A buzz of clicks and gleeful victory squeals compose the soundtrack in our first ever footage from the perspective of dolphins freely hunting off the coast of North America.

The US Navy strapped cameras to their dolphins, which are trained to help identify undersea mines and protect some of America's nuclear stockpile, then gave them free rein to hunt in San Diego Bay.

The clever marine mammals did not disappoint, offering up exciting chases and even targeting venomous sea snakes to the surprise of the researchers.

For such popular, well-known animals, there are still so many basic things we don't yet know about these highly social and often gross cetaceans, like precisely how they typically feed.

Researchers broadly know of at least two techniques: slurping up prey like noodles from a bowl, and ramming them down like a hot dog between rides at a state fair.

But the footage has revealed a whole lot more.

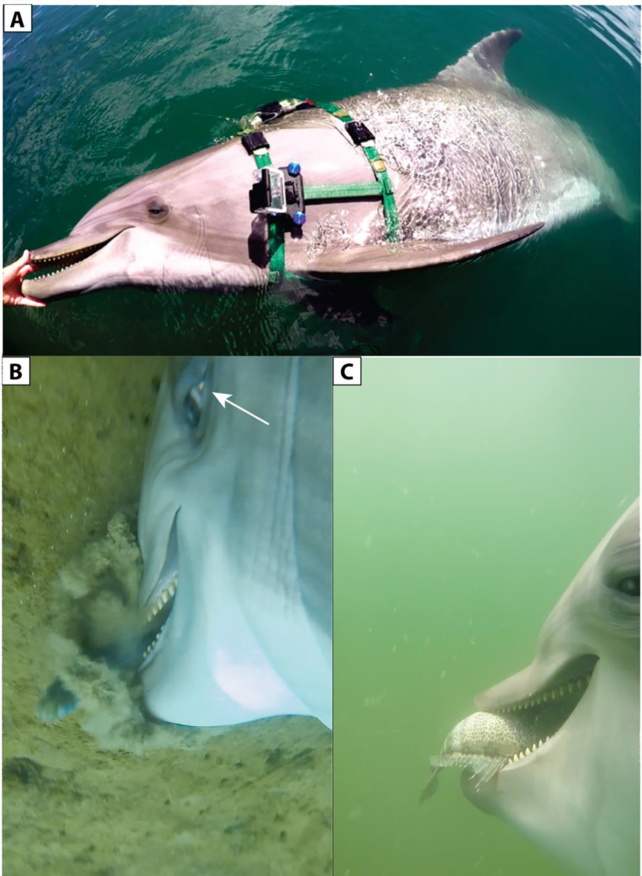

The cameras, strapped to six bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the US National Marine Mammal Foundation (NMMF), recorded six months of footage and audio – providing us with new insights into these mammals' hunting strategies and communications.

The recording equipment was placed on their backs or sides, displaying disturbingly odd angles of their eyes and mouths.

While these dolphins aren't wild, they are provided with regular opportunities to hunt in the open ocean, complementing their usual diet of frozen fish. So it is likely these animals use similar methods to their wild brethren, the NMMF marine mammal veterinarian Sam Ridgway and colleagues explain.

"As dolphins hunted, they clicked almost constantly at intervals of 20 to 50 milliseconds," they write. "On approaching prey, click intervals shorten into a terminal buzz and then a squeal. On contact with fish, buzzing and squealing was almost constant until after the fish was swallowed."

The camera-strapped dolphins caught more than 200 fish, including bass, croakers, halibut, smelt and pipefish. The smelt often flung themselves into the air in desperate attempts to escape the skilful predators.

But the dolphins tracked their every move, swimming upside down to give their swiveling eyes a clear view – a technique also observed previously in wild dolphins.

"These dolphins appeared to use both sight and sound to find prey," Ridgway and colleagues write. "At distance, the dolphins always used echolocation to find fish. Up close, vision and echolocation appeared to be used together."

The cameras also recorded the sound of the animals' hearts as they pumped hard to keep up with the strenuous activities, and revealed that rather than ramming their victims down, the dolphins instead used suction to help gulp down their still struggling prey with impressively strong throat muscles.

The dolphins mostly sucked fish in from the sides of their open mouths, throat muscles expanded and tongue withdrawn out of the way. The expanded inner mouth space helps create negative pressure that their sucking muscles add to.

While dolphins have been caught messing around with snakes before, including river dolphins playing with an absurdly large anaconda, the footage confirmed for the first time that they may also eat these reptiles too.

One dolphin consumed eight highly venomous yellow-bellied sea snakes (Hydrophis platurus).

"Our dolphin displayed no signs of illness after consuming the small snakes," the researchers write, but they acknowledge this could also be unusual behavior since the dolphins are captive animals.

"Perhaps the dolphin's lack of experience in feeding with dolphin groups in the wild led to the consumption of this outlier prey."

The lead author of the study, Sam Ridgway, recently passed away at age 86, leaving behind a rich legacy of research.

"His creative approach to partnering with Navy dolphins to better understand the species' behavior, anatomy, health, sonar, and communication will continue to educate and inspire future scientists for generations," NMMF ethologist Brittany Jones told The Guardian.

As for the navy-trained dolphins, they "work in open water almost every day," NMMF explains on their website. "They can swim away if they choose, and over the years a few have. But almost all stay."

This research was published in PLOS ONE.