Scientists have found what they think is the oldest animal footprint in the fossil record, uncovering incredibly ancient track marks imprinted in the dirt as far back as 550 million years ago.

These trackways, preserved near burrows, were discovered in Dengying Formation – a rich fossil preserve in China's south – and constitute the first evidence confirming that an ancient group of animals called bilateria actually pre-dates the Cambrian explosion.

This 'explosion' – which ignited some 541 million years ago – saw the rapid emergence of a diversified spread of animal phyla over a period lasting perhaps 25 million years.

Prior to this, animal life on Earth consisted of simpler, single-celled or multicellular organisms, but the Cambrian Period gave rise to more complex creatures of a kind we recognise today, including bilaterian animals, who exhibited the first bilateral symmetry.

This nifty piece of evolution gave them things like heads, tails, bellies, and backs – not to mention something else that's incredibly useful: legs.

"Animals use their appendages to move around, to build their homes, to fight, to feed, and sometimes to help mate," one of the researchers, geobiologist Shuhai Xiao from Virginia Tech University, told The Guardian.

"It is important to know when the first appendages appeared, and in what animals, because this can tell us when and how animals began to change to the Earth in a particular way."

While bilaterian animals – including arthropods and annelids – were suspected to have first stretched their innovative legs prior to the Cambrian explosion, in what's called the Ediacaran Period, before now there was no evidence for it in the fossil record.

That's why these Dengying track marks are a big deal for our understanding of evolutionary history – one small step for a bilaterian perhaps, but one giant leap for animal kind.

In a sense, it's amazing the researchers were able to find anything at all.

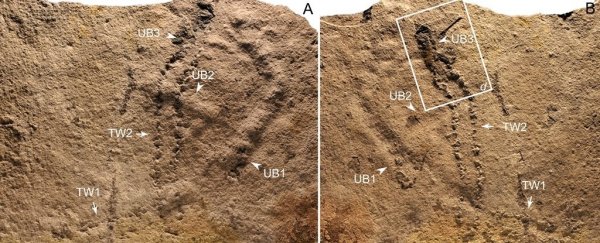

The 550-million-year-old tracks measure only a few millimetres in width, and consist of two rows of imprints arranged in what the researchers describe as a "poorly organised series or repeated groups", which could be due to variations in gait, pace, or interactions with the surface of what was once an ancient riverbed.

"The footprints are organised in two parallel rows, as expected if they were made by animals with paired appendages," Xiao told The Independent.

"Also, they are organised in repeated groups, as expected if the animal had multiple paired appendages."

In other words, this prehistoric critter wasn't a biped like you or me, but perhaps something with multiple paired legs – such as a spider, or a centipede – although given we have so little to go upon, the researchers emphasise it's impossible to know for sure what specific form this early walker embodied.

"We do not know exactly what animals made these footprints, other than that the animals must have been bilaterally symmetric because they had paired appendages," Xiao explains.

"Unless the animal died and [was] preserved next to its footprints, it is hard to say with confidence who made the footprints."

Still, due to the proximity of the track marks to fossilised burrows discovered nearby, the researchers hypothesise the creature may have exhibited "complex behaviour", such as periodically digging into sediments to mine oxygen and food among its riverbed habitat.

More than that, it's hard to say, but we know that this little thing walked when the world was young, and right now that's everything.

The findings are reported in Science Advances.