Most of the strategies we hear about when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions involve figuring out ways to pump less carbon into the air, whether by shifting our reliance on coal-based electricity to clean energy sources, driving electric or hydrogen fuel cell cars, or lessening our impact on the atmosphere through cleaner agricultural processes.

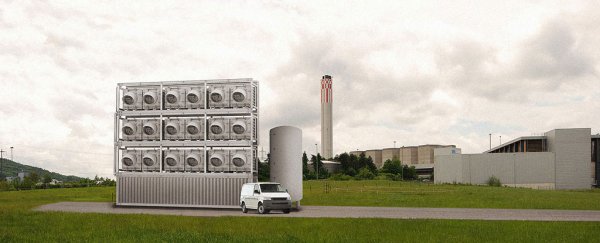

But what about the greenhouse gases that are already trapping heat in the atmosphere? To do something about them, you're looking at carbon capture and storage, a relatively new kind of technology that aims to suck carbon pollution directly out of the air around us. And the world's first commercial carbon capture plant is set to open later this year, with Swiss company Climeworks building a facility near Zurich.

Expected to start operating in September or October, Climeworks' pilot plant will not only draw and filter carbon dioxide (CO2) out of ambient air – it will then repurpose the accumulated carbon as a marketable product.

The company is looking at selling its CO2 to third parties – such as a nearby greenhouse for use in agricultural processes like growing vegetables – but it has also considered other partners, such as offloading the CO2 to beverage makers that could use it to carbonate drinks.

The process Climeworks uses is called direct air capture, where collector modules suck air into a sponge-like filter treated with chemicals derived from ammonia. This filter binds gaseous CO2, which can then be released through heating.

Once the Zurich plant is up and running later in the year, Climeworks hopes to extract somewhere between 2 and 3 tonnes of C02 from the atmosphere daily. That sounds like a lot, but it only adds up to the equivalent emissions of about 200 cars annually (900 tonnes), and is a drop in the ocean compared to the 40 billion tonnes or so of carbon humans put into the atmosphere every year. This means Climeworks' strategy will only make a serious impact if the technology rolls out at a significant scale.

One of the advantages of the system is that direct air capture plants or modules can be set up anywhere. "The advantage of taking it out of the ambient air is that you can do it wherever you are on the planet," Climeworks' chief operating officer Dominique Kronenberg told Richard Schiffman at New Scientist. "You don't depend on a C02 source, so you don't have high costs transporting it where it is needed."

But to truly scale, carbon capture will have to be economical, and right now the biggest catch might its be price. At around US$600 per tonne, Climeworks' system isn't an inexpensive way of reducing CO2 in the atmosphere, and this is the key factor that makes critics think carbon capture might be more of an illusion than a realistic strategy to fight climate change.

"I think it provides false hope," engineer Howard Herzog from MIT's Energy Initiative told New Scientist.

Seeing as it has taken decades for consumers and the industry at large to get behind clean energy options such as solar, wind, and hydro power, Herzog asks "Why should we expect future generations to adopt significantly more expensive measures to deal with C02?"

But despite the questions some have over carbon capture, there's no denying that there's a lot of interest in the potential of the technology, with Canada's Carbon Engineering and New York-based Global Thermostat also working on implementing direct air capture plants.

"While there is no one silver bullet technology to end climate change, using direct air capture to make fuels is potentially scalable, in a way that biofuels aren't, because it doesn't use much land or other resources," Carbon Engineering founder David Keith told New Scientist.

We'll have to wait and see how Climeworks' prototype facility pans out later this year, and let's hope this ambitious technology has something substantive to add world carbon reduction efforts. One thing's for sure, with noticeable evidence of climate change becoming clearer all the time, we need as many real solutions as we can get right now.