Earth's largest remaining tract of tropical rainforest is kept alive by a complex water cycle that we're only just beginning to understand. Yet our activities are changing it before we can see the full picture, a new report finds.

The rivers and tributaries of the Amazon rainforest hold around a fifth of Earth's fresh water, nourishing a stunning variety of mammals, birds, plants and amphibians. It also helps support the 47 million people in the surrounding basin region which includes mountain forests, wetlands, and river systems across nine South American countries.

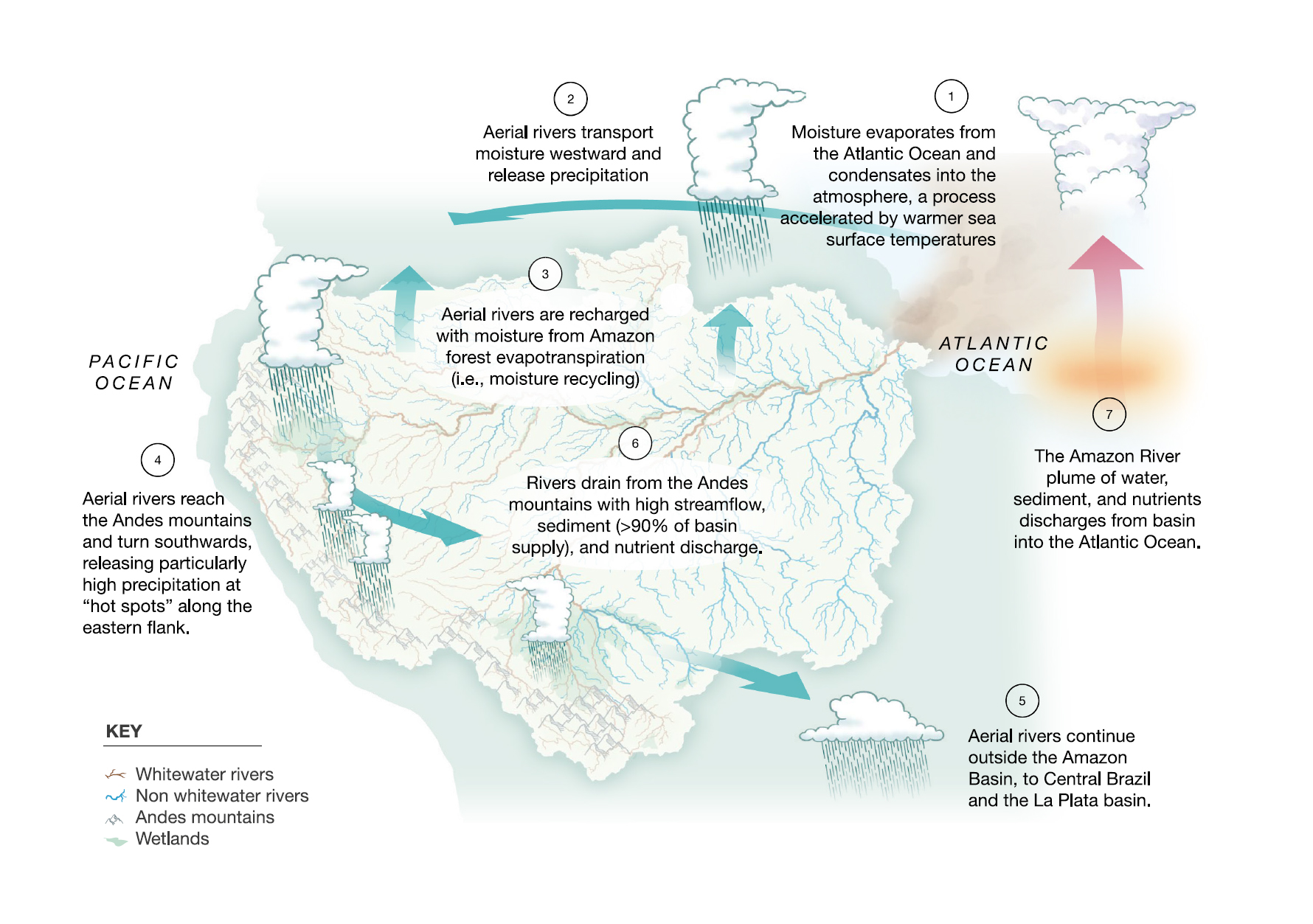

The complex hydroclimatic system that sustains this region interconnects over the Andes mountains, Amazon lowlands and Atlantic Ocean (the AAA pathway), cycling water molecules from Earth's surface into the air and back again. Researchers have previously compared this system to a pump that recycles moisture, supporting regional rainfall.

"Up to now, most research and conservation efforts have focused on the terrestrial rainforest biome, yet rainforest persistence hinges on the AAA pathway," Florida International University hydrologist Claire Beveridge and colleagues point out in their review.

This multidirectional water cycle not only supplies the rain but shifts soils too – from the Andes mountains, through the rivers, into the forests, and eventually into the ocean. These waves of nutrients washing through with the water help support the densely packed and highly diverse terrestrial and aquatic habitats.

The AAA pathway provides about 40 percent of the Atlantic's sediment input, contributing to many ocean nutrient cycles.

"The Amazon River plume extends several thousands of kilometers into the Atlantic Ocean, and its composition makes it vital to ocean nutrient balance and carbon dioxide sequestration," the researchers write.

While the Amazon has always gone through cycles of floods and droughts thanks to the natural El Niño and La Niña climate patterns, these cycles no longer fully account for all the changes being observed.

Temperatures are rising, particularly in the south of the region, causing the AAA system to fluctuate more extremely. This has brought record floods to the north and lengthened dry spells and fire seasons, raising the risk of glaciers melting in the Andes.

Deforestation and other land cover changes are also influencing the AAA system and exacerbating climate change in a dangerous feedback loop.

"The combined changes along the AAA pathway and their cumulative impacts are occurring at faster speeds than social–ecological systems can adapt, threatening their resilience," warn Beveridge and team.

The researchers urge for further investigation into the AAA pathway, an immediate stop to deforestation, and restoration programs to repair vulnerable areas. Keeping the Amazon Basin wet is also crucial for global efforts to mitigate climate change.

"In this century, there's been a huge increase in the number and extent of protected areas like national parks, reserves and Indigenous territories that are recognized officially in the Amazon, but the focus has really been on forests and terrestrial ecosystems," says FIU freshwater scientist Anderson.

"It's now time to extend support for conservation to freshwater systems like rivers."

This research was published in PNAS.