It is a disservice to the men and women of the United States and Canadian diplomatic services to suggest they are suffering from a "mass psychogenic illness" arising from their tenure in Havana.

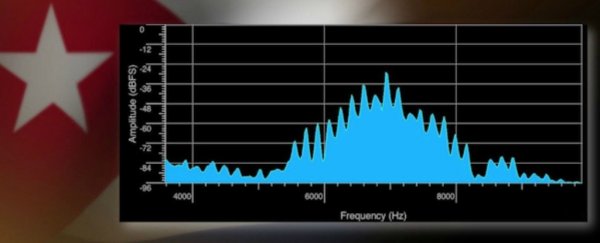

In the autumn of 2016, many members of the US mission in Cuba began to develop "symptoms of dizziness, ear pain and tinnitus" - as physicians who investigated them reported - after perceiving high frequency noise and cerebral pressure. In the late winter of 2017, 14 members of the Canadian legation began developing similar symptoms.

The mysterious "Havana syndrome" has since been a subject of intense speculation. The question is whether the victims are suffering from a psychogenic disorder arising in the mind or a somatogenic disorder arising from a physical disorder of brain tissue itself. Mass psychogenic illness is simply a new term for what used to be called "epidemic hysteria".

Do these diplomats have hysteria, now being called "Havana Syndrome"? Or do they have a lesion, caused by some kind of a device intended to inflict injury?

Victims suffered traumatic brain injuries

A number of things are wrong with the "psychogenesis" (hysteria) argument. Most notably, symptoms of hysteria are caused by the action of the mind.

A study led by Michael E Hoffer, a neuro-otologist at the University of Miami, however, reported problems with the central vestibular system (inner ear) in 36 percent of American diplomats and their families affected by Havana syndrome.

Lesions in this part of the auditory apparatus would be organic. Inner ear damage is not psychogenic and means that the tissues of the inner ear itself have sustained some kind of assault.

The affected Canadians who were evacuated to the University of Miami, and who then subsequently went to the University of Pennsylvania for similar examinations, were reportedly diagnosed with "traumatic brain injuries akin to concussions".

It is wrong to see these diplomats and their families as fitting any kind of psychogenic profile. In 1974 psychiatrist François Sirois at Laval University analyzed 70 outbreaks of "epidemic hysteria," both historical and present-day.

Of the 70, 69 occurred in girls and young women. Only one of the 70 - the koro epidemic in Singapore in the 1960s - affected males only. (Koro is the delusional belief that your sex organs are retracting inside your body.)

Historically, "hysteria" - meaning physical symptoms "of unexplained origin" - was associated more with women than men. This is because it has been women who, traditionally, have borne the brunt of loss and suffering, and often dealt with these wrenching emotions by developing bodily symptoms.

Thinking that these middle-aged men and women in the US and Canadian embassies in Havana could have been suffering from "mass psychogenic illness" simply defies belief.

Endometriosis once diagnosed as hysteria

It is wrong to imagine that their symptoms could have some kind of psychological mechanism. The mechanism of psychogenesis/hysteria is suggestion. For example, all the schoolgirls fall to the ground vomiting at recess because they have been suggested into their symptoms.

The loss of balance, sensations of pressure inside their brains and so forth that these diplomats report are no more psychological than mumps.

"Stress" has been invoked as the psychological motor. Indeed these diplomats and their families are under stress.

But so is everyone else. Stress is a constant in modern life. Schoolteachers in inner city schools around the globe are also under stress, but they don't develop this illness of the diplomats.

What caused these lesions? It is anybody's guess. But medicine has a long history of assuming psychogenesis when occult organic disease is at play. Multiple sclerosis in women, for example was once considered to be a form of hysteria.

Similarly, before the discovery of endometriosis, deep pelvic pain in women was diagnosed as hysteria. Let's not make this mistake again. ![]()

Edward Shorter, Jason A Hannah Professor of the History of Medicine, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Toronto.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Opinions expressed in this article don't necessarily reflect the views of ScienceAlert editorial staff.