Beneath the cyan and cerulean waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands lurks a leviathan. Its true extent has been hidden for many years, but no more. What geologists have found is a marvel - the biggest, hottest known volcano in the world.

Startlingly, it's more than twice the size of the previous record holder, Mauna Loa on the Island of Hawai'i. And it could change our understanding of the vast Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain of volcanoes that span the North Pacific Ocean.

The new record-breaker spreads across around 148,000 cubic kilometres (35,507 cubic miles) beneath the waves of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, compared to Mauna Loa's 74,000.

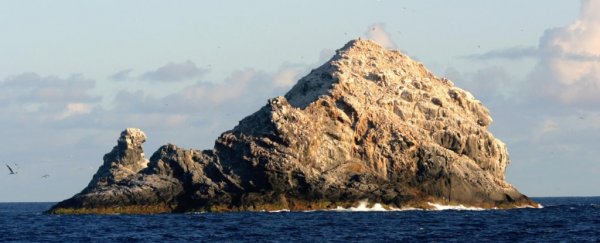

Only relatively small rocky pinnacles known as the Gardner Pinnacles break the surface, giving the volcano its name - Pūhāhonu, the Hawai'ian word for 'turtle rising for breath'.

"We are sharing with the science community and the public that we should be calling this volcano by the name the Hawaiians have given to it, rather than the western name for the two rocky small islands that are the only above sea level remnants of this once majestic volcano," said geologist Michael Garcia of the University of Hawai'i at Manoa.

Back in the 1970s, low-resolution bathymetric data suggested Pūhāhonu was around 54,000 cubic kilometres in size, then thought to be the largest volcano before a more extensive survey of Mauna Loa revealed its true size.

Pūhāhonu only regains its crown after extensive surveys of the region added high-resolution bathymetric and multibeam sonar data to our existing understanding of the northwest Hawaiian Ridge, from which the volcano rises.

Geologists combined this with petrologic analyses of rock samples retrieved from the volcano, refining volume calculations and modelling based on these parameters.

"It has been proposed that hotspots that produce volcano chains like Hawai'i undergo progressive cooling over 1-2 million years and then die," Garcia said.

"However, we have learned from this study that hotspots can undergo pulses of melt production. A small pulse created the Midway cluster of now extinct volcanoes and another, much bigger one created Pūhāhonu. This will rewrite the textbooks on how mantle plumes work."

(Garcia et al., EPSL, 2020)

(Garcia et al., EPSL, 2020)

Pūhāhonu is a shield volcano, between 12.5 and 14.1 million years old, formed by a single magma plume surging through the mantle. Over the millennia, this source gradually built the volcano to a height of 4,500 metres (14,764 feet) from its lowest point, spanning an area 275 kilometres (171 miles) long and 90 kilometres (56 miles) wide.

Chemical analysis of rock collected from the volcano revealed a higher concentration of an olivine mineral called forsterite than we've ever seen in a Hawaiian volcano. This mineral indicates magma on the higher end of the temperature range.

The calcium oxide content in the forsterite allowed the team to infer the depth at which it formed, confirming that it did form in magma. Simulations allowed the team to calculate the pressure at which the forsterite formed, and the temperature.

According to these calculations, the magma clocked in at 1,703 degrees Celsius (3,097 degrees Fahrenheit) - hotter than any other Hawaiian basalt. This extreme temperature is reflected in the volcano's size, the researchers said.

It's an impressive beast in its own right. But it also has important implications for our understanding of the processes that create these incredible formations.

"The Hawaiian-Emperor Chain is arguably the world's best studied surface expression of a mantle plume," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"Nonetheless, new insights into its magmatic and thermal history continue to be revealed as more of the Hawaiian-Emperor Chain is mapped and sampled. These insights are providing a more complete understanding of the mechanics and thermal evolution of mantle plumes."

The research has been published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.