Hurricanes are the costliest natural disasters in the United States.

Hurricane Harvey, which ravaged parts of Texas in August 2017, cost the US US$125 billion (yes, billion with a 'b'). Harvey's total came second only to that of Hurricane Katrina, which hit Louisiana in 2005 and cost approximately US$161 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Economic losses from Katrina exceeded 1 percent of the US's gross domestic product that year.

According to a study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, extremely destructive storms like Harvey and Katrina – hurricanes that decimate large coastal areas to the tune of billions of dollars – have gotten far more common in the US relative to their less damaging counterparts.

"We estimate that there has been a tripling in the rate of the most damaging storms over the last century," Aslak Grinsted, the lead author of the study, told Business Insider.

Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. (Barbara Ambrose/NOAA)

Aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. (Barbara Ambrose/NOAA)

Hurricanes in the US are becoming more damaging

A large body of research has shown links between higher temperatures and stronger, wetter hurricanes that can cause more damage. But calculating the cost of those worsening storms is tricky.

Analyses have to factor in inflation and fluctuations in property costs, as well as the fact that more people live in vulnerable coastal areas than they did a century ago. So if the same storm were to hit an urban area today versus 100 years ago, the resulting damages are likely to be higher.

In their new study, Grinsted and his team found a new way to compare hurricane impacts across centuries. They elected to compare storms by the amount of impacted land area, rather than economic losses.

Using an insurance-industry database, the researchers calculated how much land was destroyed by more than 240 tropical storms and hurricanes that made landfall in the US between 1900 and 2018.

"We cannot directly compare the damage from the 1926 Great Miami hurricane with that from Hurricane Irma in 2017 without considering the increased amount of valuable property exposed," the authors wrote.

So Grinsted coined a new metric: "area of total destruction," or ATD. It's a measurement of how big an area a given hurricane would have to destroy to equal the associated economic losses.

The study authors concluded that the frequency of the most damaging hurricanes (defined as ATDs exceeding 467 square miles; 1,200 square kilometres) increased 330 percent century-over-century.

Moderate storms with an ATD of 50 square miles (130 square kilometres) or less, by comparison, increased at a rate of 140 percent per century.

