We've yet to see a falling piece of space debris strike an airplane, but if it happens, the consequences would almost certainly be catastrophic – and according to a new study, the danger posed to planes is only rising.

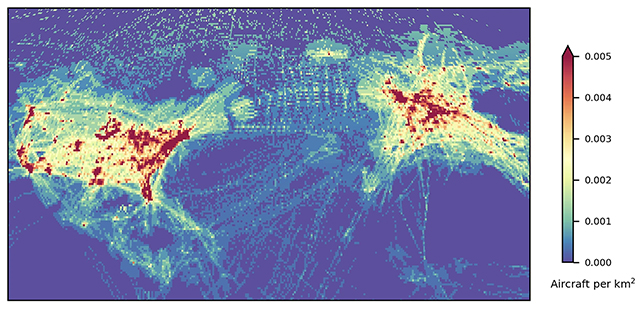

The researchers behind the study, from the University of British Columbia in Canada, looked at worldwide flight data to model the distribution of planes in the sky, then compared this to records of uncontrolled rocket body reentries.

The increasing risk is also being driven in part by the mass deployment of satellites, like SpaceX's Starlink, which will eventually reenter our airspace.

As more satellites and rockets are sent into orbit, and more planes take to the skies, the chances of a hit are growing, the researchers found. Even though we have the technology to track falling space debris to some extent, that's still a major concern.

"The highest-density regions, around major airports, have a 0.8 percent chance per year of being affected by an uncontrolled reentry," write the researchers in their published paper.

"This rate rises to 26 percent for larger but still busy areas of airspace, such as that found in the northeastern United States, northern Europe, or around major cities in the Asia-Pacific region."

According to The Aerospace Corporation, the likelihood of a fatal plane collision with an object falling from space was close to 1 in 100,000 in 2021.

What's more, even the smallest chunk of a rocket or satellite that's burning up could bring a plane down – making it difficult to guarantee passenger safety. Estimates suggest something as small as one gram could cause damage if it made contact with the aircraft windshield or engine.

As the chance of interference grows, so does the probability that parts of airspace will be closed – which then leads to other stretches of sky becoming more congested, or planes getting delayed or canceled altogether.

"This situation puts national authorities in a dilemma – to close airspace or not – with safety and economic implications either way," write the researchers.

Charting reentry paths for uncontrolled objects is often tricky, which means large areas of airspace need to be shut down as a precaution. We've already seen this happen, as with the Long March 5B rocket body in 2022.

There is a solution, the researchers say: those putting the objects in the sky could invest in controlled rocket reentry. While the tech for this already exists, less than 35 percent of launches currently make use of it, leaving the safety burden on the aviation industry.

Efforts continue to improve safety both inside and outside Earth's atmosphere, but they require buy-in from government agencies and private companies. It shouldn't take a disaster to force action to be taken.

"Over 2,300 rocket bodies are already in orbit and will eventually reenter in an uncontrolled manner," write the researchers. "Airspace authorities will face the challenge of uncontrolled reentries for decades to come."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.