Through a detailed analysis of the complete genomes of five cat species, researchers have been able to resolve some long-standing mysteries about the evolution of these animals – giving us a much better understanding of how different species developed.

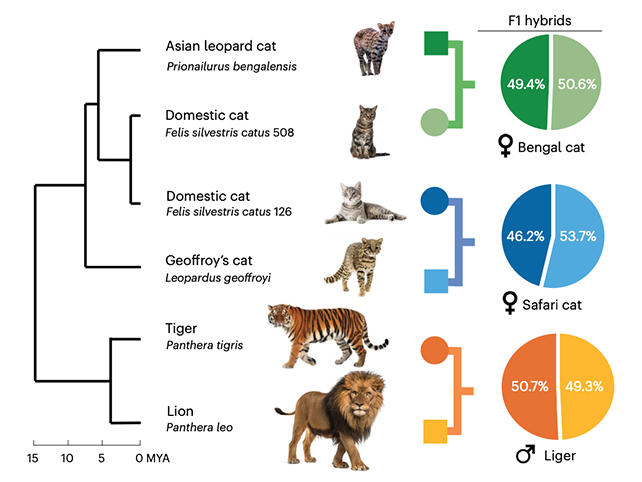

The international team of researchers looked at species including domestic cats, lions, and tigers, and used techniques such as trio binning: that's where the DNA contributed by each of an organism's parents can be sifted out and identified.

In this case, the method was applied to hybrids, allowing the researchers to distinguish specific genomes with remarkably few gaps.

"Our goal was to better understand how cats evolved and the genetic basis of the trait differences between cat species," says Bill Murphy, a zoologist at Texas A&M University.

"We wanted to take advantage of some new technologies that allow us to create more complete cat genomic maps."

One of the questions that the team was looking to answer is why cats have relatively few complex genetic variations compared to other mammals. For example, there's not much difference in the chromosomes of a lion and a domestic cat.

The new analysis suggests that it's the frequency of segmental duplications, or DNA sections very similar to other sections, that are the cause. Cats have far fewer than other mammals, which keeps their genomes more stable, and leads to fewer species.

While large genetic variations aren't as common in cats, some variations are still there, and another discovery sheds light on which parts of cat DNA are responsible for these changes – especially in terms of variations that define separate species.

The team identified a particular repetitive DNA element called DXZ4, which is what's known as a satellite repeat: affecting the 3D structure of the X chromosome, and influencing speciation. The DXZ4 segment in cats is evolving faster than 99.5 percent of the rest of the genome.

A new discovery about olfactory genes was made possible by the highly detailed genome sequences too. There's a lot of variation between species when it comes to these genes – most likely because some cat species still need a strong sense of smell, while others don't.

The study showed that species such as the fishing cat have retained the genes that help them sniff out waterborne odorants – and thus catch prey – whereas domestic cats, which don't have the same need to hunt, have lost a lot of these genes.

Taken together, the findings of the study show that where cat species are different at the genetic level, those differences really matter. That should help scientists, conservationists, and anyone working with these graceful animals.

"Our findings will open doors for people studying feline diseases, behavior, and conservation," says Murphy. "They'll be working with a more complete understanding of the genetic differences that make each type of cat unique."

The research has been published in Nature Genetics.