It was only January of this year when astronomers excitedly announced the discovery of the most Earth-like exoplanet ever found: Kepler–438b, a near-Earth-sized world some 470 light-years away in the Lyra constellation.

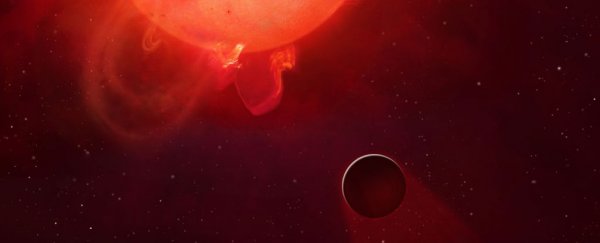

Lying within the habitable zone of its red dwarf star, meaning water could theoretically exist on the surface of the planet, it was deemed one of the likeliest hosts for life outside our Solar System. However, according to a new study, Kepler–438b's proximity to its sun also makes it susceptible to another, less accommodating phenomenon: massive solar flaring called 'superflaring', which may well have rendered the planet uninhabitable.

According to researchers from the Astrophysics Group at the University of Warwick in the UK, Kepler–438b – which to date is the exoplanet with the highest recorded Earth Similarity Index – is subject to superflares that are approximately 10 times more powerful than the flares from our own Sun. In terms of energy, these superflares are the equivalent of almost 100 billion megatonnes of TNT.

"Unlike Earth's relatively quiet Sun, Kepler–438 emits strong flares every few hundred days, each one stronger than the most powerful recorded flare on the Sun," said David Armstrong, lead researcher on the paper.

In the worst-case scenario, it's possible that the flaring could result in what's called a coronal mass ejection, in which a huge amount of plasma hurls outwards from the sun and could even strip a planet's atmosphere away. According to the researchers, such a scenario has probably eventuated on Kepler–438b.

"It is likely that these flares are associated with coronal mass ejections, which could have serious damaging effects on the habitability of the planet," said Armstrong. "If [Kepler–438b] has a magnetic field like Earth, it may be shielded from some of the effects. However, if it does not, or the flares are strong enough, it could have lost its atmosphere, be irradiated by extra dangerous radiation and be a much harsher place for life to exist."

While it's still possible that organisms could survive in irradiated circumstances if Kepler–438b has retained its atmosphere up until now, the chances of finding life there are starting to look progressively slimmer – and pretty much shrink to zero if a coronal mass ejection has indeed taken place.

"The presence of an atmosphere is essential for the development of life," said Chloe Pugh, co-author of the research published online at arXiv.org . "With little atmosphere, the planet would also be subject to harsh UV and X-ray radiation from the superflares, along with charged particle radiation, all of which are damaging to life."

It's pretty sad news given there aren't actually that many exoplanets that scientists have discovered which look like they could sustain life. Hopes will now switch to some of these other candidates, including the recently discovered and much-hyped Kepler–452b (aka Earth 2.0).