If you live in the Southern Hemisphere, next time you get the opportunity, go outside and look at the night sky. Most of that celestial plain is covered in a star cluster that's been torn apart by galactic tidal forces, and is now flowing past us as a giant river of over 4,000 stars.

Although it may be in plain sight, it's only just been discovered, revealed by the Gaia data that facilitated the most accurate 3D-map of the galaxy yet.

What makes this stellar stream exciting is its proximity to Earth. It's just 100 parsecs (326 light-years) away, offering an unprecedented opportunity to peer into the dynamics of a disrupted cluster.

"Identifying nearby disc streams is like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. Astronomers have been looking at, and through, this new stream for a long time, as it covers most of the night sky, but only now realise it is there, and it is huge, and shockingly close to the Sun," said astrophysicist João Alves of the University of Vienna.

"Finding things close to home is very useful, it means they are not too faint nor too blurred for further detailed exploration, as astronomers dream."

Stars tend to form in clusters in stellar nurseries, but they don't usually stay clustered for long - maybe up to a few hundred thousand years. It takes a lot of mass to build up enough gravity to hold a cluster together - even small galaxies orbiting the Milky Way can be torn apart by its tidal forces and end up stretched out into long rivers of stars orbiting the galactic core.

These can be hard to see, as Alves said, because we need quite a bit of information to be able to link the stars to each other. But this is what Gaia provided. Not only has it given accurate locations in 3D space for stars, it has given us their velocities, and excited astronomers have been using this data to identify stellar streams.

So when University of Vienna astronomers noticed a group of stars moving together, they took a closer look. They found the group bore the signatures of a stellar cluster that had been torn apart, and was now a stellar stream.

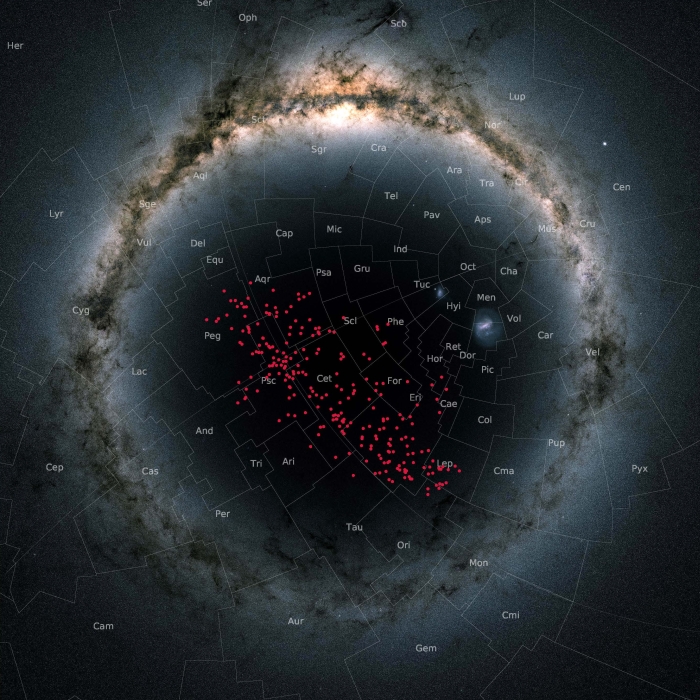

The river of stars in the southern sky. (Gaia DR2 skymap)

The river of stars in the southern sky. (Gaia DR2 skymap)

Due to Gaia sensitivity limitations, they were only able to analyse 200 stars in detail, but based on the interactions between the stars, the team extrapolated that the stream should contain at least 4,000 stars.

This star river is sizeable, about 200 parsecs (652 light-years) wide and 400 parsecs (1,305 light-years) long. These dimensions also help estimate its age.

The stream, the team argue, is not dissimilar to the open cluster the Hyades. At around 625 million years old, the Hyades is showing evidence of a tidal tail; it's in the early stages of being disrupted.

Hence, the researchers think this stream is older than the Hyades. Based on this comparison, and a set of stellar isochrone data (used to calculate the age of stars), the team has put the age of the stream at about 1 billion years.

That means it's completed around four full orbits of the Milky Way (the Sun takes about 230 million years to orbit the galactic core), which is sufficient time for it have stretched out into its attenuated shape.

"As soon as we investigated this particular group of stars in more detail, we knew that we had found what we were looking for: A coeval, stream-like structure, stretching for hundreds of parsecs across a third of the entire sky," said astronomer Verena Fürnkranz.

Most Milky Way stellar streams identified to date are actually orbiting outside the galactic disc, and are much larger - but this stream's location inside the disc could make it a valuable tool. For example, it could be used to help constrain the Milky Way's mass distribution.

It could also help shed light on how galaxies get stars, and test the Milky Way's gravitational field, the researchers said.

With the help of the Gaia data, they plan to look for more such streams in the night sky, hiding in plain sight.

The team's research has been published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.