You've heard of the gut microbiome, and probably the vaginal microbiome: It turns out, semen can have its very own microbiome, too. Now, new research has found that it may even play a role in fertility.

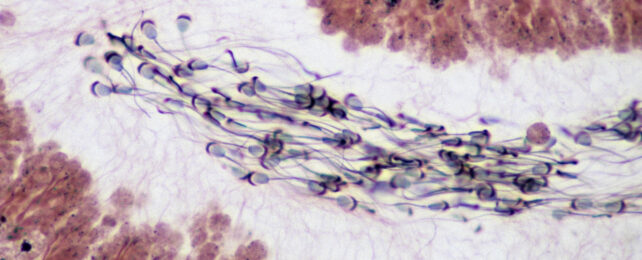

For most of its journey from the testes, sperm and its protective supply of seminal fluids do not typically contain bacteria. This changes once it passes microbially populated zones at the end of the penis, effectively picking up its own supply of flora.

A research team led by the University of California has found a link between the bacterial makeup of the semen microbiome, and the health and mobility of sperm – and therefore, the fertility of the person it comes from.

As with other microbiomes, balance among bacteria is key to healthy semen. Where that balance is tipped, the sperm seem to be sinking more than they're swimming.

The researchers analyzed semen samples from 73 cisgender men aged 18 and above, who were recruited either while looking for a fertility evaluation, or while seeking a vasectomy consultation after having already fathered children.

Semen from the 27 men with abnormal sperm motility had a higher abundance of one particular bacteria, Lactobacillus iners, compared to the 46 men whose sperm motility was normal.

Sperm is not the only reproductive fluid L. iners hangs out in. It's normal and indeed vital at certain levels in the vaginal microbiome, though too much of it can decrease fertility rates and set the scene for bacterial vaginosis, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy complications.

The researchers think L. iners could also be directly impacting male fertility. It selectively produces inflammatory L-lactic acid, which has been found to reduce sperm motility in some species. That could explain why the sperm in semen samples laden with L. iners were struggling, though it's not yet confirmed as the cause.

Three species of Pseudomonas bacteria were found in the men's semen, and all three were present regardless of whether sperm concentration was normal or abnormal. But for the 20 samples with abnormal sperm concentration, P. fluorescens and P. stutzeri were more common, while P. putida was less common, compared to the 53 samples with normal sperm counts.

This finding suggests that even closely related bacteria may not always have the same correlation with measures of fertility.

It's too early to say how all these different bacteria and the composition of the semen microbiome impact sperm and fertility, if at all. It's possible that the correlation between bacterial levels and sperm statistics is an outcome of some entirely different factor influencing them both, for instance.

While the research so far barely skims the surface of the semen microbiome, it looks to be a well of potential for fertility treatments and other seminal health issues.

"There is much more to explore regarding the microbiome and its connection to male infertility," says the study's lead author, urologist Vadim Osadchiy from the University of California.

"Our research aligns with evidence from smaller studies and will pave the way for future, more comprehensive investigations to unravel the complex relationship between the semen microbiome and fertility."

The research was published in Nature Scientific Reports.