Tiny fragments of microplastics are making their way deep inside our bodies in concerning quantities, significantly through our food and drink.

Scientists have recently found a simple and effective means of removing them from water.

A team from Guangzhou Medical University and Jinan University in China ran tests on both soft water and hard tap water (which is richer in minerals).

"Tap water nano/microplastics (NMPs) escaping from centralized water treatment systems are of increasing global concern, because they pose potential health risk to humans via water consumption," write the researchers in their paper, published in February.

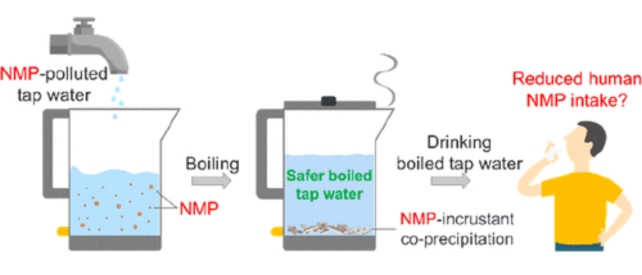

They added in nanoplastics and microplastics before boiling the liquid and then filtering out any precipitates.

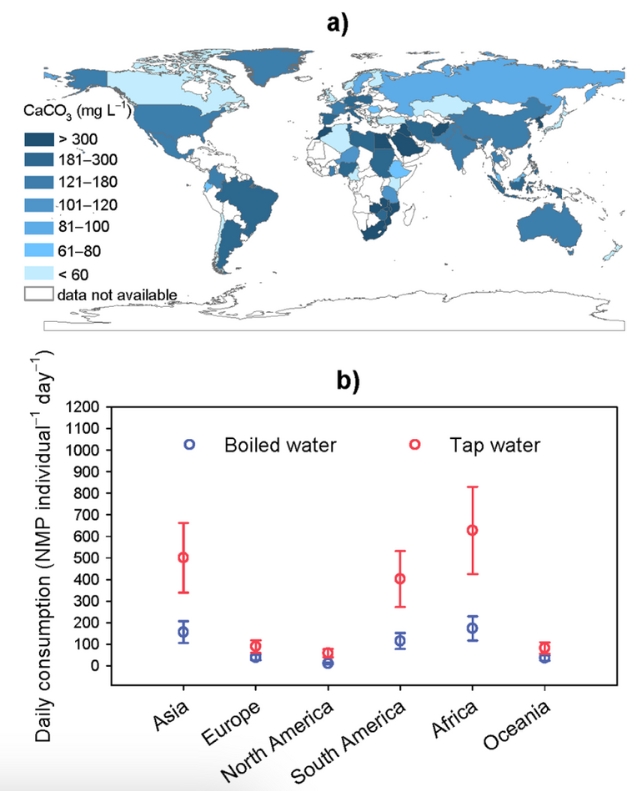

In some cases, up to 90 percent of the NMPs were removed by the boiling and filtering process, though the effectiveness varied based on the type of water.

Of course the big benefit is that most people can do it using what they already have in their kitchen.

"This simple boiling water strategy can 'decontaminate' NMPs from household tap water and has the potential for harmlessly alleviating human intake of NMPs through water consumption," write biomedical engineer Zimin Yu from Guangzhou Medical University and colleagues.

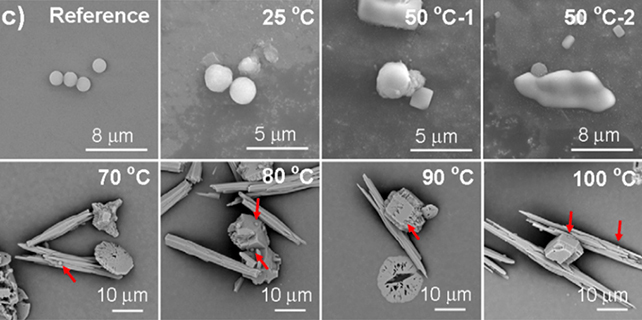

A greater concentration of NMPs was removed from samples of hard tap water, which naturally forms a build-up of limescale (or calcium carbonate) as it is heated.

Commonly seen inside kitchen kettles, the chalky substance forms on the plastic's surface as changes in temperature force the calcium carbonate out of solution, effectively trapping the plastic fragments in a crust.

"Our results showed that nanoplastic precipitation efficiency increased with increasing water hardness upon boiling," the team writes.

"For example, from 34 percent at 80 mg L−1 to 84 percent and 90 percent at 180 and 300 mg L−1 of calcium carbonate, respectively."

Even in soft water, where less calcium carbonate is dissolved, roughly a quarter of the NMPs were snagged from the water.

Any bits of lime-encrusted plastic could then be removed through a simple filter like the stainless steel mesh used to strain tea, the researchers say.

Past studies have measured fragments of polystyrene, polyethylene, polypropylene, and polyethylene terephthalate in potable tap water, which we're consuming daily in varying quantities.

To put the strategy to the ultimate test, the researchers added even more nanoplastic particles, which were effectively reduced in number.

"Drinking boiled water apparently is a viable long-term strategy for reducing global exposure to NMPs," write the researchers.

"Drinking boiled water, however, is often regarded as a local tradition and prevails only in a few regions."

The research team hopes that drinking boiled water might become a more widespread practice as plastics continue to take over the world.

While it's still not certain exactly how damaging this plastic is to our bodies, it's clearly not the healthiest of snacks.

Plastics have already been linked to changes in the gut microbiome and the body's antibiotic resistance.

The team behind this latest study wants to see more research into how boiled water could keep artificial materials out of our bodies – and perhaps counter some of the alarming effects of microplastics that are emerging.

"Our results have ratified a highly feasible strategy to reduce human NMP exposure and established the foundation for further investigations with a much larger number of samples," write the authors.

The research has been published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

An earlier version of this article was published in March 2024.