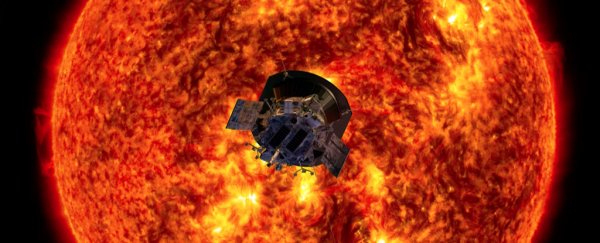

NASA's Parker Solar Probe made the closest ever flyby of the Sun in August 2018, collecting massive amounts of data using cutting-edge scientific instruments from a distance of 15 million miles - a mission that also, incidentally, set the record for the fastest-ever human-made object of all time.

Now, scientists are starting to release what they learned from the data it collected. Four new papers published in the journal Nature on Wednesday reveal new findings that could rewrite the way we understand the way stars are born, evolve, and die.

They could also help us find new ways to protect astronauts from harsh space weather during long distance trips through the Solar System.

"The complexity was mind-blowing when we first started looking at the data," said Stuart Bale, lead researcher for the probe's onboard instrument suite at the University of California, Berkeley.

"Now, I've gotten used to it. But when I show colleagues for the first time, they're just blown away."

The most startling discovery the teams made was that magnetic fields emanating from our star seemed to unexpectedly flip back and forth, causing local disturbances - what scientists dubbed "switchbacks" - which can even cause them to point back at the Sun at times.

The cause of these switchbacks is still a mystery to scientists, but they could eventually allow us to understand how energy flows away from the Sun and throughout the Solar System.

"Waves have been seen in the solar wind from the start of the space age, and we assumed that closer to the Sun the waves would get stronger, but we were not expecting to see them organize into these coherent structured velocity spikes," said Justin Kasper, principal investigator at the University of Michigan said in a statement.

The scientists also found that the Sun's radiation vaporizes cosmic dust particles around itself, leaving a 3.5 million mile (5.6 million kilometre) dust-free zone.

They also found that solar winds rotate around the Sun at speeds "nearly ten times larger than predicted by the standard models," according to Kasper.

The mission also marks the first time that solar wind flows were observed still rotating around the Sun, rather than shooting off at a perpendicular velocity from the star - the kind of straight trajectories we observe from Earth.

"The Sun is the only star we can examine this closely," Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters, said in the statement.

"Getting data at the source is already revolutionizing our understanding of our own star and stars across the universe. Our little spacecraft is soldiering through brutal conditions to send home startling and exciting revelations."

The probe will be attempting to get even closer to the Sun during an encounter on January 29, 2020.

This article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.