Finding a potentially habitable exoplanet isn't as easy as you might think. Orbiting at a temperate distance from the host star is just the first step. Size and composition also play a role - as does the level of flare activity in the star. And all of that doesn't mean much if the system is so far away we can't take detailed observations to find out if it is habitable.

A newly discovered system looks like it could tick a good number of those boxes. And it's incredibly close - just 10.7 light-years away from the Solar System. This means it could soon become one of the most studied systems in our local neighbourhood.

"These planets will provide the best possibilities for more detailed studies, including the search for life outside our Solar System," said astrophysicist Sandra Jeffers of the University of Göttingen in Germany.

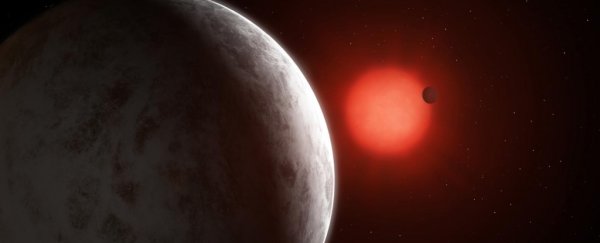

The star is called Lacaille 9352, or GJ 887. In its orbit, scientists have found two exoplanets that could be terrestrial - rocky, like Earth and Mars.Tantalisingly, there's also a hint of a third terrestrial exoplanet orbiting at a greater distance - a distance that could make it temperate, neither too hot nor too cold to prohibit liquid water on the surface.

This hint of the third planet is considered inconclusive at this stage, but the discovery of the two close-orbit planets (and the potential for the third planet) are enough to warrant a much closer look at the GJ 887 system.

The star itself, which is about half the mass of the Sun, is a red dwarf - a type of long-lived, relatively cool, small star - which is the most common type of star in the Milky Way.

We've found a lot of exoplanets orbiting red dwarfs; and, because these stars are not as hot as stars like the Sun, the habitable temperate zone for orbiting planets is a lot closer than it is for Earth.

The problem with red dwarfs, however, is that they're often rather rowdy, spitting out intense stellar radiation and flares that would render many of these close planets uninhabitable, by stripping their atmospheres.

This is where GJ 887 stands out. For a red dwarf, it's actually incredibly tranquil - it has very low starspot activity, and its brightness remains more or less uniform. This makes it of great interest to astronomers with the Red Dots survey - a project to search for terrestrial worlds around nearby red dwarf stars.

As part of this survey, the star was studied for three months using the European Southern Observatory's High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher instrument at the La Silla 3.6 metre telescope in Chile.

This sensitive instrument stares at stars, looking for the very slight changes in their light as they move just a tiny bit, tugged about by the gravitational influence of planets in orbit around them. In GJ 887, these movements revealed two distinct periodic signals.

The amount the star moves can be used to calculate the mass of the objects doing the tugging. This is how the researchers discovered the two exoplanets, GJ 887b and GJ 887c, confirmed by matching it up with 200 days of archival data obtained from 2002 to 2004.

GJ 887b has a minimum mass of around 4.2 times the mass of Earth, and it orbits the star once every 9.3 days. GJ 887c has a minimum mass of around 7.6 times the mass of Earth, and orbits the star once every 21.8 days.

Those masses put the exoplanets in the 'super-Earth' category, but without further study, it's impossible to tell if they're terrestrial or gaseous. At their respective proximities to the star, the two planets are unlikely to be habitable, but they're very close to the inner edge of the habitable zone.

The third signal, however - if it turns out to represent an exoplanet - would constitute an 8.3 Earth-mass super-Earth right in the middle of the star's habitable zone, with an orbital period of 50.7 days. There's just one problem - the signal was only detected once in the HARPS data.

This suggests that there might not be an exoplanet there at all. "We regard the third signal at ~50 days as dubious and likely related to stellar activity," the researchers wrote in their paper, but the possibility cannot be ruled out with the current data.

That means researchers will be going back for another look, to see if that signal can be picked up again, and planetary scientists will also want to take closer looks at GJ 887b and GJ 887c anyway.

Because of the lack of flare activity from the star, the two exoplanets may have retained their atmospheres, and because the light from the star is so steady, those atmospheres could be detectable as light from the star bounces off them.

Our current instruments aren't yet capable of measuring this, but it's one of the tasks the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for launch next year, has been built to perform. It will be sensitive enough to directly image nearby exoplanets, which should revolutionise the field of planetary science.

"These types of observations could tell us about the atmospheric makeup of these planets," astronomer Melvyn Davies of Lund Observatory in Sweden, who was not involved in the research, explains an article accompanying the paper.

"If further observations confirm the presence of the third planet in the habitable zone, then GJ 887 could become one of the most studied planetary systems in the Solar neighbourhood."

The research has been published in Science.