Curiosity affects everything from our relationships to our education, but it's not easy to pin down and put under a microscope to study. With the help of Wikipedia though, researchers have now done just, exploring two main types of curiosity.

Using Wikipedia browsing as an activity to observe, and a maths technique called graph theory to formally chart and measure it, 149 participants were observed browsing for 15 minutes a day over the course of 21 days, covering 18,654 pages in total.

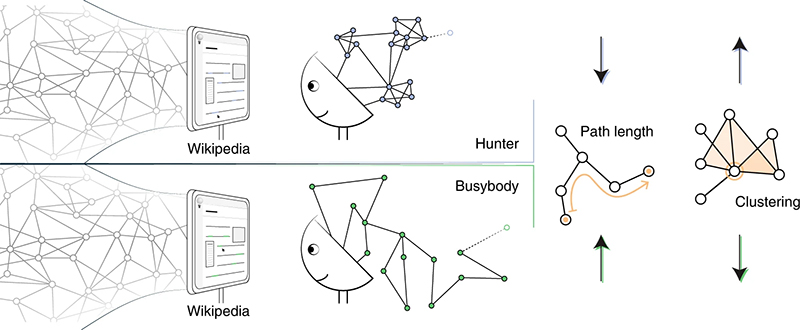

The resulting study was able to split the individuals into two previously identified types, as far as curiosity goes: the 'busybody' who explores a lot of diverse information, and the 'hunter' who stays on a more focused track when it comes to gaining knowledge.

Wikipedia browsing behaviour was used to analyse curiosity. (Lydon-Staley et al, Nature Human Behaviour 2021)

Wikipedia browsing behaviour was used to analyse curiosity. (Lydon-Staley et al, Nature Human Behaviour 2021)

"Wikipedia allowed both introverts and extroverts to have equal opportunity in curious practice, a limitation in other studies of curiosity, while the ad-free search engine allowed individuals to truly be captains of their own curiosity ships," says biophysicist Danielle Bassett, from the University of Pennsylvania.

By recording pages as nodes and analysing how closely they were related, Bassett and her colleagues were able to find both busybodies and hunters in their pool of volunteers – those who tended to jump all around Wikipedia and those who were more likely to stay on closely related pages.

However, the participants didn't always stick to one type of behaviour or the other, and the researchers wanted to find out why. To do this, they used a wellbeing questionnaire given to the participants before the study began, covering topics like seeking out social interaction and tolerating stress.

Based on the surveys, a need to fill specific knowledge gaps seemed to drive hunter-style behaviour, while a desire to seek out brand new information was an indicator of a busybody-style of Wikipedia browsing – taking larger leaps between nodes or pages.

"We hypothesise that a switch from hunter to busybody style might arise due to sensation seeking, or the craving for novelty and new information during the day," says Bassett.

One of the reasons that this study stands out is that it looks at how curiosity is expressed – rather than trying to quantify it through engagement in activities like asking questions, playing trivia games, and gossiping, as previous studies have done.

These findings can be useful in a number of ways, including in informing approaches to teaching – particularly in how knowledge and resources can be best presented, and how different problem-solving styles can be supported.

Curiosity is also linked to emotional wellbeing: people who are more curious tend to be more satisfied with life and less anxious. By making sure information is available in ways that are accessible, we can foster curiosity and promote contentment at the same time.

"We need more data to know how to use this information in the classroom, but I hope it discourages the idea that there are curious and incurious people," says psychologist David Lydon-Staley, from the University of Pennsylvania.

The research has been published in Nature Human Behaviour.