The star Betelgeuse visibly dimmed in 2019. Now, a new analysis reveals why: Betelgeuse blew out and is still recovering.

The red supergiant star, which is about 530 light-years from Earth, is among the brightest in the night sky. The star forms the shoulder of the constellation Orion (The Hunter).

It's also geriatric: Betelgeuse is nearing the end of its stellar life and will eventually explode in a supernova visible from Earth, though it might take another 100,000 years, according to 2021 research.

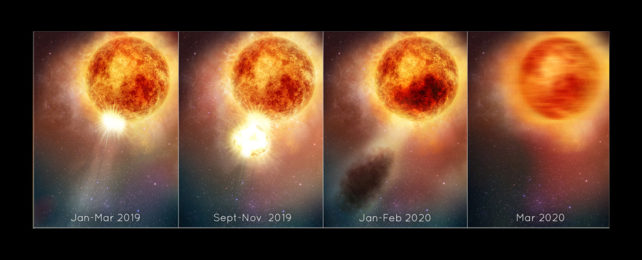

In late 2019, Betelgeuse's light started to dim. By February 2020, it had lost two-thirds of its normal luminosity as seen from Earth.

Scientists studying the bizarre dimming concluded that the star itself was not imminently going supernova but that a giant dust cloud had obscured some of the star's light.

Related: Bright star Betelgeuse might be harboring a deep, dark secret

Now, scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed that this dust cloud was the result of an enormous ejection from the star's surface: A plume more than 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) across may have risen from inside the star, producing the equivalent of a starquake, a shock that blew out a chunk of the star's surface 400 million times larger than those usually seen in the sun's coronal mass ejections, the team reported in a paper published to the preprint database arXiv and accepted by The Astrophysical Journal for publication.

"Betelgeuse continues doing some very unusual things right now; the interior is sort of bouncing," study author Andrea Dupree, associate director of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a statement.

This is uncharted territory in star science, Dupree said.

"We've never before seen a huge mass ejection of the surface of a star," she said. "We are left with something going on that we don't completely understand. It's a totally new phenomenon that we can observe directly and resolve surface details with Hubble. We're watching stellar evolution in real time."

The new research also incorporated information from a variety of other stellar observatories, such as the STELLA Robotic Observatory in Spain's Canary Islands, and NASA's Earth-orbiting STEREO-A spacecraft.

By piecing together different types of data, Dupree and her team were able to put together a narrative of the blowout and its aftermath.

The eruption blew off a chunk of the star's lower atmosphere, the photosphere, leaving behind a cool spot that was further occluded by the dust cloud from the blowout.

Above: In the first two panels, as seen in ultraviolet light with the Hubble Space Telescope, a bright, hot blob of plasma is ejected from the emergence of a huge convection cell on the star's surface. In panel three, the outflowing, expelled gas rapidly expands outward. It cools to form an enormous cloud of obscuring dust grains. The final panel reveals the huge dust cloud blocking the light (as seen from Earth) from a quarter of the star's surface.

The chunk of photosphere was several times the mass of Earth's moon, according to NASA's statement.

This cool spot and dust cloud explain why Betelgeuse's light dimmed. The star is still feeling the reverberations, the researchers found.

Before the eruption, Betelgeuse had a pulsating pattern, dimming and brightening on a 400-day cycle. That cycle is now gone, at least temporarily.

It's possible that the convection cells inside the star are still sloshing around, disrupting this pattern, the researchers found.

The star's outer atmosphere may be back to normal, but its surface may still be jiggling like Jell-O, according to NASA's Hubblesite.

The eruption isn't evidence that Betelgeuse will go supernova anytime soon, the researchers said, but it does show how old stars lose mass.

If Betelgeuse does finally die in a stellar explosion, the light will be visible in the daytime from Earth, but the star is too far away to have any other impacts on our planet.

Related content:

Red supergiants 'dance' because they have too much gas

15 unforgettable images of stars

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.