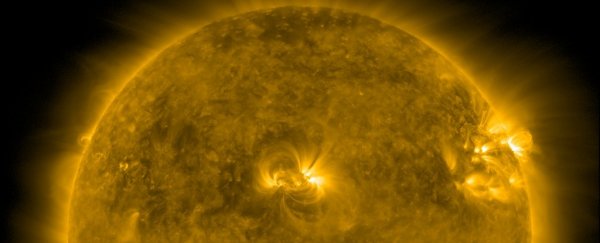

The Sun appears to be waking up from the quiet period of its 11-year cycle.

On 3 July 2021, at 14:29 UTC (10:29 EDT), our wild star spat out its first X-class flare of Solar Cycle 25; it was the most powerful flare we've seen since September 2017.

X-class flares are among the most powerful solar eruptions from our host star, with the mightiest on record being an astonishing X28 in November 2003.

This new flare wasn't quite so intense, clocking in at X1.5 - but, even so, it produced a pulse of X-rays that hit the upper atmosphere and managed to cause a shortwave radio blackout over the Atlantic Ocean.

The most recent X-class flare, prior to this new one, took place in September 2017, when the Sun erupted in an X8.2 flare.

It's a sign, along with an increase in coronal loops of plasma arcing up from the Sun's surface, that the cycle is definitely becoming more active.

Although the Sun seems pretty consistent from our day-to-day perspective here on Earth, a long-term view reveals dynamic activity. Part of that is the solar cycle.

This is based on the Sun's magnetic field, which flips around every 11 years, north and south magnetic poles switching places. It's not known what drives these cycles, but we do know that the poles switch during solar maximum, when the polar magnetic field is at its weakest.

Because the Sun's magnetic field controls its activity – such as sunspots (temporary regions of strong magnetic fields), solar flares, and coronal mass ejections (produced by magnetic field lines snapping and reconnecting) – when magnetic fields are weak across the Sun's surface, the period of minimal activity is called the solar minimum.

Once the poles have switched, the magnetic field weakens, and solar activity decreases, before rising again ahead of the next polar switch. The most recent solar minimum took place in December 2019, so, over the coming months and years, we should expect to see the Sun getting more rowdy, peaking at maximum in around July 2025.

Not all solar maxima are created equal, so it's not entirely clear whether we will have a weak or powerful cycle. The average sunspot count for a maximum is 179; Solar Cycle 24 peaked at only 114. NASA and the NOAA have predicted Solar Cycle 25 will be similar, with a peak of 115 sunspots, but other scientists have predicted quite the opposite - one of the strongest solar maxima ever recorded.

Interestingly, it took nearly twice as long for the first X-class flare to appear in Solar Cycle 24. If that is significant, we won't know until after the solar maximum for Solar Cycle 25.

So what does this mean for Earth? Well, if a solar flare or coronal mass ejection blasts out in the direction of Earth, we can see a few effects. There's no danger from radiation to us humans scrambling about on the surface - our atmosphere protects us.

But for more powerful flares - like the one of 3 July - and weaker, M-class flares, we can see some disruptions to the atmospheric layers where communications signals travel. This means radio communications and navigation systems can be affected. For the most extreme events, power grids may be knocked offline, although that happens incredibly rarely.

Material from the Sun can also trigger auroras here on Earth, as particles interact with gases in our planet's atmosphere to produce the glowing phenomenon.

The sunspot that produced the flare, named 2838, developed overnight out of nowhere, and was also responsible for an M2 flare. It has since rotated away out of view to the far side of the Sun, where it may still be active. We'll have to wait a few days to see if it rotates back.