A telescope rocketing around the Sun just beamed back the closest images and videos ever recorded of our star, but it's just getting started on its mission.

The Solar Orbiter, built by the European Space Agency (ESA) with help from NASA, flew within 48 million miles (77 million kilometers) of the Sun on June 15 – half the distance between the Sun and Earth.

That was the closest the Orbiter has gotten to the Sun since launching in February. The approach was primarily intended as a chance for the spacecraft to test its instruments – including its cameras – before it begins scientific observation in full.

But already, the orbiter discovered something new: The Sun's surface is covered in miniature solar flares – bursts of radiation that make the largest explosions in our Solar System. The scientists behind the spacecraft call these widespread flares "campfires."

"We couldn't believe it when we first saw this," Sami Solanki, a lead scientist on the Solar Probe team at the Max Planck Institute, said during a ESA webcast on Thursday.

"We started giving it crazy names like 'campfires' and 'dark fibres' and 'ghosts,'" Solanki added. "There is so much new small phenomena going on on the smaller scale that we are starting a new vocabulary to give it all names."

'This is just the beginning'

The Solar Orbiter is slated to take unprecedented measurements of the Sun's most mysterious forces over its main seven-year-long mission. However, the mission could get extended to 2030 to collect even more information.

"If it can last for 10 years, there's a good chance it will last longer," Daniel Müller, the project science for the ESA's Solar Orbiter team, said during Thursday's briefing.

Data that the probe returns could help scientists pinpoint the origins of space weather and even track eruptions on the Sun in near-real time.

The video below shows some of what the Solar Orbiter captured with its imaging instruments during this first approach.

"We are all really excited about these first images – but this is just the beginning," Müller said in a press release. "Solar Orbiter has started a grand tour of the inner Solar System, and will get much closer to the Sun within less than two years."

The spacecraft follows an oval-shaped trajectory around the Sun. All in all, it's set to complete 22 orbits, which will take it past the orbits of Mercury, Venus, and Earth before swinging it around to get its closest looks at the Sun over the next seven years.

In future approaches, the telescope will get as close as 26 million miles (42 million kilometers) to the Sun. In 2025, it will harness Venus's gravity to shift its orbit so that it can take the first-ever images of the Sun's poles.

"It's like Earth 150 years ago; nobody had been at the poles," Solanki said Thursday.

As Solar Orbiter leaves the Sun's ecliptic plane within the next couple of years, Müller said "we'll be at an angle where it starts getting interesting." In 2027, he added, the probe will get its first prime and unprecedented views of the Sun's poles.

"If we've already made some discoveries in just the first-light images, just imagine what we're going to find when we get closer to the Sun, and when we get out of the ecliptic," Holly R. Gilbert, a Solar Orbiter project scientist at NASA, said during Thursday's briefing.

'Campfires' everywhere

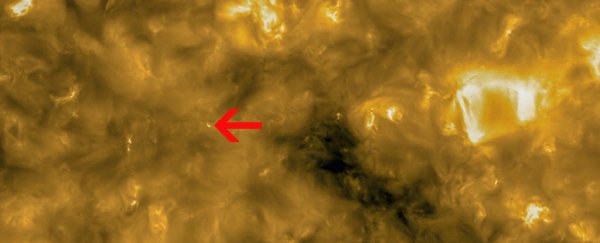

(Solar Orbiter/EUI Team/CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL/MSSL)

(Solar Orbiter/EUI Team/CSL, IAS, MPS, PMOD/WRC, ROB, UCL/MSSL)Above: A high-resolution image from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager on the Solar Orbiter spacecraft, taken May 30, 2020. The circle in the lower right corner indicates the size of Earth for scale. The arrow points to one of the ubiquitous 'campfires' on the solar surface.

Scientists have long known that solar flares exist. Telescopes have recorded images of solar eruptions as far back as 1900.

But they didn't know that the solar surface was covered in them because no telescope had been powerful enough to image them at such a high resolution.

"The campfires are little relatives of the solar flares that we can observe from Earth, million or billion times smaller," David Berghmans, who leads the team behind the high-resolution imaging instrument on the spacecraft, said in the release.

"The Sun might look quiet at the first glance, but when we look in detail, we can see those miniature flares everywhere we look."

The smallest campfire features, which are each about two pixels wide in the images (arrow in the above image), are about the size of Europe, Berghmans said Thursday.

For now, it's unclear whether these new flares are just smaller versions of the eruptions scientists have seen before, or whether they're created by an entirely different mechanism.

But the campfires could offer a clue about one of the Sun's biggest mysteries: how its corona stays so hot.

The corona is the upper atmosphere of the Sun that extends millions of miles into space. It inexplicably maintains a temperature of about 1 million degrees – far hotter than the inner layers of the star.

If the campfires produce a steady hum of explosive activity, which can accelerate particles and release enormous amounts of energy, they could produce much of that heat.

"These campfires are totally insignificant each by themselves, but summing up their effect all over the Sun, they might be the dominant contribution to the heating of the solar corona," Frédéric Auchère, who leads the imaging instrument team with Berghmans, said in the release.

What Solar Orbiter will accomplish next

One of the Solar Orbiter's primary goals over the next two years is to study solar wind: a stream of electrically charged particles that surges from the Sun and washes over the planets. The spacecraft will look for the source of this stream.

The orbiter is in its cruise phase and will eventually reach speeds as fast as the Sun's rotation, allowing it to closely track particular spots on the solar surface for an extended period of time. It will also get about 10 million miles closer to the Sun, improving the image detail and quality.

"In March 2022, we'll get into the full-blown science phase with unprecedented resolution," Müller said during Thursday's teleconference.

In that science phase, Solar Orbiter will be able to better observe solar flares and storms as they happen.

"What we want to do with Solar Orbiter is to understand how our star creates and controls the constantly changing space environment throughout the Solar System," Yannis Zouganelis, an ESA scientist working on the mission, said in January. "There are still basic mysteries about our star that remain unsolved."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: