The bright, white tail feathers of the otherwise inconspicuous Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) are the most reflective on record.

An international team of researchers found that the woodcock's white patches reflected up to 55 percent of light, making their feathers around 30 percent more reflective than any other bird previously measured.

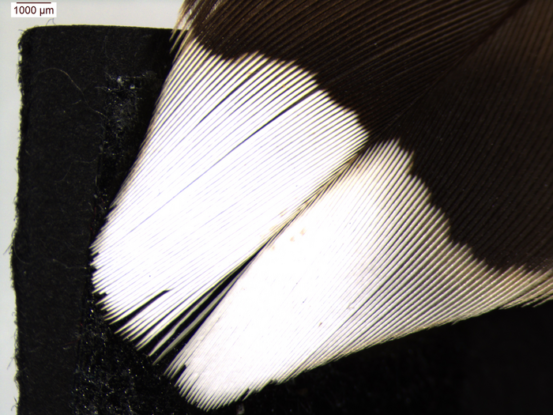

Woodcocks are mottled brown birds with white patches on their tail feathers' undersides.

Around spring in Europe and Asia, males use these bright patches in breeding display flights to catch the eye of females on the ground, and females fan out their tail feathers to attract males flying overhead.

This mating ritual happens at dusk or dawn when the woodcock is most active.

Most other times, the white patches are hidden under speckled brown feathers. These feathers blend into the leaf litter so the woodcock can poke around for earthworms and insects without attracting predators.

"Bird enthusiasts have long known that woodcocks have these intense, white patches," said lead researcher and Imperial College London ornithologist Jamie Dunning.

"From an ecological perspective, the intensity of the reflectance from these feathers makes sense – they need to hoover up all the light available in a very dimly lit environment, under the woodland canopy at night."

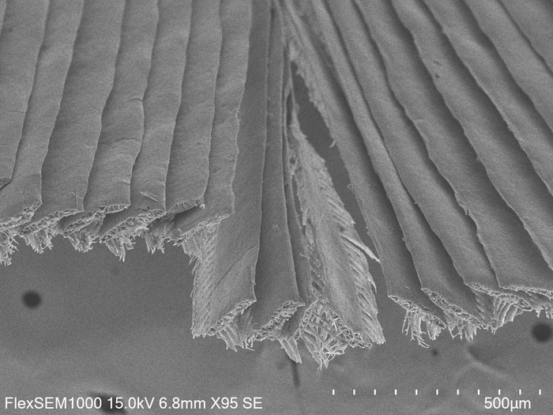

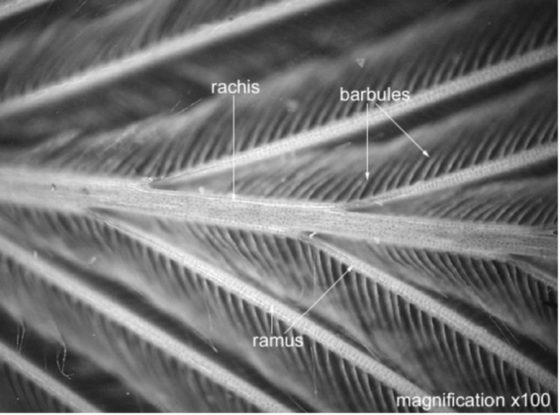

Researchers sourced tail feathers from a collection in Switzerland to find out just how bright the woodcock's feathers were. They used electron microscopy to analyze the structure, spectrophotometry to measure light reflectance, and optical modeling to track how light interacted with structures inside the feather.

After comparing the results to those of other species, researchers reported that the woodcock had "the whitest white plumage patch currently known among the birds".

The woodcock's white patches reflected up to 55 percent of light. This was 31 percent brighter than the closest comparator, the Caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia), which reflected up to 38 percent of light.

Macro and microscopic structures were responsible for this brilliant, reflective effect.

Within a single feather, the branches, called rami, were flattened and overlapped each other like Venetian blinds.

This increased the surface area available for reflection and prevented light from traveling through the cracks between branches.

The thickened branches of feathers (rami) were better at scattering light in many directions because they comprised a network of keratin nanofibers and air pockets.

All this came together to produce the whitest of white feathers, which the woodcock uses to communicate in dimly lit environments.

This paper was published in the Royal Society Interface.