Did you know you have tiny tunnels in your head? That's OK, no one else did either until recently! But that's exactly what a team of medical researchers confirmed in mice and humans in 2018 – tiny channels that connect skull bone marrow to the lining of the brain.

The research shows they may provide a direct route for immune cells to rush from the marrow into the brain in the event of damage.

Previously, scientists had thought immune cells were transported via the bloodstream from other parts of the body to deal with brain inflammation following a stroke, injury, or brain disorder.

This discovery suggests these cells have had a shortcut all along.

The tiny tunnels were uncovered when a team of researchers set out to learn whether immune cells delivered to the brain following a stroke or meningitis originated from the skull, or the larger of the two bones in the shin – the tibia.

The specific immune cells they followed were neutrophils, the "first responders" of the immune squad. When something goes awry, these are among the first cells the body sends to the site to help mitigate whatever is causing the inflammation.

The team developed a technique to tag cells with fluorescent membrane dyes that act as cell trackers. They treated these cells with the dyes, and injected them into bone marrow sites in mice. Red-tagged cells were injected into the skull, and green-tagged cells into the tibia.

(Herrison et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2018)

(Herrison et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2018)

Once the cells had settled in, the researchers induced several models of acute inflammation, including stroke and chemically induced meningoencephalitis.

They found that the skull contributed significantly more neutrophils to the brain in the event of stroke and meningitis than the tibia. But that raised a new question – how were the neutrophils being delivered?

"We started examining the skull very carefully, looking at it from all angles, trying to figure out how neutrophils are getting to the brain," said Matthias Nahrendorf of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

"Unexpectedly, we discovered tiny channels that connected the marrow directly with the outer lining of the brain."

(Herrison et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2018)

(Herrison et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2018)

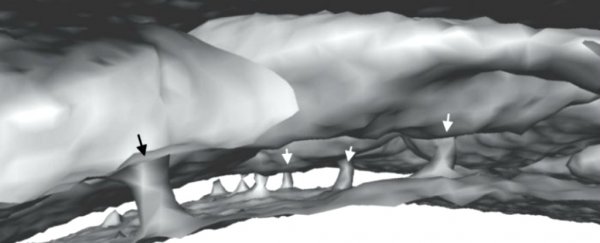

Using organ-bath microscopy – which uses a chamber full of solution to maintain the integrity of the isolated tissue while it is being examined – the team imaged the inner surface of a mouse's skull. There, they found microscopic vascular channels directly connecting the skull marrow with the dura, the protective membrane that encases the brain.

Normally, red blood cells flow through these channels from the interior of the skull to the bone marrow; but, in the case of stroke, they were mobilized to transport neutrophils in the opposite direction, from the marrow to the brain.

This was in mice, though. To find out if humans have something similar, the researchers obtained pieces of human skull from surgery and conducted detailed imaging.

They noticed channels there as well; five times larger in diameter than the channels in the mouse skulls, in both the inner and outer layers of bone.

Since the original discovery of these tiny tunnels, researchers have studied them more closely in mice, confirming in 2021 that the connection they form to bone marrow means the blood cells taking the trip aren't derived from the bloodstream, but are indeed produced directly from nearby marrow, making them highly localized and specific.

It's an amazing discovery, because inflammation plays a role in many brain disorders, and this could help scientists understand so much more about the mechanisms at play. It could also help understand conditions such as multiple sclerosis, wherein the immune system attacks the brain.

The original discovery was published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

A version of this article was first published in August 2018.