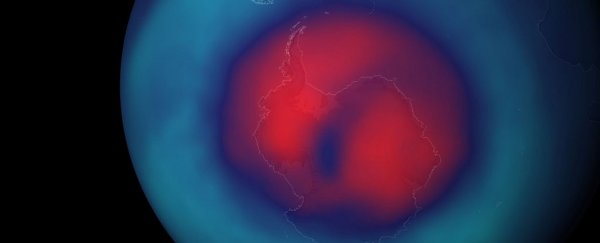

The surface area of the Antarctic ozone hole has been abnormally large for this time of year, breaking records in terms of its size for most of October. But scientists say there's no cause for alarm, as the expansion is expected to be temporary in nature due to seasonal fluctuations.

Researchers from the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), the official weather and climate agency of the United Nations, announced the news of the atypically large ozone hole this week, which reached its maximum extent on October 2 with an area of 28.2 million km2.

That's the biggest the ozone hole has ever been on that specific date, and the record-setting sizes for October dates kept pace throughout the month. Although, when averaged out for 30 consecutive days, it's not the largest the hole has ever been – with its average size of 26.9 million km2 trailing behind the record sizes observed in 2000 (29.8 million km2) and 2006 (29.6 million km2).

Nonetheless, the fact that the ozone hole is still capable of creating record-setting sizes is proof that the ozone issue remains a pressing environmental situation, despite evidence that a projected long-term recovery is now underway.

"This shows us that the ozone hole problem is still with us and we need to remain vigilant," said Geir Braathen, a senior scientist in WMO's Atmospheric and Environment Research Division. "But there is no reason for undue alarm."

Last year, scientists announced that the ozone hole was showing the first signs of healing after decades of expansion due to ozone depletion. Human-caused ozone depletion, occurring in the stratospheric ozone layer at an altitude of approximately 25 kilometres, is thought to have taken place for decades due to the use of damaging chemicals before the problem was identified in the 1970s and '80s.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer banned the use of harmful chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and is credited with restoring ozone to the stratosphere – most notably in the hole over Antarctica – although it's worth noting that it took decades for scientists to observe any progress being made against the depletion.

"The Montreal Protocol is in place and is working well," said Braathen. "But we may continue to see large Antarctic ozone holes until about 2025 because of weather conditions in the stratosphere and because ozone-depleting chemicals linger in the atmosphere for several decades after they have been phased out."

It's expected that the general ozone layer will make a substantial recovery by midway through the century, with the Antarctic ozone hole estimated to recover by about 2070.

In the meantime, however, we may still see fluctuations in the size of the hole – especially during spring in the Southern Hemisphere, when extremely cold temperatures in the stratosphere and heightened levels of sunshine lead to a natural release of ozone-destroying chlorine and bromine.