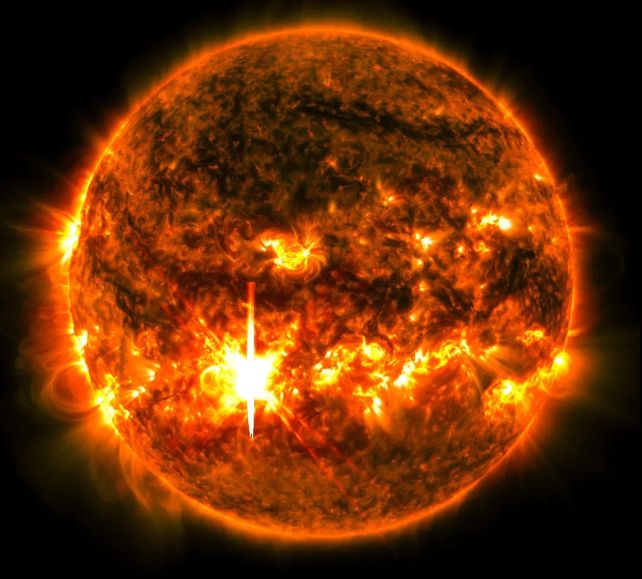

The Sun has started spooky season with a bang, letting loose on October 1 with a colossal flare and coronal mass ejection headed right for Earth.

The flare clocked in at X7.1 – the second most powerful flare of the current solar cycle, and one of the most powerful solar flares ever measured, sitting within the top 30 flares over the last 30 years.

We're not in any danger, but the NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center has forecast minor to strong geomagnetic storms over the next few days, from 3 to 5 October, as we await the gust of solar particles as the coronal mass ejection blasts through the Solar System.

Solar flares and coronal mass ejections are normal behavior for the Sun, particularly when it's in the peak of its activity cycle, as scientists believe is the case right now. They often occur in association with each other, erupting from sunspots on the surface of the Sun.

These sunspots are regions where the solar magnetic field is temporarily stronger than the magnetic fields everywhere else on the Sun. When sunspot magnetic fields of opposite polarity get tangled, they can snap and reconnect, causing powerful explosions of energy. A solar flare is an eruption of light; that reaches us at light speed and can cause temporary radio blackouts.

A coronal mass ejection (CME) is the ejection of, well, coronal mass: billions of tons of solar particles, tangled up with magnetic fields, are belched out into space, where they rocket across the Solar System.

When these solar particles collide with Earth's magnetosphere, the result is what we call a geomagnetic storm, a major disruption of Earth's magnetosphere that mostly affects the upper atmosphere, far from where it would affect most humans.

In addition, solar particles can be diverted and accelerated along the magnetic field lines to higher latitudes, where they are dumped out into the atmosphere. They interact with particles in Earth's atmosphere, the ionization of which creates colorful, dancing lights in the sky – the auroras borealis and australis.

The X7.1 flare and associated CME came from a particularly complex sunspot region named AR 3842. This collection of sunspots is what is known as a Beta-Gamma-Delta region. It contains a complicated tangle of magnetic field lines of opposite polarity, all very close together – the optimum conditions for flare activity.

M3.2 flare from 13842 about 30 min ago. Hopefully the sunspot group has more oomph left as it is about as Earth-directed as it will ever be. pic.twitter.com/L2HzfPheuL

— Jure Atanackov (@JAtanackov) October 2, 2024

AR 3842 is currently traversing the solar disk and is right in the middle of our field of view; prime position for Earth-directed eruptions. And it emitted another M-class flare just a few hours ago, at time of writing, clocking in at M3.3.

Flares of these levels are pretty spectacular, and can cause some disruptions to life on Earth. They can cause high-frequency radio blackouts on the sunlit side of Earth.

Coronal mass ejections are potentially more disruptive, but the strength of those varies according to a number of factors, and there's no sign that the AR 3842 CME is going to be anything to worry about.

The most powerful solar flare from the current solar cycle was an X8.7 that we saw back in May.

The sunspot region associated with that flare brought some of the most stunning auroras the world has ever seen; it's unclear whether the performance will be repeated, but the forecasts suggest that we're going to get at least something of a lightshow.

The NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center, the British Met Office's Space Weather service, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology are all forecasting G3-level – or strong – geomagnetic storms, with a chance of aurora.

According to Space Weather Live, the forecast for the nights of 4 and 5 is predicted to peak at over 6 and 7 respectively on the 10-point Kp Index of geomagnetic activity, that can be used as a proxy for aurora predictions.

It's been a bumper year for auroras so far. Let's hope there's many more to see yet.