It's not only the community of tiny microbes that live on your tongue that give us unique tongue-prints, but the tongue's own surface structures as well.

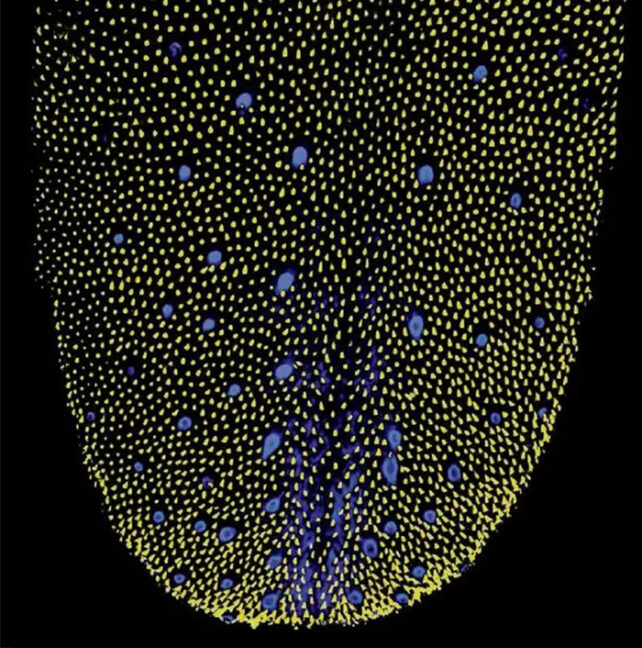

Our taste and touch buds arrange themselves into unique patterns of sizes and positions, providing each of us with a distinct sense of touch and flavor preferences too. Just a single one of these buds, called papillae, can be used to identify someone in a small group with an accuracy of 48 percent, researchers discovered.

"We were surprised to see how unique these micron-sized features are to each individual," explains University of Edinburgh data scientist Rik Sakar.

"Imagine being able to design personalized food customized to the conditions of specific people and vulnerable populations and thus ensure they can get proper nutrition whilst enjoying their food."

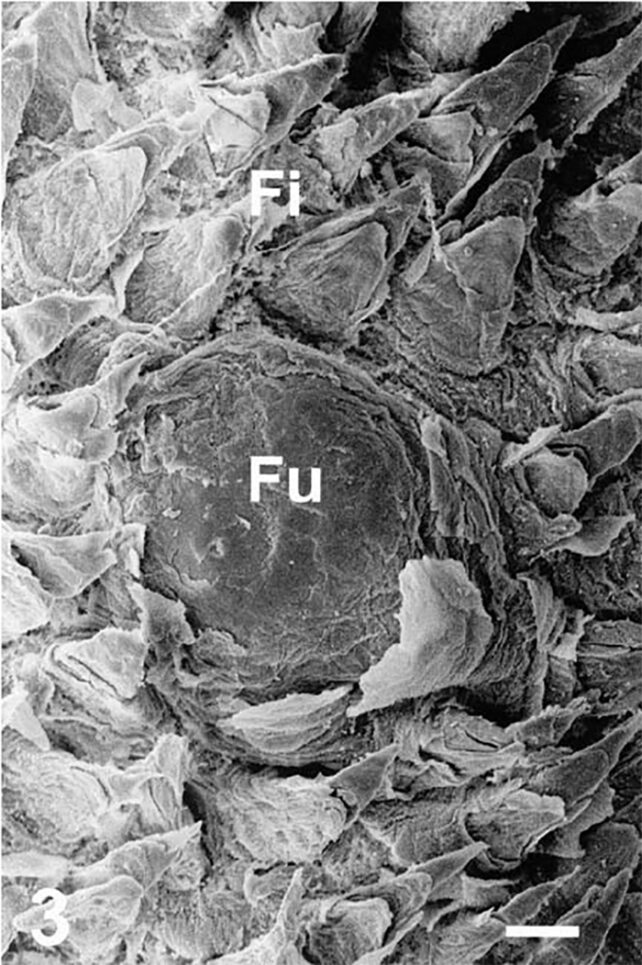

Our tongues are complicated organs. Among the tiny bumps on its surface are structures called fungiform papillae, which contain the taste buds that allow us to detect when something is sweet, sour, or something else. Every square centimeter of our tongues contain up to 200 of these taste-packets.

Then there are the filiform papillae. Lacking taste receptors, they detect the textures food through touch. These papillae are capable of measuring friction and lubrication, which can vary with the presence of saliva so play a part in informing our brains on our level of hunger.

Using 3D microscopic scans of over 2,000 human papillae from 15 people, a trained AI tool sorted out which shapes corresponded to which type: taste or touch.

Mapping the shapes and position of the papillae, the program could identify the type of papilla with 85 percent accuracy. It could also identify which of the 15 participants a single papilla belonged to almost half of the time.

"It was remarkable that the features based on topology worked so well for most types of analysis, and they were the most distinctive across individuals," says data scientist Rayna Andreeva from the University of Edinburgh.

They also found the women and younger people in their group tended to have pointier papillae.

"In past research, women and younger people have been noted to have higher density of fungiform papillae, which has been attributed to variations in taste perception, and women have been observed to be supertasters more frequently," Andreeva and team write in their paper.

However, with only 15 individuals for the AI to choose from, larger studies are still needed to confirm the trends seen in this research.

"This study brings us closer to understanding the complex architecture of tongue surfaces," Saker concludes.

"We are now planning to use this technique combining AI with geometry and topology to identify micron-sized features in other biological surfaces. This can help in early detection and diagnosis of unusual growths in human tissues."

This research was published in Scientific Reports.