It's been a big year for the 'impossible' EM Drive - a new kind of rocket engine that appears to generate thrust without any kind of exhaust or propellant. Back in May, NASA researchers reported a successful 10-week trial of their EM Drive prototype, and inventor Guido Fetta just got approval to test his own version in space.

Now, the UK Intellectual Property Office has released the latest patent application from British EM Drive inventor Roger Shawyer, and he says millions of pounds rest on the success of design within.

"The patent process is a very significant process, it's not like an academic peer review where everyone hides behind an anonymous review, it's all out in the open," Shawyer told Mary-Ann Russon at the International Business Times.

"This is a proper, professional way of establishing prior ownership done by professionals in the patent office, and in order to publish my patent application, they had to first carry out a thorough examination of the physics in order to establish that the invention does not contravene the laws of physics."

For the uninitiated, the EM Drive was first invented by Shawyer back in 1999, and despite experimental evidence suggesting that such an engine could work, it's been courting controversy ever since.

Why? Well, it just so happens to violate one of the most fundamental laws of physics we have: Newton's Third Law, which states, "To each action there's an equal and opposite reaction."

In its most basic form, the EM Drive uses electromagnetic waves as 'fuel', creating thrust by bouncing microwave photons back and forth inside a cone-shaped closed metal cavity. This causes the 'pointy end' of the EM Drive to accelerate in the opposite direction that the photons are pushing.

But there's the problem - "an equal and opposite reaction" means something needs to be pushed out the back of propulsion system in order for it to move forwards, and the EM Drive doesn't have an exhaust.

Newton's Third Law states that without an exhaust, you can't produce thrust, but experiments from NASA and a number of other research teams from around the world have shown that not only can the EM Drive produce thrust - it can theoretically produce enough to power an entire spacecraft.

If we can power spacecraft with such an engine, it could replace the incredibly expensive and heavy rocket fuel that's been a major hurdle in getting us much of anywhere in the Solar System.

As Harold (Sonny) White, leader of the research group over at NASA's Eaglework Laboratories, says, a crewed mission to Mars in an EM Drive-powered spacecraft could arrive at Mars in a mind-boggling 70 days. That's less than half the time NASA has estimated it will take using current technology.

Since Shawyer proposed such a device almost two decades ago, he's been busy trying to beat everyone else to the punch, applying for patent after patent with every tweak he makes.

His latest patent has just been made public, and describes a new thruster design that features a single flat superconducting plate on one end, with a uniquely shaped, non-conducting plate on the other.

He says this is necessary to minimise the internal Doppler shift - a change in frequency or wavelength of a wave for an observer moving relative to its source - and also keep manufacturing costs down.

"This is pretty significant, because it enables you to easily manufacture these things, and we want to produce thousands of them," he told Russon at the International Business Times. "The patent makes the construction of a viable superconducting thruster easier, and it will produce a lot of thrust."

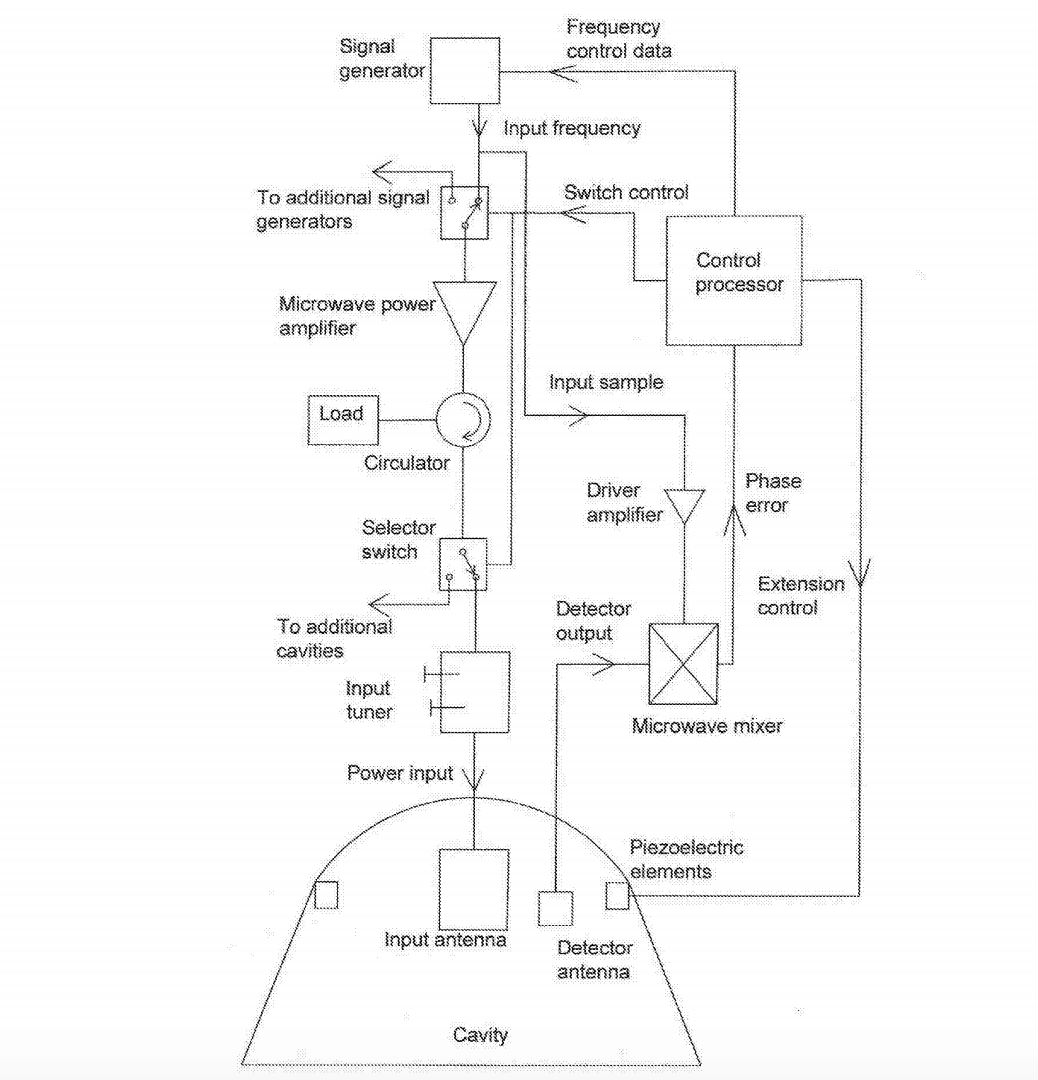

You can access the patent here, but here's a taste of the contents, with a rundown of just one component - the control circuit:

Shawyer et. al.

Shawyer et. al.

According to Russon, Shawyer is working with an unnamed UK aerospace company to develop his second generation EM Drive, which he says will produce thrust many orders of magnitude greater than that observed by NASA's Eagleworks team or any other laboratory.

We'll have to wait and see once he gets his invention out of the lab and into space, like this entrepreneur is planning to do in the coming months.

And in the meantime, we've got a milestone paper coming up, because the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) has finally confirmed that a paper by the Eagleworks team has been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication in December.

We can't wait to see what the critics will do with that.