A set of mysterious 'hoofprints' on the seafloor off the coast of New Zealand are not actually the work of a mythic underwater horse trotting through the abyss.

As it turns out, there's a more scientific explanation than that – one that helps reveal some of the more elusive characters living in the ocean's depths.

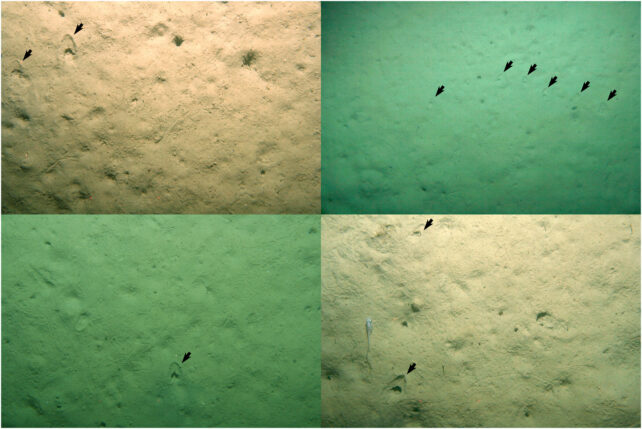

The strange markings were first discovered back in 2013 during a survey of an undersea submarine ridge, conducted by New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

In all the years since then, no one could figure out what had made the smattering of imprints more than 450 meters deep.

Now, researchers at NIWA have found a solution that fits snuggly within the cryptic impressions.

They say the triangular-shaped markings line up perfectly with the pointed snouts of some species of deep-sea rattail fish, otherwise known as grenadiers (Coelorinchus).

The divots in the middle of the sandy imprints are probably central 'bitemarks', where the bottom-feeders chomped down on the mud and sucked up prey.

Given the extreme depths at which these rattail fish forage, bite marks of this kind are "rarely, if ever, encountered," write researchers from NIWA.

In fact, the team is not aware of any documented observations of a rattail's natural foraging behavior in action.

The bite marks found near New Zealand are some of our only evidence of their true feeding habits.

Judging by their nose prints, researchers at NIWA suspect the fish hunt by shoving their snouts into the mud, probably with "a short burst of speed", before sucking up their prey with their downward-facing mouths.

Some of the impressions are shallower than others and were probably made from the fish grabbing a crab or a snack on the surface of the sand.

The deeper bites, on the other hand, could indicate an attempt to dig up a meal somewhat buried in the sediment.

"NIWA uses a technology called the Deep Towed Imaging System (DTIS) to allow us to see the seafloor in stunning detail. When our people review this footage, they often see markings in the sediment, but unfortunately, most of them are unknown to science and we can only guess what might have made them, let alone find convincing proof," says marine biologist Sadie Mills from NIWA.

"It is so cool to finally have the validation that what we saw on the video was actually rattails feeding in the mud. It's like getting a nice reward at the end of many years of watching DTIS footage."

Finding food in the deep dark ocean is tricky work, which is why rattails have evolved keen eyesight, acute sniffing power, and sensitive barbels on their chinny chin chins.

Cruising just above the seafloor, the fish use these senses to seek out crustaceans, worms, and other fishes to eat.

Yet how they pull off these attacks is a bit mysterious.

Way back in the 1970s, scientists caught sight of a deep-sea grenadier 'rooting about' in the muddy seafloor, roughly 4,000 meters deep.

What it was looking for in the sediment was unclear, but at the time, scientists speculated that the behavior should leave a mark on the seafloor.

Now, that hypothesis has finally been realized.

When researchers overlayed some photos of rattail fish on the undersea 'hoofprints', the heads of three species matched up with the impressions.

While many of the marks were too ill defined to connect to a specific species of rattail fish, there were two impressions that fit very closely with the heads of two different fish: one, called the rough-head whiptail or the oblique banded rattail (Coelorinchus aspercephalus), and the other called the two-barred whiptail (C. biclinozonalis).

Very little is known about either.

"The reason we could point to a specific species is because of their unique head features – these types of rattails have a long snout and an extendable mouth on the underside of their head that allow them to feed off the seafloor, something that other species do not," explains Stevens.

"I had a hunch this might work but I was really surprised how well the head profile images matched the impressions."

Emboldened by their discovery, researchers at NIWA now hope to use these markings to identify critical habitats and feeding zones for these slippery fish.

The study was published in Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers.