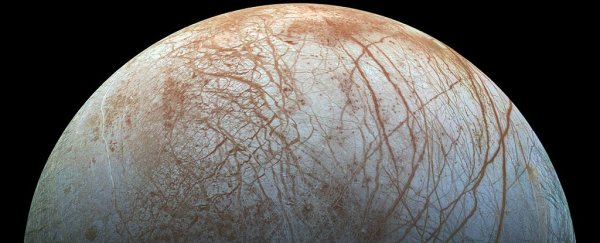

Europa, a moon of Jupiter thought to harbor a warm, saltwater ocean sloshing beneath a thick, icy crust, has long been considered one of the best spots in the Solar System to look for alien beings.

Now, citing data collected by NASA's Galileo probe more than two decades ago, scientists report that giant jets of water are spouting more than 100 miles off that moon's surface. The study, published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy, adds to the mounting evidence that Europa is spewing its contents into space.

If the existence of the plumes is confirmed and they are linked to Europa's ocean, they could provide a tantalizingly straightforward way to sample the moon in search of signs of life.

Rather than land on the surface and drill as much as 15 miles through ice - a feat that has never been achieved even on Earth - a spacecraft could simply fly through the spray and test its contents.

Researchers are already working on missions to do just that. NASA's Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) are slated to launch in the early to mid-2020s, both armed with high-resolution cameras and a suite of other sensitive instruments.

"The idea that Europa might possess plumes seems to be becoming more and more real, and that's very good news for future exploration," said Xianzhe Jia, a space physicist at the University of Michigan and the lead author of the new paper on the phenomenon.

The results of the Clipper and JUICE missions, he continued, "could have huge implications" - nudging us Earthlings closer to understanding whether we are alone.

Scientists have suspected since 2012 that Europa might harbor plumes, after the Hubble Space Telescope observed water vapor spouting above the moon's frigid south pole.

Another set of observations, taken in 2014 and 2016, found a recurring jet shooting from an unusually warm "hot spot" near the moon's equator.

The tallest of the plumes was so powerful that it extended 120 miles (193 km) above the moon's surface; Old Faithful, the famous geyser at Yellowstone, reaches 184 feet (56 metres).

The interpretation of those images has been debated; the images pushed the limits of Hubble's sensitivity, and sometimes the space telescope was unable to spot the plumes altogether.

The ongoing debate called for on-site observations, Jia said. But no spacecraft has gotten close to Europa since Galileo, which swooped 250 miles 400 km) above the moon's "hot spot" in December 1997.

That mission had a severe shortcoming: The spacecraft's more powerful antenna failed to deploy after launch, limiting the amount of data the spacecraft could send back to Earth.

Nevertheless, Jia - who was a college student during the flyby - thought that if a plume existed, Galileo might have sensed its signatures with its magnetometer and plasma wave instruments.

Margaret Kivelson, a space physicist at the University of California at Los Angeles who was principal investigator for Galileo's magnetometer, confirmed his hunch.

"On one particular pass, the spacecraft came very, very close to the surface of Europa, and it was on that pass that we saw signatures that we never really understood," she said at a news conference Monday.

Galileo found Europa's magnetic field intensified and shifted orientation just as the spacecraft made its closest approach to the moon. Then, data from the plasma wave instrument showed unusual emissions that could be associated with a high density of charged particles.

The results didn't make sense at the time - but they are just what scientists would expect to find near a speeding jet of salty water.

But the environment around the moon is complex - warped by Jupiter's strong magnetic fields and by Europa's atmosphere.

So Jia, Kivelson and their colleagues ran the data through a sophisticated modeling program that compared the observations with what scientists might expect to see from a plume of the dimensions reported by Hubble. The results were in "satisfying agreement," Jia said.

Kivelson, who hadn't considered such a plume when she collected the data two decades ago, marveled at the new discovery. "It's amazing how hard it is to anticipate something that just hasn't happened before," she said.

The source of the plume is still unclear. The prevailing theory is the water comes directly from Europa's subsurface ocean and is being driven upward by hydrothermal activity much like that which powers geysers on Earth.

But the water could originate elsewhere, Jia cautioned. Some have suggested that there might be a subsurface lake hiding between layers of Europa's thick ice sheets.

The behavior of the plumes is also unpredictable. Because they were initially seen when Europa was farthest from Jupiter, researchers thought they might be driven by tidal stress - the friction generated by Jupiter's gravitational pull that keeps Europa's interior liquid.

But follow-up observations from Hubble were unable to confirm that idea.

Jia hopes this paper will inspire fellow researchers to keep looking at Europa's plumes. Perhaps someone else will find further clues by mining years-old data.

Or, maybe when the powerful James Webb Space Telescope finally launches (it has been pushed back several times), it will get a clearer picture of what is happening on the alien moon.

The Clipper mission - now in the preliminary design phase - is projected to arrive at Jupiter sometime around 2030. There it will perform 45 flybys past Europa, getting as close as 16 miles above the moon's surface.

If it finds a plume, Clipper's instruments will be able measure its chemical composition, said Elizabeth Turtle, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and one of the primary researchers involved with the mission.

The spacecraft will seek molecules associated with biological activity.

"But it's a long stretch to go from being able to measure the specific composition to being able to say, 'There's life'," she cautioned at the news conference Monday.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.