The strange asteroid responsible for Earth's annual shower of Geminid meteors just got even more peculiar.

Every orbit, as it approaches the Sun and heats up, 3200 Phaethon grows a comet-like tail of material, which streams away in a pale fog.

Phaethon's tail was thought to consist of tiny grains of dust, but new observations reveal that's not the case. Rather, the asteroid belches out sodium gas – just like the planet Mercury, but smaller.

It's a finding that significantly changes our understanding of this strange object, as well as other tailed rocks that skim close to the Sun, suggesting that what we think are comets may, in at least some cases, truly be sodium-spewing asteroids.

"Our analysis shows that Phaethon's comet-like activity cannot be explained by any kind of dust," says astrophysicist Qicheng Zhang of the California Institute of Technology.

Comets and asteroids are two distinct classes of objects, and it used to be fairly easy to tell them apart. When comets approach the Sun, they brighten, and the ice bound up in the rock sublimates, loosening dust as it does so. The gas of the sublimated ice and the dust form twin tails that stream away from the Sun at slightly different angles.

Asteroids have little or no ice, and therefore were thought not to have tails. However, in recent years, astronomers have found a growing number of asteroids with comet-like characteristics, including a tail. These are known as active asteroids, and their discovery blurs the line between how objects in our Solar System behave.

In fact, Phaethon has always been regarded as a bit of an oddball ever since its discovery in the 1980s, and scientists realized its 524-day orbit matched up with the appearance of the Geminids in our night sky. Comets are usually the objects responsible for Earth's meteor showers, too: when Earth passes through the debris left behind by a comet, that debris burns up as it falls into our atmosphere, creating a glorious light show.

One of the problems with the dust hypothesis explaining Phaethon's tail is that the dust production was insufficient to explain the amount of material required to produce the Geminids. So researchers went looking to see if there were other explanations.

"Comets often glow brilliantly by sodium emission when very near the Sun, so we suspected sodium could likewise serve a key role in Phaethon's brightening," Zhang says.

Two years ago, modeling and experiment work suggested that Phaethon's tail might also be sodium that sublimates when the asteroid approaches the Sun. The next step was to prove it.

The research team collected data from two solar observatories, NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) and the joint ESA NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). At first, STEREO wasn't able to detect the wavelengths in which sodium fluoresces. Luckily, as the spacecraft aged, its Heliospheric Imager 1 filter has degraded to increase sensitivity to sodium.

The team combed through data collected by these spacecraft and found the tail appeared during 18 of Phaethon's close approaches to the Sun between 1997 and 2022.

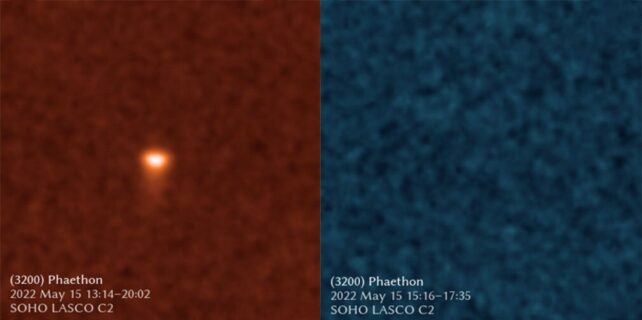

The SOHO observations turned out to be the kicker, though. The spacecraft is equipped with different filters that can detect dust and sodium. Phaethon's tail appeared in images taken with the sodium-sensitive filter… but not images taken with the dust-sensitive filter. Moreover, the shape of the tail matched predictions of a sodium tail, not a dust one.

This suggests that the tail is indeed predominantly sodium gas, which means we may have been looking at some other Solar System objects incorrectly, too.

"A lot of those other sunskirting 'comets' may also not be 'comets' in the usual, icy body sense, but may instead be rocky asteroids like Phaethon heated up by the Sun," Zhang says.

So that's one mystery potentially solved, but it still leaves the problem of the Geminids. If Phaethon is ejecting gas, not dust, that makes the shower of meteors even harder to explain. It's possible, however, that an event buried in time could be responsible. Perhaps a piece of Phaethon broke free, leaving a massive debris cloud through which Earth moves every year, for instance.

Another is Phaethon's rotation rate. Scientists recently found that the asteroid's spin is increasing at a rate of 4 milliseconds per year, which is really unusual for an asteroid. Cometary outgassing increases the spin rate of comets, but Zhang and his team found that Phaethon's sodium outgassing rate is insufficient to explain its spin acceleration.

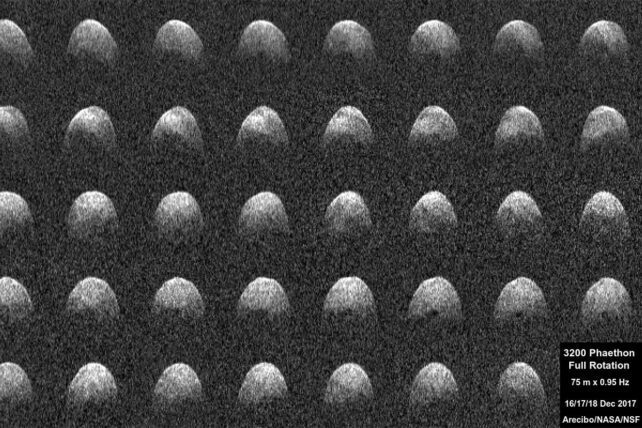

So never fear. There are still plenty of riddles remaining in Phaethon's weird potato body.

"Future investigations extending our findings with more sophisticated thermophysical and dynamical modeling of Phaethon and the Geminids stream may provide more detailed insight into the mechanics of Phaethon's sodium activity and its role, if any, in the still enigmatic Geminids formation process," the researchers write.

The findings have been published in The Planetary Science Journal.