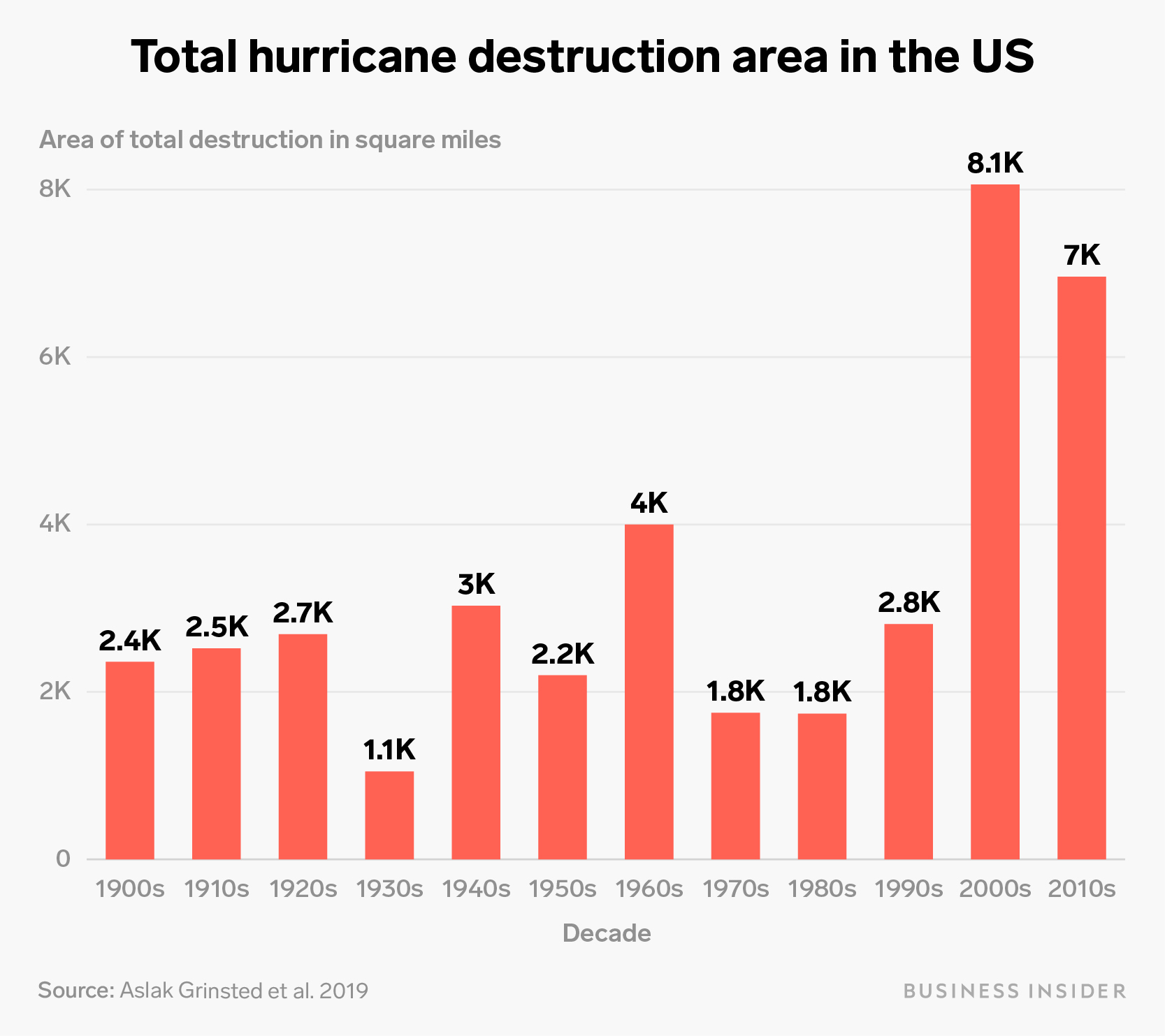

(Shayanne Gal/Business Insider)

(Shayanne Gal/Business Insider)

The data revealed that the worst hurricanes were Katrina and Harvey, which both exceeded an ATD of 1,930 square miles (4,990 square kilometres).

According to Grinsted, the 2000s was the decade with the greatest aggregate ATD thus far.

That trend holds true regardless of whether the data set includes tropical storms and hurricanes, or just hurricanes. (A tropical storm becomes a hurricane after wind speeds top 74 mph; 119 km/h.)

Why hurricanes are getting stronger

Scientists can't definitely say whether individual storms are directly caused by climate change, but warming overall makes hurricanes more frequent and devastating than they would otherwise be.

That's because oceans absorb 93 percent of the extra heat that greenhouse gases trap in the atmosphere, and hurricanes use warm water as fuel. So a 1-degree Fahrenheit rise in ocean temperature can increase a storm's wind speed by 15 to 20 miles per hour (24 to 32 km/h), according to Yale Climate Connections.

Plus, rising water temperatures lead to sea-level rise, which increases the risk of flooding during high tides and in the event of storms surges. Warmer air also holds more atmospheric water vapour, which enables tropical storms to strengthen and unleash more precipitation.

Interstate 69 inundated by Tropical Storm Harvey floodwaters in 2017. (AP/David J. Phillip)

Interstate 69 inundated by Tropical Storm Harvey floodwaters in 2017. (AP/David J. Phillip)

Hurricanes also appear to be getting more sluggish – a slower pace of movement gives a storm more time to lash an area with powerful winds and dump rain, so its effects can wind up feeling more intense.

Over the past 70 years or so, the speed of hurricanes and tropical storms has slowed about 10 percent on average, according to a 2018 study.

"Nothing good comes out of a slowing storm," James Kossin, a NOAA scientist, told National Geographic. "It can increase the amount of time that structures are subjected to strong wind. And it increases rainfall."

Hurricane Harvey was a prime example of this. After it made landfall, Harvey stalled for days and dumped more than 51 inches (130 centimetres) of rain on the Houston area. Climate scientist Tom Di Liberto described it at the time as the "storm that refused to leave."

To make matters worse, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, so a 10 percent slowdown in a storm's pace could double the amount of rainfall and flooding that an area experiences. The peak rain rates of storms have increased by 30 percent over the past 60 years.

Both predictive climate models and Grinsted's new data suggest that more destructive hurricanes will continue to increase in frequency unless greenhouse gas emissions are curbed. But until that happens, Grinsted said, we have to prepare for what scientists know is coming.

"In the short term, we cannot hope to combat storms. So the risk has to be reduced in other ways: adapting, and reducing exposure," he said. "It is also important to keep improving forecasting."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: