Scientists working with mice have zeroed in on the cells responsible for the most common and aggressive form of ovarian cancer.

If the discovery in the oviducts (uterine tubes) of mice extends to the fallopian tubes of humans, it could provide early detection of deadly high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas (HGSOC), which claim the lives of most patients within just five years of detection.

More than a decade ago, evidence started accumulating to suggest many ovarian cancers in humans do not start in the ovaries but in the fallopian tubes.

In the years since, scientists have found lesions at the ends of fallopian tubes that are genetically tied to tumors in the ovaries. Still, the exact cells within the fallopian tubes that are responsible for HGSOC are unknown.

Often, there are no symptoms at all to tip off patients or doctors, and today, about 80 percent of HGSOC cases are detected at an advanced stage when treatment options are limited.

"Detection and treatment of HGSOC at earlier stages could be crucial to improving the prognosis of patients with this malignancy," explain researchers led by Cornell University pathologist Alexander Nikitin.

"However, identification of new diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets is hindered by our inadequate knowledge about the cells in which HGSOC originates and the mechanisms underlying disease initiation."

A 2013 study by Nikitin and colleagues identified stem cells in the ovaries that can lead to HGSOC, but their newest study on mice is the first to find cancer-prone cells in the oviduct.

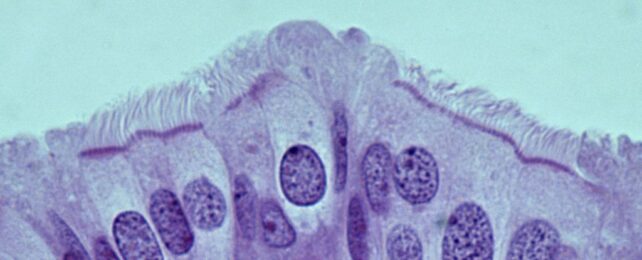

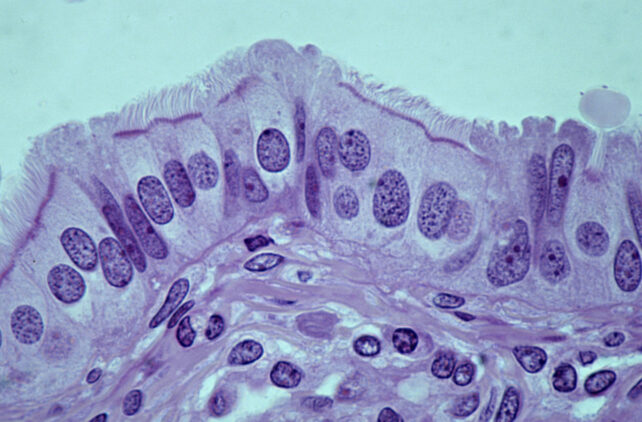

In fact, Nikitin and his team have characterized and listed all the cell types found in the oviduct for the first time.

"The question was, to what extent all of the cells contribute to ovarian cancer," explains Nikitin.

Unlike in the ovaries, the most cancer-prone tissues in the mouse oviducts weren't stem cells.

Instead, the units most prone to cancer were pre-ciliated cells. These are transitional cells that are on their way to becoming ciliated cells from stem cells. Once they form short, hair-like membranes, they help push oocytes along the mouse's oviduct, or through fallopian tubes in humans.

Two genetic mutations associated with HGSOC, however, seem to cause these pre-ciliated cells some trouble.

The team found that when the mutations are present in mice, the pre-ciliated cells in the oviduct lead to efficient cancer formation.

The results suggest there is a link between the regulation of cilia formation in the uterine tubes and ovarian cancer.

Interestingly, issues with ciliogenesis are also linked to pancreatic cancer.

If the cells that cause many cases can be identified in humans, the discovery could save numerous lives in the future.

Further studies are now needed to explore the mechanisms behind ovarian tumor formation, and to explore whether other genetic mutations associated with HGSOC have similar or different effects.

"We not only identified cells where the cancer originates," says Nikitin, "but we identified mechanisms which can be potentially used for new therapeutics and new diagnostic tools."

The study was published in Nature.