It's a place that almost seems too magical to exist: the world's largest underwater cave, spanning an incredible 347 kilometres (216 miles) of subterranean caverns, discovered in Mexico a month ago.

When archaeologists unveiled this immense, immersed labyrinth, they said it wasn't just a natural wonder, but an important archaeological find set to reveal sunken secrets of the ancient Maya civilisation – and already that promise is holding true.

Unveiling their preliminary findings this week, a research team led by underwater archaeologist Guillermo de Anda from Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History said the sprawling cave consists of almost 250 cenotes (naturally occurring sinkholes) and hosts 198 archaeological sites, some 140 of which are Maya in origin.

(GAM/INAH)

(GAM/INAH)

"This undoubtedly makes it the most important submerged archaeological site in the world," de Anda says.

"Another important feature is the amount of archaeological elements that are there and the level of preservation they contain."

Among the finds the divers have already uncovered are human remains, including skeletons and seemingly burnt human bones, that are at least 9,000 years old – suggesting human activity in the eastern Mexican region goes back thousands of years earlier than researchers thought, possibly as part of an ancient Maya trade route.

"The merchants followed established routes and used these places as ritual pilgrimage points, they made stops at altars and sacred sites to make an exchange with the gods and they've left their mark there," de Anda told media at a press conference.

De Anda, who leads the Great Maya Aquifer Project (GAM), suggests people probably didn't actually live in the branching underwater cave – called the Sac Actun System – but ventured inside it during periods of great climate stress to search for water.

(GAM/INAH)

(GAM/INAH)

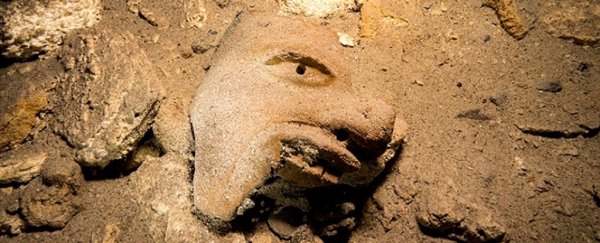

But their culture and the caves were nonetheless inextricably linked, with the divers finding numerous examples of Maya-era pottery and other ceramics such as wall etchings, but also evidence of larger artefacts, such as a shrine to the Maya god of commerce and a staircase structure inside one cenote.

When they didn't have staircases, descending into the world's largest underwater cave could be dangerous – the amount of bones the cavern holds suggests not everybody was able to climb back out again, and the same fate may have been true for many animals.

(GAM/INAH)

(GAM/INAH)

Inside the cave, researchers found fossils of numerous creatures from the last Ice Age, including giant sloths and bears, as well as the remains of an extinct elephant-like animal called a gomphothere.

Amidst the excitement over this bevy of early discoveries comes a warning from the researchers, who caution the archaeological site is already imperiled by human activity – both from tourists who enter the cenotes to snorkel and swim, and also pollution: a major highway runs over much of the cave, which is also close to an open-air dump.

If those threats can be contained, there's no telling what we could learn from this "enormous octopus" of a cave, which, as the researchers explain, could become even bigger – if divers can successfully link it to other branching underwater caverns nearby.

(GAM/INAH)

(GAM/INAH)

"There are other caves around Sac Actun that might be connected," said one of the team, GAM's chief of underwater exploration, Robert Schmittner.

"We're already close to the next one and they're probably linked. That other one is 18 kilometres (11 miles) long and is called 'The Mother of all Cenotes' … If so, the cave system would be longer than 500 kilometres, and it seems to have no end."