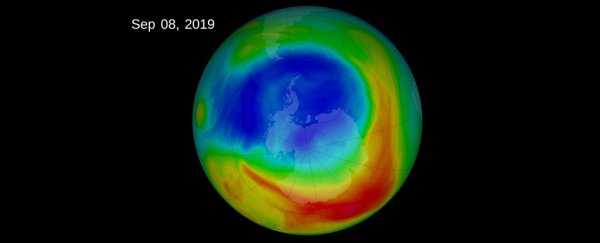

The ozone layer above Antarctica has recovered so much, it's actually stopped many worrying changes in the Southern Hemisphere's atmosphere. If you're looking for someone to thank, try the world at large.

A new study suggests the Montreal Protocol - the 1987 agreement to stop producing ozone depleting substances (ODSs) - could be responsible for pausing, or even reversing, some troubling changes in air currents around the Southern Hemisphere.

Swirling towards our planet's poles at a high altitude are fast air currents known as jet streams. Before the turn of the century, ozone depletion had been driving the southern jet stream further south than usual. This ended up changing rainfall patterns, and potentially ocean currents as well.

Then, a decade or so after the protocol was signed, that migration suddenly stopped. Was it a coincidence?

Using a range of models and computer simulations, researchers have now shown this pause in movement was not driven by natural shifts in winds alone. Instead, only changes in the ozone could explain why the creep of the jet stream had suddenly stopped.

In other words, the impact of the Montreal Protocol appears to have paused, or even slightly reversed, the southern migration of the jet stream. And for once, that's actually good news.

In Australia, for instance, changes to the jet stream have increased the risk of drought by pushing rain away from coastal areas. If the trend does reverse, those rains might return.

"The 'weather bands' that bring our cold fronts have been narrowing towards the south pole, and that's why southern Australia has experienced decreasing rainfall over the last thirty years or so," says Ian Rae, organic chemist from the University of Melbourne who was not involved in the study.

"If the ozone layer is recovering, and the circulation is moving north, that's good news on two fronts (pun not intended)."

Still, we may not be celebrating for long. While improvements in cutting back our reliance on ODSs have certainly allowed the ozone to recover somewhat, carbon dioxide levels continue to creep upwards and place all that progress at risk.

Last year, the Antarctic ozone hole hit its smallest annual peak on record since 1982, but the problem isn't solved, and this record may have something to do with unusually mild temperatures in that layer of the atmosphere.

What's more, in recent years, there's been a surge in ozone-depleting chemicals, coming from industrial regions in China.

"We term this a 'pause' because the poleward circulation trends might resume, stay flat, or reverse," says atmospheric chemist Antara Banerjee from the University of Colorado Boulder.

"It's the tug of war between the opposing effects of ozone recovery and rising greenhouse gases that will determine future trends."

The Montreal Protocol is proof that if we take global and immediate action we can help pause or even reverse some of the damage we've started. Yet even now, the steady rise in greenhouse gas emissions is a reminder that one such action is simply not enough.

The study was published in Nature.