In just a few days, the Moon will turn a shade of rust and loom larger in the sky than usual in a relatively rare astronomical event.

For the half of the planet fortunate enough to see it, it's a chance to see two fascinating spectacles combined in what's known as a 'super blood moon' eclipse (not a very scientific name, we'll get to that in a bit).

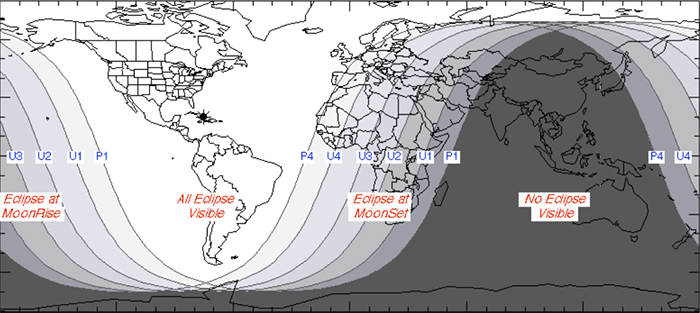

If you find yourself anywhere on the American continents, you're in for a real treat on January 20. So long as your skies are cloud free roughly 10:15 pm to 1:45 am EST (03:15 to 06:45 UTC), you'll see an orange hue creep across the face of the full Moon.

Those in Western Europe and Africa should see at least some of the display with the rising or setting of the Moon. If you're in the Pacific over the date line, mark down January 21.

(NASA)

(NASA)

Not all of us have the patience to watch the entire 3.5 hour transformation, in which case simply step outside at about midnight EST (05:15 UTC January 21) to see the climax.

If you're in Asia and Australasia, don't even think about complaining. You had your chance to see it this earlier this year. And it wasn't just a super blood moon then, either. It was a super blue blood moon.

Ignoring its Halloween-worthy title, the blood moon's sunset hues are caused by the scattering and refracting of sunlight through our atmosphere as the Moon passes through Earth's shadow during a total lunar eclipse.

Lunar eclipses are pretty to look at, but they aren't exactly uncommon - between two and five lunar eclipses happen each year, so we can expect to see a few in our lifetime. (A rather spectacular one was snapped from the International Space Station earlier this year, for example.)

That said, this one isn't just any eclipse. Our planet's shiny companion will be at its perigee, meaning the Moon will be at its closest point to Earth in its orbit. For night owls who love to lose themselves in a beautiful moment, this is well worth stepping outside for.

But no matter how you feel about the event itself, not everybody is in love with the name. Super Blood Moon sounds a bit like a b-grade Hollywood movie title, begging for a sequel 'Super Blood Moon II: Second Blood'.

More importantly, the complex cultural history of the name risks confusing the science.

Like it or not, the term has been around for centuries, as have myths and legends surrounding its effects. Humans have been fascinated and afraid of eclipses since forever, and with its reddish glow the lunar eclipse is begging to be described as bloody.

Yet it was only recently that the term was given a boost by two Christian pastors, referring not to the eclipse's colour, but to the eclipsing of four consecutive full-moons.

In a 2013 book titled Four Blood Moons, they wrote of a prophecy foretelling of end times coinciding with this tetrad of astronomical events. Uh, sure.

As for the term supermoon, it's also a term with less than scientific origins. Around forty years ago, astrologer named Richard Nollelle came up with the description, claiming that an ultra-close Moon could impact the weather.

But the Moon is just two percent closer at this point, so while the name makes it sound exciting, you might be disappointed when it doesn't suddenly loom massive on the horizon.

While the full moon at perigee does pull a little on the tides, this extra dose of gravity isn't as strong as that of a new moon (which combines with the Sun's pull) in a similar position. Which also isn't much.

So forget weather. Or earthquakes for that matter. The supermoon isn't all that super.

Should we be using the terms at all? Sure, scientists bristle at their pseudoscientific origins. But they're certainly more exciting than "total lunar eclipse combined with a full moon perigee".

Whichever side of the fence you sit on, the astronomical horse has bolted. Language has a habit of doing its own thing, so sometimes we can only make sure the science part is sound.

The next lunar eclipse to cast its crimson glow over the planet won't be until May, 2021. At least we can postpone the debate for a couple of years.

A first version of this article was originally published in December 2018.