Just because Earth is the only place known to harbour life doesn't mean it's the best planet for the job.

Somewhere out there in the Universe, another orbiting object might be better positioned to support life, and it might not look like our own.

"We have to focus on certain planets that have the most promising conditions for complex life," says astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch from Washington State University.

"However, we have to be careful to not get stuck looking for a second Earth because there could be planets that might be more suitable for life than ours."

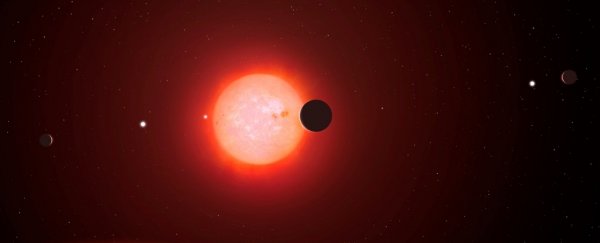

If we're too focused on finding another planet just like Earth, we might fail to notice one that is not only older, larger, warmer and wetter, but also orbits a star with a longer lifespan than our Sun.

Astronomers have been discussing the idea of a "superhabitable" planet for years, and now, we might have our first few candidates.

Among the thousands of exoplanets beyond our solar system, Schulze-Makuch and his colleagues have identified two dozen that appear to be more hospitable than Earth in at least one respect.

While none of these planets fulfil the full criteria for a superhabitable home, one of them does tick four key boxes, which suggests it might provide better and longer conditions for life than here on Earth.

Still, the point of the study is not to identify a planet B. Many of these planets are thousands of light-years away and haven't yet been statistically validated, which means they could turn out to be astrophysical false positives.

Even the planets that are confirmed are too far away to be practical destinations for further research. Especially when we've recently found potentially habitable exoplanets, similar to the size of Earth, just 124 light-years away.

"Our point here is not to identify potential targets for follow-up observations but to illustrate that superhabitable worlds may already be among the planets that have been detected," the authors write.

A larger planet than Earth, for instance, may allow for more habitable land and greater diversity. The size of a planet also impacts its gravitational pull, and a bigger one than Earth could retain its atmosphere for longer.

Water is of course a key component of life as we know it, and even in Earth's own history, we know that when there is greater humidity, life tends to thrive.

The Carboniferous period, which was warmer and wetter than today, produced so much biomass we are still harvesting coal, oil and natural gas from it today.

"It's sometimes difficult to convey this principle of superhabitable planets because we think we have the best planet," says Schulze-Makuch.

"We have a great number of complex and diverse lifeforms, and many that can survive in extreme environments. It is good to have adaptable life, but that doesn't mean that we have the best of everything."

One thing our planet doesn't have the best of is time.

It took roughly 3.5 billion years for macroscopic life to appear on Earth and in another 5 billion years or so, our Sun will burn out.

Other stars with masses similar to our own could run out of energy long before complex life develops, while those stars with lower masses, like orange dwarf stars, can last much longer.

Orange dwarf stars are somewhat cooler than those like our Sun, but they can sometimes burn for up to 70 billion years.

This astonishing amount of time may allow inhabited planets to build up higher biodiversity and more complex ecosystems than our own planet, which has only existed for roughly 4.5 billion years.

Of course, all of this is assuming that the life we are looking for out there is the same as what we know here on Earth. And that might not be the case at all. Still, we have to work with something, and in this case, Earth is the only example we have.

Among the 24 superhabitable candidates, astronomers say they identified 9 orbiting around K stars, 16 planets between 5 and 8 billion years old - deemed the sweet spot for complex life - and 5 planets in the optimal temperature range for a superhabitable planet, roughly 19°C.

All of these exoplanets were located in the habitable zone around their star, the region where water could exist.

Only one of the candidates fit all four criteria - an exoplanet called KOI 5715.01 about 1.8 times larger than Earth and located roughly 3,000 light years away.

That may not seem like much, but in the search for life outside our solar system, the authors think the possibility of a superhabitable planet with conditions even better than our own "may deserve higher priority for follow-up observations than most Earth-like planets."

"With the next space telescopes coming up, we will get more information, so it is important to select some targets," says Schulze-Makuch.

Not all of them need to resemble our own planet.

The study was published in Astrobiology.