has less metal compared to Earth. It could even help us better understand the history and evolution of our own planet, says a team led by geologist Francis Nimmo of the University of California Santa Cruz.

The current leading theory for how the Moon formed is predicated on the chaos of the early Solar System. The Sun formed around 4.6 billion years ago; at that time, it was surrounded by a disk of gas and dust left over from its own formation, coalescing into rocks that clumped together, smacked into each other, and generally contributed to an air of mayhem.

Scientists think the Moon formed when a large object, around the size of Mars, collided with a baby Earth, which was still warm and gooey from its own formation. A huge amount of Earth's mass could have been ejected into orbit, where it came together to form the Moon.

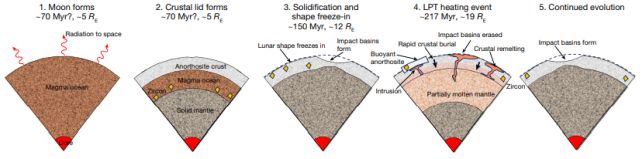

After its formation, the Moon is thought to have hosted a global magma ocean that rapidly cooled and solidified into the lunar surface. Based on samples of Moon rock that were assumed to have formed in this magma ocean, the collision is estimated to have occurred 4.35 billion years.

But more recently, a different picture has emerged from tiny grains of lunar zircon.

Zircon crystals are an excellent way to find the age of a sample because of a quirk of the way they form. When they are forming, zircon crystals incorporate uranium, but strongly reject lead. Over time, the radioactive uranium in the zircon decays into lead at a very well understood rate.

Scientists can look at the ratios of uranium to lead in a zircon crystal and work out how long ago the zircon formed, with a high level of accuracy.

What's interesting is that zircon crystals from the Moon have been dated at ages that are significantly higher than 4.35 billion years. One came in at 4.46 billion years; another at 4.51 billion years. These are incompatible with a global magma ocean, which would preclude the formation and survival of zircon crystals.

Somehow, these zircons exist. At the same time, there are a large number of lunar rocks that are 4.35 billion years old. To resolve this apparent discrepancy, Nimmo and his colleagues performed analyses and modeling to show that both can be true – if the Moon formed at an earlier time, and then underwent widespread crustal remelting 4.35 billion years ago.

When two bodies orbit each other, the path of the orbit usually isn't a nice neat circle, but instead traces an ellipse, a property known as eccentricity. The changing proximity of the two bodies to each other also produces a change in the gravitational pull felt by each object as they move closer to and farther from the other. This constantly changing tug exerts a tidal force on each object, stretching and squishing it and warming it up through constant friction.

Back when the Moon was newly formed, before it settled into a more circular orbit, the Moon's orbit may have been eccentric enough to melt parts of its surface for a few tens of millions of years. This could have been around 4.35 billion years ago – neatly resolving the problem of the older zircon and the younger surface rock.

This, in turn, constrains the age of the Moon to between 4.43 and 4.53 billion years ago. Since Earth is estimated to be 4.54 billion years old, that means our planet may have been best buddies with its satellite for almost its entire lifespan.

The finding could help resolve some interesting mysteries. The Moon has fewer impact basins than scientists expect based on how heavy they estimate that early bombardment to have been. A tidal remelting of the lunar surface would have effectively erased any such impact basins. This also places constraints on the age of the huge South Pole-Aitken Basin that covers a quarter of the Moon's surface.

In addition, Earth has metals on its surface from planetesimals that smacked into it during the early Solar System bombardment. The Moon has considerably less. If the Moon formed, collected some planetsimals, and remelted, those metals would have sunk out of view below the lunar surface.

Unless aliens came along and threw zircons all over the Moon just for a giggle. In that case, all bets are off.

The research has been published in Nature.