Ancient sheep buried in an elite grave in Egypt show the oldest evidence of humans deliberately deforming the horns of livestock. Exactly why it was done remains a mystery.

In the 5,700-year-old dig site of Hierakonpolis, Upper Egypt, archaeologists uncovered the remains of five male sheep that showed clear evidence of having their horns artificially modified.

This has long been practiced on cattle in Africa, even today, but this marks the oldest direct physical evidence for it, as well as the first time it's been seen in sheep in Africa.

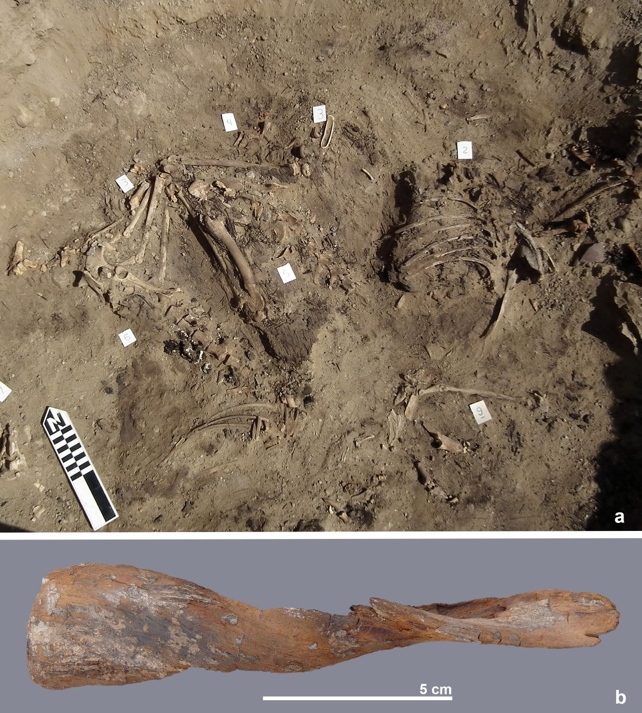

The specimens belong to an extinct variety of sheep with corkscrew-shaped horns, which naturally grew sideways out of the animals' heads. But of the remains in these tombs, three sheep had had their horns modified to point straight up.

The horns of another weren't quite as straight but still closer together than usual, indicating some attempts at deformation. The horns of the fifth animal had been completely removed, while a sixth sported au naturel horns.

"Notches in the horns suggest that the ancient Egyptians used ropes to bind them together," says Bea De Cupere, archaeozoologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

"Holes in the skull bones indicate that herders also broke the skull of the young animals to force the horns to grow upright. It is a practice that certain African pastoral communities still apply to cattle."

Why the ancient Egyptians might have performed this procedure is still unclear, but the researchers speculate that it could have been ritualistic, or perhaps a kind of display of power over nature.

As far back as 3700 BCE – a millennium before the pyramids were built – Hierakonpolis was a major city in Upper Egypt. The archaeological site features graves of both common people and elites, as well as a surprising variety of animals, suggesting it was home to the oldest known example of what we might call a zoo.

Judging by remains found so far, that menagerie included local and imported wildlife like hippos, crocodiles, elephants, baboons, wildcats, and aurochs, as well as domestic animals like cats, dogs, cows, and of course sheep.

While sheep remains have been found all through Hierakonpolis, those with modified horns were only found in the elite cemetery.

That wasn't the only difference either: dentition and bone fusing examinations showed that these sheep were much older and larger than other sheep used for food. Castration can explain this, and would have also had the benefit of making the animals more docile.

Making the elite sheep look more impressive than those kept by common people could be the whole point, the team suggests.

"The elite wanted to display their power by keeping wild and exotic animals, and perhaps also by straightening the horns of impressively large sheep," says archaeozoologist Wim Van Neer.

"Maybe they wanted the sheep to look like addaxes from the Sahara? Or perhaps the animals were involved in rituals? For now, we can only speculate."

Whatever the reason, this is not only the first time the practice has been found in sheep, but at an age of around 5,700 years, these sheep earn the honor of the earliest known example of deliberate livestock horn deformation. The previous oldest comes from cattle in a site in Sudan, which dates back at least 4,000 years ago.

Further studies could help reveal why and how the ancient Egyptians deformed the horns of animals, and could even fill in the gaps for how and when these corkscrew-horned sheep declined as the more crescent-horned 'ammon' sheep took their place.

The research was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.