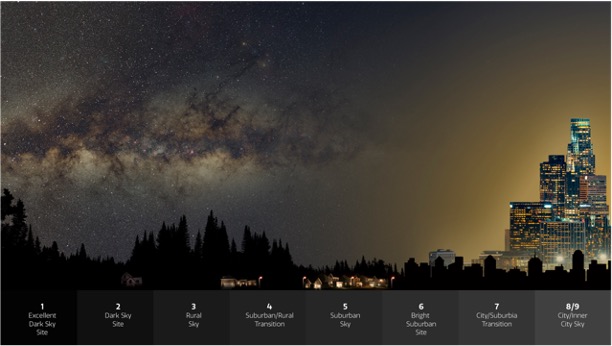

As city folk sleep blanketed by the warm glow of artificial light that surrounds urban centers, stargazers feel the chill of the night sky and see all its constellations being smudged into a fuzzy blur by those same urban lights.

It's a worrying trend that stretches back decades. In 1973, astronomer Kurt Riegel warned that artificial lighting was rapidly changing our view of the night sky. Since then, we've learned that light pollution from expanding urban areas also harms ecosystems and insect populations.

A new study shows that the night sky is getting brighter at a staggering rate worldwide and much faster than satellites had previously indicated. In other words, the dimmest stars in the night sky are fast disappearing as artificial light illuminates the night sky.

Based on observations from over 50,000 citizen scientists worldwide who compared their view of the stars to maps of starry skies showing different levels of light pollution, GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences physicist Christopher Kyba and colleagues found that the night sky has brightened by roughly 7 to 10 percent every year, from 2011 to 2022.

That's equivalent to the night sky doubling in brightness in fewer than eight years or more than quadrupling in 18 years. The researchers estimate that a child born under a night sky with 250 visible stars would see fewer than 100 stars in that same patch of darkness by the time they finish school.

They suspect this recent trend towards brighter night skies is partly because of the installation of modern LEDs (light-emitting diodes), which emit more light for a given power than incandescent light bulbs.

Satellites that measure global skyglow are often 'blind' to the blue light that LEDs produce, unable to detect wavelengths below 500 nm. These shorter wavelengths of light also scatter more easily in the atmosphere than longer wavelengths do, creating a vast haze that stops the night sky from ever fully darkening.

"The visibility of stars is deteriorating rapidly, despite (or perhaps because of) the introduction of LEDs in outdoor lighting applications," write the researchers in their published paper.

"Existing lighting policies are not preventing increases in skyglow, at least on continental and global scales."

Citizen scientists in North America reported the greatest increases in sky brightness, at an average of 10.4 percent per year; the night skies over Europe brightened at a slower rate, around 6.5 percent a year.

Though it is a crude average, the rest of the world is seeing light pollution brighten their starry skies by 7.7 percent each year.

This dwarfs the estimates from satellite measurements of global skyglow, which had detected night sky brightness increasing by 2.2 percent each year between 2012 and 2016, up from a yearly brightening rate of 1.6 percent in the 25 years prior.

While the analysis depends on observations logged by citizen scientists who were mainly from North America and Europe, because they looked at stars visible to the naked eye, the analysis accounts for changes in both the radiance and spectral profile of the night sky – whether light is bluer or redder, made up of shorter wavelengths or longer ones.

Adding to what we know about the heavy glow of artificial light, the study reveals just how fast humans have altered our view of starry skies.

"Looking at the International Space Station's images and videos of Earth's night hemisphere, people generally are only struck by the 'beauty' of the city lights, as if they were lights on a Christmas tree. They do not perceive that these are images of pollution," Fabio Falchi and Salvador Bará, two physicists and dark sky advocates at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, write in a perspective on the new study.

"It is like admiring the beauty of the rainbow colors that gasoline produces in water and not recognizing that it is chemical pollution."

To make matters worse, thousands of satellites launched into low Earth orbit in the past few years are also obscuring astronomers' ability to study the cosmos.

Scientists have moved their observatories away from city limits, but these shiny satellites reflect the Sun's rays into the sightlines of optical telescopes and transmit radio waves at the same frequencies that radio telescopes use.

While those satellites are beyond the reach of citizen scientists, Kyba and colleagues are enlisting their help once again to create an inventory of outdoor lighting to better understand the sources of light pollution.

Falchi and Bará also suggest a few strategies to control light pollution, much like air quality guidelines have curbed air pollution. Total caps and 'red line' limits on the production of outdoor lights could complement other efforts to preserve dark skies in designated places where artificial light has not yet tainted the inky blackness.

The study and the perspective are published in Science.